Operation Husky

One of the truly overlooked campaigns of World War II was the

invasion and conquest of Sicily. Invariably, it gets footnoted in between the defeat of Axis forces in North Africa and the invasion of Italy proper, as in, "After invading Sicily, which quickly fell, the Allies moved on to Italy." In fact, there was nothing quick or easy about the invasion of Sicily, and, truth be told, the 40-day Sicilian campaign was more important for the outcome of the war than the subsequent 17 months spent pounding against German defenses on the Italian peninsula.

|

| Sicily was dirty, poverty-stricken and dangerous. Here, a US medic of the 3rd Infantry Division tends to an injured soldier while four generations of a barefoot Sicilian family watches. |

Sicily and the conquest of Italy first came onto the Allied radar screen at the Casablanca conference held in January 1943. This conference, held in newly conquered North Africa, basically set Western Allied strategy for the remainder of the war, though nobody realized it at the time. The choice was between an invasion of Italy or a frontal assault on northwestern France. The British, led by General Sir Alan Brooke, were adamantly opposed to any deviation from their "peripheral strategy" in the Mediterranean. Against weak American opposition led by General George C. Marshall, the British on 19 January 1943 fixed Sicily as the next major target. France was left for another day - at first, it was thought that an invasion of France might come up later in 1943, but that was completely unrealistic.

|

| General Montgomery travels in a DUKW, 12 July 1943, during the invasion of Sicily. |

The date of the invasion was fixed for 10 July 1943. This date was not chosen randomly but was based on the very precise timing of the setting of the moon that day. Once again, the Americans wanted something different - Marshall would have preferred 10 June 1943 - and once again the Americans gave in. The British were in no mood to take shortcuts and risk setbacks against an enemy they felt they knew more about than the Americans at that point.

|

| Pantelleria has a forbidding coastline. |

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was placed in overall command of the operation. The first order of business, especially given a large amount of time available after the final conquest of North Africa on 15 May 1943, was pacification the Pelagian group, composed of the islands of Pantelleria, Lampedusa, Lampione and Linos. The Germans had Freyda radar on Pantelleria and Lampedusa, and, in keeping with the risk-averse feeling of the time, it was felt prudent to invade them rather than bypassing (as would have been done in the Pacific Theater of Operations. Pantelleria was known as a "fortified island," which gave it a lot more credit than it deserved. After a month of allied bombing raids on the island, during which some 4,844 tons of bombs were dropped, a final bombing raid on 10-11 June 1943, finished the job. The island's commander, Vice Admiral Gino Pavasi, to signal a surrender after many previous messages to Mussolini about continuing to resist.

|

| The surrender of Pantelleria was big news at the time. |

Pantelleria revealed a problem for the Axis that was going to be decisive: aside from some highly political Fascist "Blackshirt" formations, ordinary Italian soldiers had no desire to fight. Thus, the large Italian troop concentrations which looked so impressive on Hitler's 1:1000 maps were deceptive and largely (but not entirely) ineffective. No solution to this ever was found, and Italian disaffection was a major cause of the ultimate Axis collapse. The other nearby islands received similar treatment, and all had surrendered and been occupied within a few days. The Allies now had a springboard to Sicily that, at its closest point, was only 53 air miles away.

Operation Mincemeat

|

| Glyndwr Michael aka Major Martin in his final service to King and country. |

The Allies also had a problem. Sicily was believed to be well-defended for political reasons. This would be the first major invasion of pre-war Axis territory (leaving aside Italian interests in Africa, including Ethiopia), and Mussolini would look like a fool if his promises of conquest wound up losing the Italians what they already had. Sicily also was a pretty obvious next objective (others were Sardinia and the Balkans), and in wartime, you never want to be too obvious about your intentions no matter how strong your forces. The British had a general plan of disinformation, Operation Barclay, intended to confuse Axis intelligence about British plans in the Mediterranean. To this, they added the notorious Operation Mincemeat. This ghoulish operation, originating with Flight Lieutenant Charles Cholmondeley and Lieutenant Commander Ewen Montagu, involved releasing information to the Axis in the most innocuous way possible to make it appear legitimate and genuine.

|

| Ewen Montagu. |

It would suggest that the Allies were not interested in Sicily, but rather the Balkans. The beauty of this plan was that it corresponded with a significant line of thinking in Axis circles (particularly Hitler), and that always makes for the best sort of deception campaign. "Secret documents" were prepared and placed in a briefcase attached by handcuffs to the corpse of a homeless man, one Glyndwr Michael. Michael had died from ingesting rat poison containing phosphorus (the identity has been disputed). The corpse had papers identifying it as Major William Martin, Royal Marines. "Major Martin" was then released just off the Spanish mainland near Huelva in Andalusia) by submarine (the Seraph, used in other spy missions as well). The intended implication was that Major Martin had been a casualty of a plane crash or shipwreck and obtaining the secret Allied plans was a windfall for the Axis. The Allies cynically assumed that the "neutral" Spanish would draw the obvious inferences and could not send this "vital" information to the Germans fast enough. They were right.

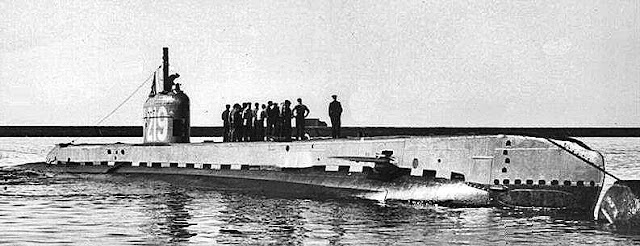

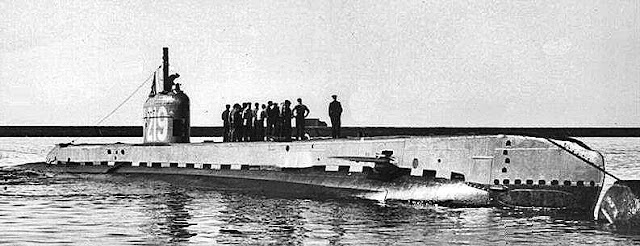

|

| HMS Seraph, used in "Mincemeat." |

The Germans did take the information as genuine; they had lost highly classified invasion information themselves in similar ways on both fronts early in the war (both from plane crashes). However, Operation Mincemeat was a detail to Operation Husky, the period at the end of a sentence. While beloved of "cloak and dagger" types for its cleverness and success, Operation Mincemeat's impact on the war is highly debatable. Those who believe that it was an important deception point to the Wehrmacht sending Field Marshal Erwin Rommel to the Balkans to take command just prior to the invasion of Sicily. They also point to certain related troop movements from the Russian front, including three Panzer Divisions.

|

| The officers of HM Submarine SERAPH upon her return to Portsmouth after operations in the Mediterranean, 24 December 1943. Lieutenant N L A Jewell, MBE, RN, center, had been the commanding officer during Operation Mincemeat. He said prayers before the body was delivered into the sea. They appear to have the appropriate devil-may-care attitudes suitable for the old false-mustache stuff. |

While all that sounds very significant, Rommel was never intended to take over military operation in Sicily (he was widely considered to have become a pessimist worn out by his North Africa campaign) and was quickly re-routed to Northern Italy to take command. That was a quiet sector more important for diplomatic than military reasons, and there Rommel accomplished everything in a timely fashion. On the other front, the panzer divisions would not have altered the outcome at Kursk anyway, handy as they would have been (the German had severely underestimated Soviet strength on that sector), and of course, the panzer divisions were fully employed to good use later. The transfer induced the Wehrmacht to create a powerful reserve, which Hitler otherwise would not allow but which most would agree that the Heer badly needed.

|

| Still from "The Man Who Never Was." |

Operation Mincemeat was not disclosed to the public until the 1950s. The 1956 Ronald Neame film "The Man Who Never Was" starring Clifton Webb and Gloria Grahame gave it wide publicity, and it remains probably the most famous spy operation of the war.

German Dispositions

|

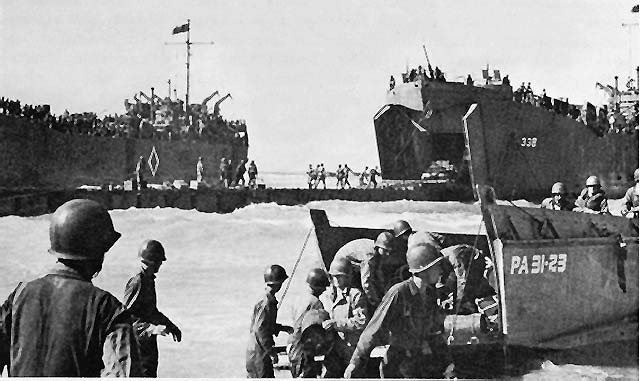

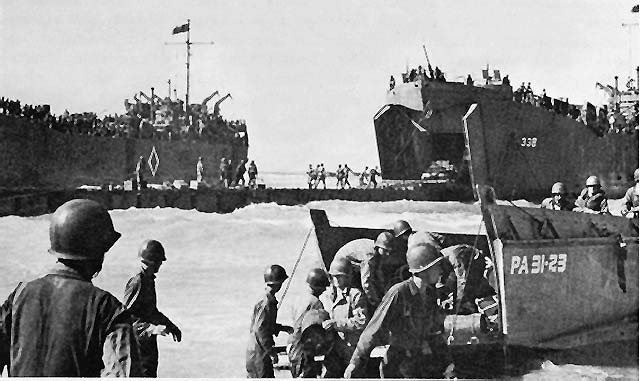

| The nature of the beaches at Gela required LSTs to use pontoon causeways in order to get equipment ashore. These were vulnerable to a Luftwaffe attack, so they had to move quickly. |

The Germans in southern Italy were led by Field Marshall Albert Kesselring. Strategic planning, though, was hindered by the fact that Italy was an ally, not an occupied country where the Germans could do as they pleased. This also would prove an integral part of events throughout the Sicilian campaign. Mussolini had been resistant to German forces on Italian soil throughout the war, but the quick fall of the Pelagian chain made him change his mind. While Italian General Ambrosio remained in overall command of Sicily, and Commando Supremo had overall authority, additional German troops received authorization to move across to Messina to join the light Luftwaffe and garrison troops that had been there previously. The island's nominal commander was Alfredo Guzzoni of the Italian 6th Army.

|

| Plan Husky 8 called for British forces to take the short road to Messina, while the Americans occupied the majority of the island. |

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, who had been recalled from North Africa before the final defeat there and briefly sent to Greece due in part to Operation Mincemeat, was placed in charge of Northern Italy. Rommel was well-known and liked in Italy, and he had established his fame there during World War I at the battle of Caporetto. He shepherded in numerous German forces which ultimately neutralized Italy as a back-door entrance to the Reich. A shooting war easily could have broken out between the Italians and the Germans at the border, but ultimately the Italians gave the Wehrmacht open access.

|

| Street scene in Gela during the invasion. |

In Sicily itself, the Italian 6th Army was basically a static, garrison type of army. It received only a quarter of the supplies that it needed and had small detachments each covering many miles of the coast. There were a few relatively good formations, such as the Livorno (4th) Assault and Landing Division, but in general, the defenses were held by men who didn't want to be there and had little with which to fight. The 6th Army's large ration strength undoubtedly fostered misleading assumptions back at Commando Supremo.

|

| A US Army map showing Axis dispositions prior to the Allied invasion. The Naval Defense Areas along the East Coast are clearly marked and greatly impeded the British advance. |

That said, there also were some quite good troops on Sicily. The best defenses were in Naval Fortress Areas. These zones, like medieval castles, had ample supplies and equipment, along with fixed defenses and, most importantly, strong morale. These fortified areas were at Trapani, Messina-Reggio, and Syracuse-Augusta. These positions could act as "hedgehogs" to provide defense strongpoints even as the rest of the island was virtually defenseless. These areas greatly slowed the British advance up the east coast.

|

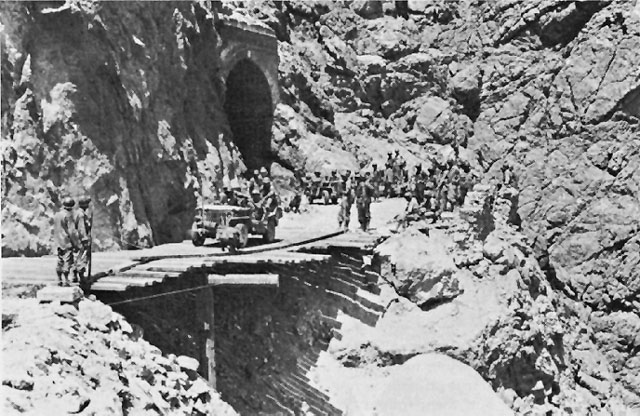

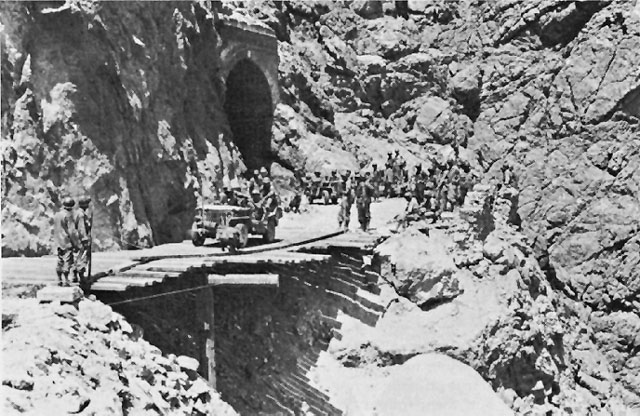

| The 10th Engineer Battalion moved up to restore a highway bridge for vehicular traffic after it was blown by the retreating 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. By hanging "a bridge in the sky" the engineers were able to permit a jeep carrying General Truscott to cross it within 18 hours. |

German troops on Sicily were the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, under Major General Eberhard Rodt, and The Hermann Goering Panzer Division under Lieutenant General Paul Conrath. General Rodt was infamous for his failure to prevent mice from eating the electrical insulation from his tanks outside of Stalingrad, which incapacitated them and contributed to the encirclement there. He was, however, a very capable defensive tactician. Conrath was a Goering crony who had little combat experience, but his troops were elite. In addition, there were scattered survivors from the North African campaign, some of whom had been destined to go there before the final collapse.

|

| A US Army Sherman tank moves past Sicily's rugged terrain in mid-July 1943. |

The Americans and the British had difficulty coming up with an invasion plan. It went through numerous drafts. Finally, under Plan Husky 8, it was decided that the British would land in the extreme south and head straight toward Messina, while the Americans would land in the southwest and occupy the rest of the island. Ultimately, the two forces each would be wholly self-supporting and divided by Mount Etna. The plan left who would get to Messina first - the closest city to the Italian mainland, and occupation of which was sure to conclude the campaign - an open question. This resulted in "the race to Messina." The British had the shortest and most direct route, but the Americans potentially faced lighter opposition.

D-Day for Sicily, 10 July 1943

The invasion forces set out late on 9 July 1943. There was a combination of airborne troops and sea-borne landings. Taking off from near Kairouan, Tunisia, 147 tow planes and gliders carried 2,075 men and their equipment, including jeeps and artillery. Their objectives were various key points inland, such as bridges. They were to hold until relieved. Due to effective antiaircraft fire and sheer confusion in the dark night (as had, of course, been planned), only 12 of the gliders hit their landing zones. The rest (65) crashed into the sea, were shot down, or landed (59) at random spots far from their objectives.

The British sea-borne troops fared better. British 8th Army had no difficulty landing south of Syracuse, led by the 30th Corps at Avola and the 51st Highland Division and 1st Canadian Infantry Division further south at Pachino. The 5th Infantry Division further north found Syracuse almost abandoned, but finally ran into some Germans at Priolo midway between Syracuse and the real prize, Augusta. As was often the case with the Wehrmacht, this effective defense was mounted by scratch troops designated Brigade Schmalz which hurried down from Catania. Without them, the battle for the island might have taken only days rather than weeks.

The American 7th Army landing at Gela, under command of

Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr., also had trouble with its airborne troops, but the seaborne invasion went smoothly. The dispersal of the US airborne forces of the 505th Regimental Combat Team saw many men landed at random spots, but it had the fringe benefit of causing mass confusion behind Axis lines - something that would be repeated on D-Day in Normandy. The seaborne Western Task Force, with a full array of landing craft that would later be used in Normandy, landed the 45th Infantry Division, the 1st Infantry Division (the "Big Red One") under Terry Allen, and 3rd Infantry Division under Major General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. By nightfall on the 10th, all Allied objectives had been taken against very light resistance.

Axis Counter-Attacks

The Italians on Sicily obviously weren't fighting. There were reports of Italian soldiers quickly defecting, helping the Allies unload their equipment, and asking to be taken to Brooklyn. The Germans, however, had better resources. The Luftwaffe staged very effective interdictions against the LSTs (tank landing craft), causing the Americans, in particular, to be low on armor early in the campaign. Conrath in command of the Hermann Goering attacked the American right flank, hoping to prevent a link-up with the British. On the Americans' north flank, Italian Mobile Group E at Niscemi hoped to catch the Americans in a giant pincer attack. These Axis forces were not particularly strong, but they did have good equipment and good morale.

|

| The Luftwaffe blows up a US munitions ship off of Gela during the invasion. |

The Italians attacked first, on time early in the morning of the invasion and in a disciplined fashion. Using cast-off French tanks and even some from World War I, the Italians made it all the way into Gela, an astonishing feat. They were only stopped by naval gunfire and combat engineers firing bazookas from rooftops. It was a tremendous illustration of what the Italian Army could have been capable of given proper equipment, training, and leadership.

|

| General Conrath with his division's namesake, Hermann Goering. |

Conrath, on the other side of the American invasion beaches, took his sweet time attacking invasion morning. As was the case with SS units (the Goering was the top Luftwaffe unit, but had all the trappings of an SS formation), his elite division was determined to get everything just-so before entering the fray. Divided up into two columns, the Hermann Goering Division did not attack until hours after the Italians, well into the afternoon. This lost the advantages of a coordinated attack that may have carried the day. As it was, the Luftwaffe troops made some progress, but once again, naval gunfire proved decisive. General Guzzoni, a good tactician even if his own troops were largely useless, tried to get Conrath to attack again that day, but by 4 p.m. Conrath had had enough and, in a somewhat high-handed manner, refused. Meanwhile, confusion in the Axis command left the nearby 15th Panzer Grenadier Division virtually inactive that entire day.

|

| The USS Savannah (CL-42) was instrumental in the invasion of Sicily. Here, it is hit by a German radio-controlled bomb while supporting Allied forces ashore during the Salerno operation, 11 September 1943. |

The Italians and the Goering Division tried again on the morning of the 11th. The Italians had just about the same amount of success as the previous day, getting barely into Gela but no further. Conrath's men, however, fared much better. The Goering Division actually made it to the invasion beaches and threatened the entire invasion. If there was one German counter-attack that could have changed the course of the entire war, this was it. July 11, 1943, a day that is long forgotten by the public, was the day that the Axis could have turned things around and solidified their hold on Europe for perhaps years longer.

|

| General Patton on the beach at Gela, 11 July 1943. |

The Axis forces thought they had defeated the invasion, and messages were sent over the radio (one or two apparently by the Americans themselves) saying that the invasion forces were re-embarking. The naval artillery from the American cruisers parked offshore, though, took their toll. The USS Savannah and Boise used their 6-inch guns to blast the German Tigers and Panzer IIIs and IVs as they approached the shore. Dozens of panzers were knocked out in a vicious barrage. Perhaps if the Goering unit had coordinated the attack better with the Italians, or if there had been one more panzer division available, or if the Luftwaffe had superiority, things would have turned out differently and the American half of the invasion repelled. Ultimately, though, after extremely heavy losses, Conrath again had to withdraw. His forces remained in the vicinity for a while, but never again threatened the invasion. It had been a very close call for the Americans.

Hard Battles

After that, the campaign basically was decided, but there was a lot of hard fighting left to do. Hitler accepted that the invasion could not be defeated at the beaches, but he only sparingly sent in additional forces because he knew the real battle would be on the mainland (this also undercuts the ultimate value of Mincemeat). He grudgingly sent in the 3rd Regiment of the 1st Parachute (Fallschirmjäger) Division on 12 July (the same day that he called off the Kursk operation) to create a continuous defensive line. The Americans under General Patton raced to occupy western Sicily, against steady resistance Rodt's troops, while the British hammered away at the growing German defenses south of Messina. A bitter battle developed for the key town of Troina, which took almost a week to overcome. A new German commander arrived who, while technically subordinate to General Guzzoni, in fact, controlled all Axis operation.

|

| General Hans Hube was one of the last men out of Stalingrad, taken out at gunpoint by the SS when he refused to leave his men. He later saved the 1st Panzer Army after it was encircled in Russia by making a desperate retrograde movement. |

General Hans Valentin Hube was one of the most capable commanders in the Wehrmacht, and the German forces on the island now became the XIVth Panzer Corps. Hube quickly realized that the island could not be defended indefinitely, which was Mussolini's only hope. He implemented a plan of phased withdrawals by his remaining forces, centered around Mount Etna so that he would get his troops to Messina intact before any of the Allies. This would allow their retreat to the Italian mainland for the inevitable battle there.

|

| British General Montgomery and US General Patton, commanders of their respective armies, did not like each other and engaged in a bitter race to capture Messina first. |

Hube's plan worked perfectly, but two German divisions were not enough. Hitler helpfully, after much indecision due to competing demands in the Mediterranean and Ukraine, authorized a third German division, the 29th Panzer Grenadier, to enter Sicily on 21 July. That gave Hube enough forces to build a continuous line against the Allies in an arc around Messina. General Patton, meanwhile, swiftly occupied all of western Sicily, perhaps unnecessarily because the Germans weren't really defending it anyway. His forces closed near the Germans north of Mount Etna, while the British ground forward slowly against the dug-in Germans to the southeast of the volcano. The narrow coast roads on both sides of the volcano had numerous bridges which the Germans blew up as they retreated, slowing the Allies greatly. It became a matter of honor as to which Allied army would take Messina and end the campaign, the Americans or the British. The strain began wearing on the Allied commanders, leading to the infamous Patton "slapping incident" on 3 August 1943.

|

| A badly defaced portrait of Mussolini, pierced by a bayonet and with several pistol shots to the head, hangs from a tree along the road from Messina to the Sicilian ferry crossing to the Italian mainland following the liberation of Sicily on 17 August 1943. |

General Hube, meanwhile, was a veteran of Stalingrad and knew not to overplay his own hand. He retreated in methodical fashion, losing as few troops as possible while delaying the Allies but not trying to defeat them. The collapse of Italian resistance on Sicily, though, was too much for Mussolini to withstand; he was removed from office in a coup on 25 July 1943 due to the Italian Army's ineffectiveness. The new Badoglio government professed loyalty to the Axis cause, but pretty much everyone surmised that the Italians would either surrender or change sides soon. This gave new urgency to Hube's plan to escape with his troops through Messina.

Operation Lehrgang

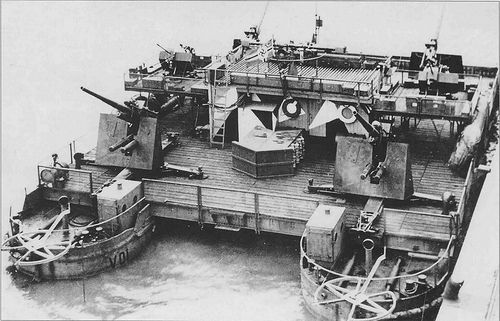

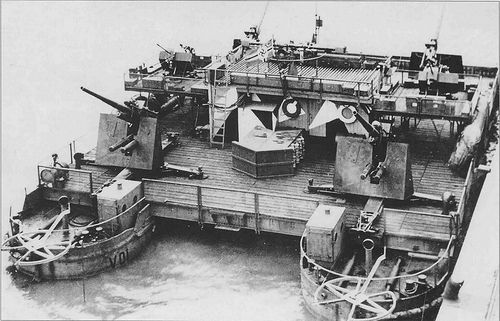

Operation Lehrgang was the German withdrawal across the Straits of Messina. It was accomplished using Siebel ferries, which were double-ended pontoon-supported motorized rafts, along with some other naval barges and a couple of Italian ferries.

|

| A German Siebel ferry, here at anchor carrying four 88 mm Flak 36 anti-aircraft and two 20 mm FlaK 38 anti-aircraft guns. Used in coastal waters, the Siebel ferry could carry heavy loads. It evacuated just about everything from Sicily. |

The XIVth Panzer Corps escaped to the mainland in methodical fashion from August 11-17. The operation, commanded by Baron von Liebenstein who had performed similar work in the Black Sea, was a huge success. Not only did the Germans evacuate their 39,569 troops, they also took 9,605 vehicles, 94 artillery pieces, and 47 tanks, along with ammunition and other supplies. Basically, they retained everything except some railroad cars. The Italians, using their own ferries, evacuated 62,182 men, 41 artillery pieces, and 227 vehicles. It was an unusual feat for either side, wherein the evacuating troops got out not only with their lives but also with their equipment and fighting strength intact.

|

| General Patton won the race for Messina. |

General Patton's troops were the first enter Messina, around 7 a.m. on 17 August 1943. It was about an hour after General Hube had left. General Patton rode into town about 10 a.m. - with enemy shells still falling nearby from the mainland - to end the campaign once and for all. Sicily was now in Allied hands, but the much harder battle for the Italian mainland still lay ahead.

In summary, the Sicily campaign was of huge importance to the course of the war even though it is given short shrift in the history books. Sicily itself was not strategically vital, but it set up some of the most far-reaching consequences of the war. Primarily and most significantly, the invasion caused the downfall of Mussolini. This was no small matter, as his downfall eventually led Italy to change sides to join the Allies, which was much more important than many people think due to economic as well as political ramifications. More subtly, but also of tremendous importance, the invasion of Sicily served as almost a dress rehearsal for the ultimately more decisive invasion of Normandy 11 months later. Aside from simply getting used to the equipment (much of which was re-used on D-Day), Allied soldiers learned to keep the British and American sectors of an invasion front connected rather than separated, had a chance to practice re-supply techniques, saw the trouble that the Luftwaffe could cause if not properly contained, suffered the consequences of not getting armored support on the beaches quickly, and learned valuable lessons about how to coordinate airborne assaults with contested beach landings. Sicily also provided an ideal launching pad for operations against the Italian mainland that began only a few weeks later.

2020