Hitler's Most Successful Message During His Rise

|

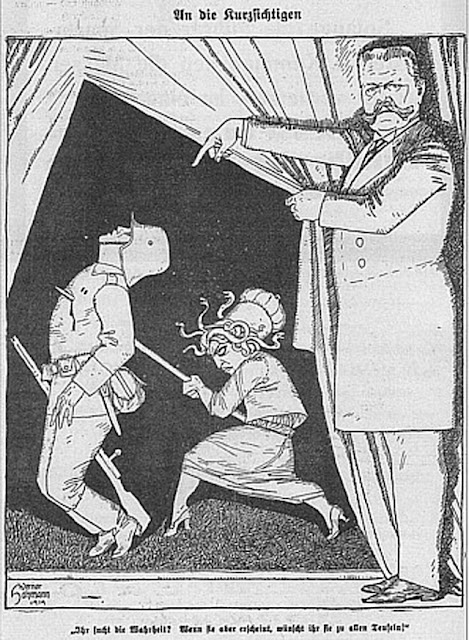

| A contemporary illustration of the "stab in the back" theory. |

What was this "stab in the back" theory that is so often associated with Adolf Hitler and the Second World War? It was a simplistic, erroneous, and distorted explanation for Germany's defeat during World War I. It is said that the seeds for World War II were planted during the conclusion of World War I. The "stab in the back" theory played a major role in Hitler's rise to power and the German desire to avenge past defeats.

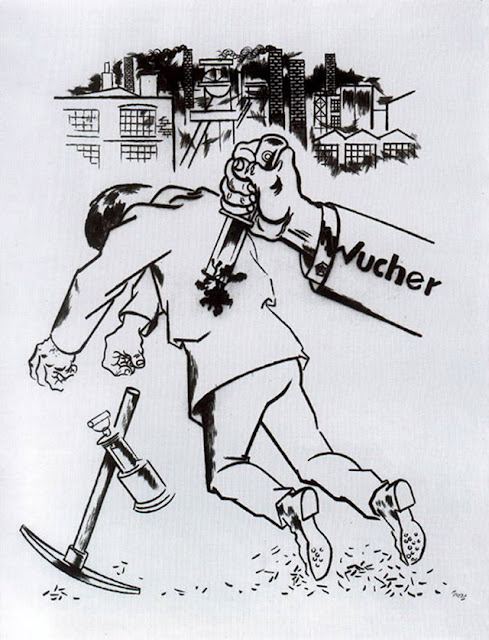

The basic "stab in the back" theory stated that the German military was not responsible for the loss of World War I because uprisings and betrayals at the homefront caused the German government to surrender while the war was still winnable, or at least before the Army was defeated. These uprisings and betrayals supposedly included actions by sinister actors, including communists and Jews. These actions "stabbed the German Army in the back" at a pivotal moment and deprived it of victory.

It is critical to point out here that there is and never was direct evidence to prove the "stab in the back" theory. It is an early example of a conspiracy theory that is believed because it is more comfortable to do so than to accept the pitiless reality. Everything surrounding the "stab in the back" theory is circumstantial, highly debatable, belied by actual evidence, and based on stereotypes of standard "enemies" and "outsiders" in dominant German culture.

The Dolchstoß theory, or Dolchstoßlegende as the Germans call the "stab in the back" theory, became a central feature of Third Reich propaganda with increasing anti-Semitic overtones. It was promulgated by German generals who failed during World War I and were looking for easy excuses for their own failures. It also was a way to stiffen resentment of communism, blamed along with the Jews for the uprising.

Going over the immediate background is necessary to understand the "stab in the back" theory and why it was contrary to the facts.

The 1918 Situation

By late 1918, World War I (then usually called the "Great War") had ground on for four long years. German fortunes had their ups and downs during that time, but by September 1918 it was in serious trouble.

German defeat was extremely likely by the fall of 1918. The Western Allies were advancing at what seemed like an impossible speed after years of trench warfare where the front hadn't change more than a hundred meters every year. The Australian, Canadian, British and French armies launched the successful Hundred Days Offensive in August 1918 with the Battle of Amiens and Battle of Montdidier. The initial offensive enjoyed immediate success and gained 12 miles (19 km).

|

| German prisoners carry Canadian wounded past a Canadian tank during the Battle of Amiens, August 1918 (Canadian War Museum). |

The German collapse was so swift and unexpected that General der Infanterie Erich Ludendorff, effectively running the German war effort as First Quartermaster General of the Great General Staff, referred to 8 August as “Der Schwarztag des Deutschen Heeres” (the Black Day of the German Army). The Allied success led to further offensives in August, such as the Third Army at Albert (the Battle of Albert) and the Second Battle of Noyon.

Things just went from bad to worse for the Germans. The arrival of the Americans was especially dispiriting. They were fresh troops, well-armed, and physically impressive (on average, the Americans were taller than other soldiers on either side). Crown Prince Ruprecht, during a 15 August 1918 conversation with Prince Max of Baden, lamented:

The Americans are multiplying in a way we never dreamt of... At the present time, there already are thirty-one American divisions in France.

In a war that everyone by now knew was fairly evenly balanced before the arrival of the U.S. Army, this sudden influx of powerful forces had extremely negative connotations.

|

| Canadian troops using tanks along the Arras-Cambrai Road before the Battle of Cambrai, September 1918 (Library and Archives Canada 3194821). |

But at this point, it wasn't even clear if the Allies even needed American troops. The British broke the main German line of defense called the "Hindenburg Line" at the Second Battle of Cambra in early October and the Germans retreated rapidly, abandoning large supply stores and equipment along the way. These sudden Allied victories were rapidly eating up all of the German war gains in the West.

However, as dramatic as the Allies' 1918 breakthrough was, Germany was not yet militarily defeated even though that result seemed inevitable to many observers. The German Army was still fighting outside Germany’s border. Germany had defeated the Russian Empire and forced an advantageous peace, occupying vast stretches of territory in the East. This realized a long-held dream of many Germans for eastward expansion, taking land from people many considered backward and inferior.

Just six months before the surrender, a German offensive in the West had some success and almost broke the French Army. This was known as "Operation Michael" and had brought the German Army to the Marne River for the first time since 1918. There, they were finally repulsed with the assistance of American troops under General John "Black Jack" Pershing entering combat for the first time.

|

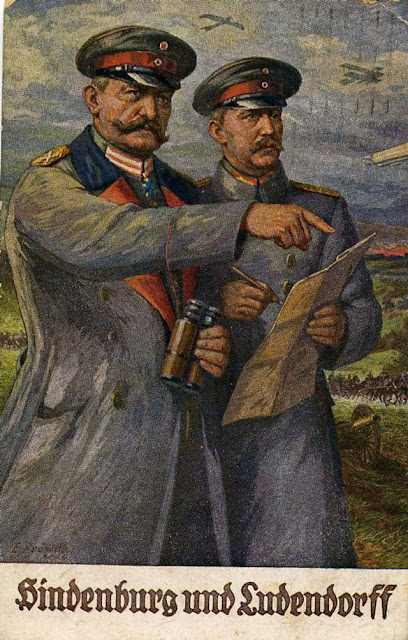

| General Paul von Hindenburg, Kaiser Wilhelm, and General Erich Ludendorff. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (cph 3a42618) |

Ludendorff's Personal Issues

So, the German war situation in 1918 was dire. Germany, blockaded by the Allies, no longer had the resources to continue the war. The "stab in the back" theory, though, had nothing to do with that. Its origins were far more ethereal.

|

| Russian soldiers surrender at the Battle of Tannenberg, one of the great German victories of World War I. |

Ludendorff, nominally under the command of Chief of the German Great General Staff Paul von Hindenburg, was the general actually running the German military. His strategies in 1914 prevented a potentially war-ending Russian breakthrough at the Battle of Tannenburg. Hindenburg involved himself with strategy now and then, but mostly he just acted as the "front man" for the Duo. He would entertain the Kaiser and diplomats over cognac and schnapps during the evening and receive briefings on the state of the war from Ludendorff.

The Allies' Hundred Days Offensive claimed its most prominent victim in the German High Command. Ludendorff had a classic nervous breakdown from all the stress. Among other things, his son had fallen in combat and this affected Ludendorff, who took to visiting his son's grave at Avesnes, greatly. Ludendorff's boss, Hindenburg, grew concerned about Ludendorff's condition and asked his own doctor to take a look. Hindenburg's physician observed Ludendorff getting increasingly agitated, with mood swings and more drinking, and referred Ludendorff to a psychiatrist, Dr. Hochheimer. The psychiatrist quickly divined that the problem was Ludendorff's micro-managing of the troops.

|

| Paul von Hindenburg (left) and Erich Ludendorff (right) took over control of the German war effort as a team, replace Erich von Falkenhayn in August 1916. Informally, they were known as "The Duo." |

Psychiatry was a new profession in 1918, but Hochheimer had some interesting ideas. He recommended that Ludendorff take deeper breaths, relax, maybe try some yodeling to let off steam, take some days off, and basically ordered him to take a vacation. However, Ludendorff could not break away and his condition grew worse throughout the fall of 1918.

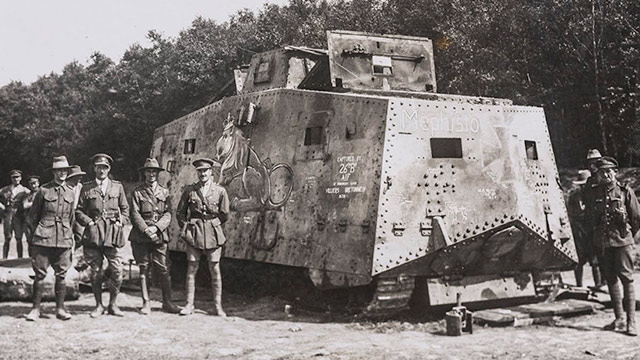

Ludendorff's mental state is significant because his views on the military situation were colored by his personal problems. He had very good advice on the true state of affairs and even wrote an insightful paper that cast much of the blame for the Allies' sudden success on their use of mass tanks (the British used 500 tanks at the breakthrough Battle of Cambrai).

The Germans struggled to develop effective defenses against tanks and produced very few tanks of their own. The ones that Germany did build were ponderous and ineffective. While Germany did capture some useable Allied tanks and put them into service, there weren't nearly enough to hold back the Allies.

So, there were good reasons for the Allies' sudden success. Ludendorff knew all about them. In fact, he knew the reasons so well that he was educating his subordinate commanders about them. But, for convenience and due to his personal issues, Ludendorff suddenly developed a radical new theory to explain his own failures as a commander.

|

| A captured World War I German tank. They were large, ponderous, underpowered, and ineffective. |

The Origination of the Stab in the Back Theory

To summarize this section: Ludendorff actually knew the war was lost and took decisive actions to make sure it ended. But, once he had done that, he quickly turned around and concocted a theory to absolve himself and the military of any blame for the defeat.

Ludendorff's mercurial temperament in the fall of 1918 created a lot of anxiety at the highest levels of the German government. He told Hindenburg on 28 September 1918 that the government needed to sue for peace immediately. Rattled by this demand, Hindenburg took Ludendorff to see the Kaiser the following day. Ludendorff said the same thing, only promising to be able to retreat to the German border to avoid a "shameful peace." This started the ball rolling for peace talks and the fall of the German government.

Once he had vented to the Kaiser about the true situation at the front and established a framework for peace negotiations, though, Ludendorff changed his tune. He took an entirely different view at a cabinet meeting on 9 October when he claimed the army could protect Germany's borders into 1919. Ludendorff opined that Germany still had time to negotiate from a position of strength even though, due to his own agitation, this was now impossible. He reiterated this at a 14 October cabinet meeting. By then, a new German government full of Socialists was considering President Wilson's peace proposals seriously.

|

| Russian soldiers charge at the Battle of Tannenberg. |

A close look at Ludendorff's own history suggests that his mental issues during the final months of the war were not unusual for him. His sole claim to fame was the Battle of Tannenberg in August 1914, an undeniably great victory. However, Hindenburg revealed shortly before his death that Ludendorff had completely lost his nerve and become severely agitated at a critical point in the battle, right before a great encirclement won it. This is exactly the kind of behavior Ludendorff demonstrated in September 2018, completely losing his nerve under stress. This revelation put everything that happened at the end of World War I into proper perspective.

Another inconvenient fact about the Tannenberg victory was that Ludendorff's responsibility is a bit questionable. Two subordinate commanders, General Max Hoffmann and Lt. Gen. Hermann von François, played much larger roles in issuing the commands that led to victory. At key points in the battle, François, a field commander, acted on his own initiative without orders and achieved vital results. Without the dash and initiative of François, victory may have slipped away.

Hoffmann was Chief of Staff of the Eastern Front during the Battle of Tannenberg and its follow-up, the Battle of the Masurian Lakes. Anyone familiar with military commands knows that the chief of staff is usually the guy running around getting things done. After receiving no credit, Hoffmann remained bitter for the rest of his life.

However, it was in the interest of the German Empire to create heroes for morale purposes. Ludendorff and Hindenburg were technically in command and thus received all of the plaudits. Let's just say that Ludendorff may not have been quite the master battle strategist that he was made out to be by the propaganda bureaus. However, the public adored the Duo.

I'm sure you've heard of Ludendorff and Hindenburg. Everyone has. Have you ever heard of Hoffmann and François? Unless you are a student of war history, probably not. That is a vivid demonstration of the power of the press. However, Hoffmann is still used as a model for the ideal staff officer at the United States Army Command and General Staff College. He was the German unsung hero of World War I.

|

| Hindenburg looks through field glasses at the Battle of Tannenberg while Ludendorff (second from right) and Hoffman - the forgotten man - look on. |

Even Hindenburg was a bit resentful of the acclaim that Ludendorff received. Late in life, he pointedly remarked that he did have some impact on the victory, stating, "I was, after all, the instructor of tactics at the War Academy for six years."

It is important to emphasize here that the Battle of Tannenberg indeed was a great German victory that saved the Empire. The point is that the German government found it expedient to have the press tout Ludendorff as a master strategist when, in fact, the victory was attributable to the efforts of others as much as the role he played in it. This led to his elevation to a position where he was running the entire war effort. This fulfilled the cynical Peter principle, which states that people will be promoted to their maximum level of incompetence.

Ludendorff's erratic behavior finally brought about his downfall. On 24 October 1918, he sent an unauthorized telegram to the troops telling them that President Woodrow Wilson's terms for ending the war were "unacceptable" and that the troops must fight on. He did this without going through normal channels or consulting the civilian government.

Kaiser Wilhelm found Ludendorff's telegram insulting to his own power. He quickly called Ludendorff and Hindenburg in and abruptly fired Ludendorff for insubordination. Hindenburg offered to resign as well but was flatly refused.

|

| 1917 German Sturmpanzerwagen A7V tank. |

It is now that the Stab in the Back theory developed. Ludendorff fled to Sweden using a disguise and false papers to wait until revolutionary fervor in Berlin cooled down. Hindenburg retired (again) in June 1919 to Hannover. Both men wrote memoirs that created the "stab in the back' thesis, that the war was going fine until problems developed on the homefront.

However, Ludendorff wrote his memoirs in a mad rush, publishing "My War Memories" on 1 January 1919. In this, he was the first to write about the "stab in the back" by the homefront. Hindenburg's memoirs (written with the aid of a journalist who undoubtedly was familiar with Ludendorff's version) just repeats Ludendorff's stab-in-the-back theory but greatly amplified its exposure to the public.

The facts, though, run counter to Ludendorff's sudden self-serving explanation for Germany's defeat. He was the main advocate of seeking peace in August and September 1918 due to the Allies' sudden success at breaking the logjam on the Western Front. The homefront had nothing to do with Ludendorff's opinion then. It was only after a change in government to one with many Socialists in it (who could be blamed for the defeat) in October 1918 that he changed his tune and claimed the army could fight on, though to what purpose is unclear.

Even before that, Ludendorff had established a tendency to blame others for the growing crisis. On 6 September 1918, he told the assembled army chiefs of staff at a meeting held at his headquarters in Avesnes that the blame for recent defeats lay with failures by the troops and their officers. About Ludendorff's comments at this meeting, General Friedrich von Lossberg wrote in his 1939 memoirs that "the real fault lay in his own defective generalship."

|

| Dr. Karl Liebknecht proclaims a German socialist republic in November 1918. The real uprisings began after the war was over, such as the Spartacist uprising of January 1919. |

It is important to note that while Ludendorff was panicking in August and September 1918, he never blamed the army's troubles on the homefront. That was never even a consideration. The Allies were beating the German Army on the field of battle, and that was decisive to the outcome of the war. The revolts and mutinies came later and were likely in part instigated by the military defeats. The famous Kiel Mutiny did not occur until 3 November 1918, long after the war was decided.

Germany's allies were dropping out during the fall of 2018 without regard to Germany's internal issues. Bulgaria capitulated on 29 September (right when Ludendorff was telling the Kaiser he should do the same), the Ottoman Empire surrendered on 30 October (just as Ludendorff was leaving his position), and on 3 November the Austro-Hungarian Empire gave up (and ceased to exist). If Germany wasn't winning the war with these powerful partners, it's hard to see how they could get along without them. There were no "stabs in the back" in these other countries. The clear implication is that the problem was the overall military balance of power.

The beauty of the "stab in the back" theory from Ludendorff's perspective was that it could not be disproven. It also absolved him from all responsibility for the defeat. Other top German generals, though, completely disagreed with this theory. On 27 May 1922, General Wilhelm Groener, for instance, wrote the following:

It would be the greatest injustice to defame the German people for their collapse at the end of the lost world war. They had sacrificed their youth on the battlefields. They had proven themselves by magnificent feats of arms in the field, in unrelenting work, in privation and sufferings in the homeland. They had been led to the mountain peak of an illusionary world in which they were held by hope after hope of certain victory... In the end, the blame for the continued self-deception and the mistaken employment of defensive tactics rests on the military. The victories... were not victories in the strategic and political sense.

Ludendorff went on to support revolutionary crackpots who embraced his stab-in-the-back theory for political purposes. These included Wolfgang Kapp and Adolf Hitler, both right-wing extremists who staged unsuccessful coup attempts in the early 1920s.

The stab-in-the-back theory was extremely useful to Hitler, who used it to rouse his followers with the "injustices" of the Treaty of Versailles and the need to re-arm to reclaim Germany's place in the world. The millions of unemployed or underemployed former German soldiers who still felt loyalty to Ludendorff and Hindenburg eagerly embraced this myth, which absolved them and the army for all blame for the defeat.

|

| Ludendorff and Adolf Hitler following the failed 1923 Putsch. 26 March 1924. The Third Reich used this picture for propaganda purposes during the 1930s (see Federal Archive Image 102-16742). |

Conclusion

Germans in 1918 who wanted to be delusional about their war prospects could see certain silver linings despite all the military catastrophes during the Allies' Hundred Days Offensive. If distance makes the heart grow fonder, then time makes a losing military situation more salvageable (especially if it's long in the past and you don't have to go through the added deprivations now). It’s difficult now to understand the “fight to the bitter end” mindset, but it obviously affected a lot of Germans.

Was the “stab in the back” thesis accurate? No. But it had just enough of a kernel of truth to sway the masses for Adolf Hitler’s benefit.

2021

No comments:

Post a Comment