The Luftwaffe Relied on a Handful of Workhorses

|

| The Junkers Ju 52 was the Luftwaffe’s true workhorse. |

This article is intended as an introduction to

the workhorses of the Luftwaffe. I have written separate articles about them, so click on the links regarding each plane if you want to learn more about them. There were many other Luftwaffe planes, but this article is devoted only to the backbone of the Luftwaffe.

These were the workhorses in each of the major categories of every World War II air force: fighters, transport planes, ground-attack planes, and bombers. From them, I will choose the one true workhorse of the Luftwaffe.

There was only one or at most two workhorse aircraft for each of these broad aircraft categories. Generally, the same group of top Luftwaffe planes served throughout the conflict, though they were in a continual upgrade process. There were not a lot of successful designs that entirely replaced serviceable aircraft types during the conflict, though there were some new good designs that supplemented the workhorses. Among other reasons, this heavy reliance on only a few major aircraft types was due to the time and effort it would take to retool aircraft factories - time that the Third Reich did not have in abundance.

|

| The Bf 109 was the Luftwaffe's workhorse fighter. |

Fighters

Fighters are pretty much everyone's favorite class of aircraft. Which would you rather stand around an admire, a Maserati or a Gremlin? Each has their uses - Gremlins carried home an awful lot of groceries and Maseratis not so much - but faster and deadlier craft will always be more interesting than mundane and practical ones.

|

| A lineup of Focke-Wulf Fw 190s. |

The workhorse Luftwaffe fighter was the

Bf 109 (sometimes called the Me 109 or the "Messerschmidt"). It went through multiple revisions throughout the war, but the design definitely was beginning to show its limitations by 1945 (for example, it could remain in the air for only a little more than an hour while the

US P-51 could stay aloft for several hours). Designer Kurt Tank added his

Focke-Wulf Fw 190 during the summer of 1941, and it also went through numerous models. The top Luftwaffe pilots tended to prefer the Fw 190 after some initial skepticism. The Fw 190 was a big mystery plane to the Allies until a German pilot got confused and

landed one in perfect condition in England by mistake in June 1942.

|

| The Me 252 jet fighter caused the Allies a lot of problems. |

The excellent

Me 262 jet fighter came along in the fall of 1944 and was the preferred mount for the best pilots from that point on, but there weren’t enough of them to go around. Incidentally, one of the main reasons the Me 262 was so popular with the pilots was that it was very survivable - the Allies had great difficulty shooting them down until they figured out that they could just hang out near their airfields and catch them as they were slowing down to land.

|

| An FW-190 A5 fighter-bomber loaded with 1x500kg and 2x250kg bombs. |

One thing that many people overlook regarding both the Bf 109 and the Fw 190 is that they were good fighter-bombers. Once they dropped their bombs, they were ready to take on the best fighters the Allies could throw at them. The Luftwaffe really began to appreciate this capability as a means of drawing RAF fighter up to battle early in the war, and then also late in the war as their obsolete bombers became more and more vulnerable to Allied night fighters.

|

| A Junkers Ju 52. I like its appearance, it has a sort of art deco styling. |

Transport Aircraft

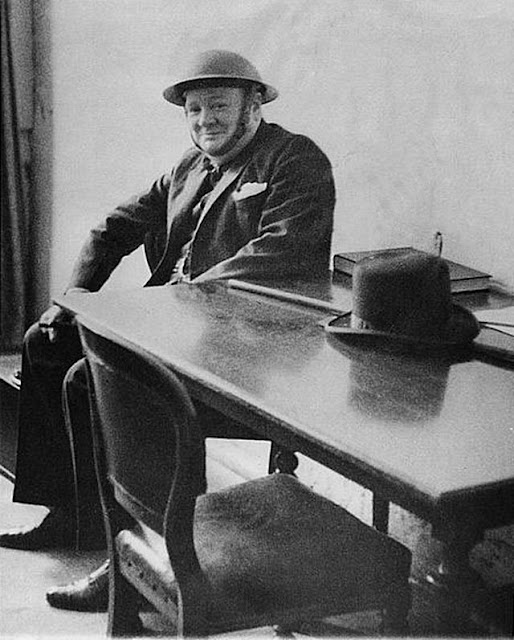

In terms of transport aircraft, the

Junkers Ju 52 was the Luftwaffe’s workhorse throughout the war years. It wasn’t that fast and didn’t have particularly good specifications or defensive armament, but the Ju 52 could fulfill a variety of necessary functions. The Ju 52 originally was designed as a seaplane, but it was the best aircraft to fill the gap in the Luftwaffe’s lineup for cargo planes, so it was adapted to land use.

|

| A swarm of Ju 52s bringing supplies and troops across the Black Sea to the troops marching on Stalingrad during the summer of 1942. |

The problem for the Luftwaffe was that Hitler kept creating situations where the Ju 52 had to fly over enemy territory and in airspace where it could not be adequately defended. It simply was not equipped to do that well. For instance, large numbers were lost during

the invasion of Crete, during the supply operations at Kholm and Demyansk, and then at

Stalingrad. If the Ju 52 could have just operated behind the front, it would have been available in abundance to do the types of transport jobs it was good at.

|

| The cockpit of the Junkers Ju 52 embodied classic styling. |

Hitler put his own stamp of approval on the Ju 52 by using one as his personal aircraft during the 1930s. Upon the outbreak of war, he switched to a

Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor because it was faster and thus less vulnerable to Allied fighters.

The Condor was the best reconnaissance plane in the Luftwaffe and sank a lot of Allied ships, some quite large. It also served as a transport, especially as the war ground on, but this did not maximize its capabilities. The Condor's chief advantage was its exceptional range of 3,560 km (2,210 mi, 1,920 nautical miles). Its payload was up to 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb) of bombs internally or up to 5,400 kg (11,900 lb) externally on four PVC 1006 underwing racks. However, only 276 Condors were built, and it did not have a very good defensive armament. The Luftwaffe made an early (and wise) decision to prohibit its use as a bomber in order to preserve its numbers.

|

| The Junkers Ju 252 was "better" than the Ju 52 but too fancy for the Luftwaffe's needs. |

The Luftwaffe developed an upgraded version of the Ju 52, the Ju 252, by mid-1941. However, it used too many strategic materials (rare metals) and also used engines that were in short supply (the Junkers Jumo 211F). So, very few of these were built and then back to the drawing board. A subsequent model that used fewer strategic materials and engines that were more plentiful, the Ju 352 "Hercules," was the final model. It was not as well-regarded as the Ju 252 but certainly had better capabilities than the original Ju 52. The Ju 352 even had a hydraulically powered

Trapoklappe (rear loading ramp) that facilitated the loading of heavy vehicles or freight whilst holding the fuselage level. It should be noted, however, that the Ju 352 could only carry smaller vehicles, not tanks. Only 43 of the Ju 352 model were built before the war situation required a halt to production.

|

| The Junkers Ju 352. Was it a better plane than the Ju 52? Absolutely. Was it available when the German war effort would have really benefited from it? Absolutely not. |

This progression of the Ju 52 shows a larger truth. Getting a serviceable design in operation at the right time is more important than building superior design later when it no longer matters. This is a trap that many students of the war fall into, thinking that just because some later design had better specifications, that meant it was the "best." A good design that comes along too late to matter is not the "best" in my opinion. The best design is one that you can use when it counts. The Ju 52 was the backbone of the Luftwaffe during the time of decision.

Ground-Attack Planes

While it is easy to dismiss ground-attack planes as boring and the old-age home for planes that didn't really make it in other roles, they were supremely important in the Wehrmacht. The German military always focused on the ground campaign to the exclusion of almost everything else, including the air war. This narrow focus paid a lot of dividends (superior army performance) and had serious drawbacks (failure to develop a strategic bomber). It resulted in a highly developed integration between the Army (

Heer) and the Luftwaffe. This was the essence of the famous "Blitzkrieg" advances and a source of Hitler's early victories.

|

| The Stuka of the cover of the February 1942 Der Adler military magazine wears an evil grin as it is loaded for action. |

As mentioned above, the Bf 109 and Fw 190 were useful as ground-attack planes. However, the workhorse in this area was the

Junkers Ju 87 Stuka. These were slow and ponderous and thus suffered the same faults as the Ju 52 transport planes. They were a liability when tasked with missions beyond their capabilities, most notably when used for bombing raids in airspace where the Allied held clear supremacy. Thus, they failed miserably during the Battle of Britain and large numbers were lost over Malta.

|

| A Stuka equipped with massive tank-busting cannons. |

However, the Ju 87G Stukas equipped with the massive two 37 mm (1.46 in) Bordkanone BK 3,7 cannons were outstanding tank-killers even if even slower and more ponderous than other variants. The most battle-hardened Luftwaffe pilots such as

Hans-Ulrich Rudel were using them to knock out Soviet tanks right up to the Battle of Berlin. This is an example of where a plane that is not particularly good at many things is an outstanding contributor to the military effort because it does one thing exceedingly well.

|

| A Heinkel He 111 shot down in England during the Battle of Britain. |

Bombers

The Germans never really had a workhorse bomber, which was the Luftwaffe’s major failing. They tried all sorts of different medium bombers with mediocre results for each of them. These included the Junkers Ju 88, which was probably the best of a bad lot. Others which were almost all obsolete by the middle of the conflict included the Heinkel He 111, the Dornier Do 17, and the Heinkel He 177 Greif (Griffin). The Griffin was so prone to engine fires that the pilots took to calling it the “flying fireworks.”

|

| The Arado Ar 234 - too little, too late. |

The

Arado Ar 234 Blitz Bomber jet may have been the "best" medium bomber of the war on either side. It did enter service in 1945 and carried out a few missions, such as trying to destroy the famous "Bridge at Remagen" (which ultimately was destroyed, but only after it no longer mattered). However, the Ar 234 came along too late to make a difference.

|

| A Junkers Ju 88 downed in Moscow. How the pilot brought it down intact among all those buildings was a miracle. |

Some people would choose the Ju 88 as the Luftwaffe’s best overall aircraft. This apparently is because it was used in a wide variety of roles and also helped to fill the critical gap in the Luftwaffe’s lineup as a mediocre bomber. I can understand this view, and it has some merit to it. You certainly may take a different view than me on the relative value of the Ju 88, these are all judgments and evaluations subject to what you view as important in a plane.

|

| Junkers Ju 88. |

The Junkers Ju 88 and its variants certainly did quite a lot of things well. However, in my view, the Ju 88 was certainly a handy plane, but it really fit the old saying of being a jack of all trades but master of none. It was like the sixth man on a basketball team or the utility player on a baseball team. Certainly, the Ju 88 filled an important role. However, most people would view the starting lineup as having the best players.

|

| The Me 323 "Gigant" was one of the most massive cargo planes of World War II. However, it was slow and a favorite target of Allied fighters. |

Conclusion

If I had to pick one indispensable aircraft in the Luftwaffe that was its true workhorse, I would not pick the one that everyone else would choose, namely the Bf 109 fighter. There were other German fighter designs early in the war reasonably similar to the Bf 109’s capabilities. However, Willy Messerschmitt was a savvy businessman and got his bird chosen by using his connections. So, sure, the Bf-109 won the most air battles for the Reich - while it was still winning air battles. There were, after all, 33,984 Bf 109s built.

But the Bf 109 was not the most important workhorse of the Luftwaffe. No, I would choose the Ju 52, the “flying toolshed,” because the Luftwaffe never had another aircraft that could do what it could do nearly as well.

2020