As the war entered its middle phase, Allied air attacks became a huge concern for the German high command. It wasn't so much that they were destroying valuable facilities and killing German civilians - which they most certainly were - but that they were relentless, the trend was toward increasing attacks, and there was no way to stop them. Something had to be done, and fast.

What followed was more a case study in corporate rivalry and changing priorities than aircraft design. The result was the Blohm & Voss BV 155 Interceptor, a promising fighter badly needed by the Germans but which never got into action due to mismanagement and constantly changing focus. It is useful to review designs that did not pan out to learn why - and there are a lot of easily-avoided reasons why the BV 155 project did not wind up contributing to the war effort.

The Messerschmitt company had begun work on a new fighter for naval use in 1942 which was designated Me 155. Due to the restrictions of the Versailles Treaty and Germany's traditional status as primarily a land power, the Kriegsmarine had absolutely no experience with aircraft carriers or fighters that could operate from them. The initial idea was just to use standard Bf 109s adapted for carrier use for a quickie solution, which made sense. This was easier said than done, for simply slapping a new undercarriage on the standard design did not suffice, so a completely new design was requested. For efficiency, the Messerschmitt designers worked up a new fighter design with a more powerful engine that basically was just an outgrowth of the superb Bf 109. This plan guided early development, but the entire theory behind the project collapsed as the work on the Kriegsmarine's aircraft carriers such as the Graf Zeppelin was gradually shut down in 1942-43.

By early 1943, the pressing need had switched from naval aircraft to blunting the Allied bomber swarm. The Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) decided to revamp the promising naval fighter design to its new need - high-altitude interception. Once again, this seemed like a quick solution, short-circuiting the long design and machining phase. Messerschmitt had placed the BV 155 on the back burner, but the RLM finally was beginning to realize that time was growing short. Thus, to speed it up, it shifted the project to the aircraft subsidiary of Blohm & Voss - which wasn't nearly as busy because, well, its own designs hadn't been as important to the war effort. So, not only the purpose behind the project changed, but so did the designers.

B&V had originated as a shipyard that had branched out into military aircraft production due to the German rearmament program of the 1930s. Its specialty was flying boat construction, which it did well due to its maritime experience. Perhaps one of the reasons the BV 155 project was given to B&V was because of the original naval connection - which, with the new goal of a land-based high-altitude interceptor, had disappeared completely. However, the project still had those bureaucratic associations. BV was the maritime aviation specialist and had people available to work up the design, even if they weren't really experts at this kind of plane.

The RLM, though, hedged its bets. The plane's further evolution was supposed to be a joint project between the two companies, and B&V needed the help because the project used so many Messerschmitt components. However, the Messerschmitt people resented losing the project and did the usual passive-aggressive things that show displeasure - missing meetings and so forth. By late 1943, the collaboration had collapsed completely, leaving B&V holding the bag. B&V finally decided just to eliminate a lot of Messerschmitt parts, such as the Bf 109 wings and canopy. The RLM accepted the changes, and the new designs certainly provided marginal improvements, but crafting new parts eliminated the efficiency of using off-the-shelf components. This stretched the project out, and time was not something the Germans had in abundance as bombs rained down on their cities and factories.

The BV 155 V1 flew for the first time on 1 September 1944. The outboard radiators from the Messerschmitt design proved too small, and after redesign (including the new canopy and larger rudder) the BV 155 V2 flew on 8 February 1945. The engine went through numerous changes, beginning with the DB 605A-1 liquid-cooled engine of 1,475 PS (1,455 hp, 1,085 kW) and ending with the B&V DB 603U, with power of 1,238 kW (1,660 hp) for takeoff and 1,066 kW (1,430 hp) at 14,935 m (49,000 ft). It would have been competitive at higher altitudes with any fighter of the time aside perhaps from any jets that could reach there, but it was evolutionary, not revolutionary.

Maximum speed:

The project was stumbling toward a conclusion when the war ended. Even if it had entered service, the BV 155 may have been adequate for its limited purposes but never a war-winning design.

There is a rule of effective warfare taught in the military academies: "maintenance of the objective." You must decide what your objective is, and then achieve it without distractions. Adolf Hitler was guilty of violating this rule repeatedly, especially in the Soviet Union during 1941 and 1942, but the rule also applies equally well to non-combat situations. The BV 155 project is a classic example in the corporate sector of what happens when you fail to maintain your objective and start "winging it" on the fly.

Length: 12 m (39 ft 4 in)

Wingspan: 20.5 m (67 ft 3 in)

Height: 3 m (9 ft 10 in)

Wing area: 39 m2 (420 sq ft)

Empty weight: 4,870 kg (10,737 lb)

Gross weight: 5,100 - 5,520 kg (11,244 -12,170 lb) (depending on armament etc.)

Maximum projected takeoff weight: 6,020 kg (13,272 lb)

Fuel capacity: 1,200 l (264 imp gal)

Engine: 1 × Daimler-Benz DB 603A inverted V-12 liquid-cooled piston engine with TKL 15 turbo-charger, 1,200 kW (1,600 hp) for take-off

1,200 kW (1,609 hp) at 10,000 m (32,808 ft)

1,081 kW (1,450 hp) at 15,000 m (49,213 ft)

Propeller: 4-bladed constant speed paddle bladed propeller

2020

What followed was more a case study in corporate rivalry and changing priorities than aircraft design. The result was the Blohm & Voss BV 155 Interceptor, a promising fighter badly needed by the Germans but which never got into action due to mismanagement and constantly changing focus. It is useful to review designs that did not pan out to learn why - and there are a lot of easily-avoided reasons why the BV 155 project did not wind up contributing to the war effort.

|

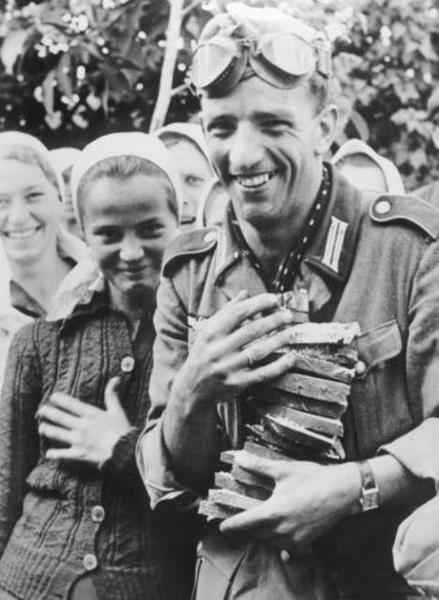

| The BV 155 was characterized by prominent outboard radiators. |

By early 1943, the pressing need had switched from naval aircraft to blunting the Allied bomber swarm. The Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) decided to revamp the promising naval fighter design to its new need - high-altitude interception. Once again, this seemed like a quick solution, short-circuiting the long design and machining phase. Messerschmitt had placed the BV 155 on the back burner, but the RLM finally was beginning to realize that time was growing short. Thus, to speed it up, it shifted the project to the aircraft subsidiary of Blohm & Voss - which wasn't nearly as busy because, well, its own designs hadn't been as important to the war effort. So, not only the purpose behind the project changed, but so did the designers.

B&V had originated as a shipyard that had branched out into military aircraft production due to the German rearmament program of the 1930s. Its specialty was flying boat construction, which it did well due to its maritime experience. Perhaps one of the reasons the BV 155 project was given to B&V was because of the original naval connection - which, with the new goal of a land-based high-altitude interceptor, had disappeared completely. However, the project still had those bureaucratic associations. BV was the maritime aviation specialist and had people available to work up the design, even if they weren't really experts at this kind of plane.

The RLM, though, hedged its bets. The plane's further evolution was supposed to be a joint project between the two companies, and B&V needed the help because the project used so many Messerschmitt components. However, the Messerschmitt people resented losing the project and did the usual passive-aggressive things that show displeasure - missing meetings and so forth. By late 1943, the collaboration had collapsed completely, leaving B&V holding the bag. B&V finally decided just to eliminate a lot of Messerschmitt parts, such as the Bf 109 wings and canopy. The RLM accepted the changes, and the new designs certainly provided marginal improvements, but crafting new parts eliminated the efficiency of using off-the-shelf components. This stretched the project out, and time was not something the Germans had in abundance as bombs rained down on their cities and factories.

The BV 155 V1 flew for the first time on 1 September 1944. The outboard radiators from the Messerschmitt design proved too small, and after redesign (including the new canopy and larger rudder) the BV 155 V2 flew on 8 February 1945. The engine went through numerous changes, beginning with the DB 605A-1 liquid-cooled engine of 1,475 PS (1,455 hp, 1,085 kW) and ending with the B&V DB 603U, with power of 1,238 kW (1,660 hp) for takeoff and 1,066 kW (1,430 hp) at 14,935 m (49,000 ft). It would have been competitive at higher altitudes with any fighter of the time aside perhaps from any jets that could reach there, but it was evolutionary, not revolutionary.

Maximum speed:

- 420 km/h (261 mph; 227 knots) at sea level

- 520 km/h (323 mph) at 6,000 m (19,685 ft)

- 600 km/h (373 mph) at 10,000 m (32,808 ft)

- 650 km/h (404 mph) at 12,000 m (39,370 ft)

- 690 km/h (429 mph) at 16,000 m (52,493 ft)

The project was stumbling toward a conclusion when the war ended. Even if it had entered service, the BV 155 may have been adequate for its limited purposes but never a war-winning design.

There is a rule of effective warfare taught in the military academies: "maintenance of the objective." You must decide what your objective is, and then achieve it without distractions. Adolf Hitler was guilty of violating this rule repeatedly, especially in the Soviet Union during 1941 and 1942, but the rule also applies equally well to non-combat situations. The BV 155 project is a classic example in the corporate sector of what happens when you fail to maintain your objective and start "winging it" on the fly.

BV 155

Crew: 1Length: 12 m (39 ft 4 in)

Wingspan: 20.5 m (67 ft 3 in)

Height: 3 m (9 ft 10 in)

Wing area: 39 m2 (420 sq ft)

Empty weight: 4,870 kg (10,737 lb)

Gross weight: 5,100 - 5,520 kg (11,244 -12,170 lb) (depending on armament etc.)

Maximum projected takeoff weight: 6,020 kg (13,272 lb)

Fuel capacity: 1,200 l (264 imp gal)

Engine: 1 × Daimler-Benz DB 603A inverted V-12 liquid-cooled piston engine with TKL 15 turbo-charger, 1,200 kW (1,600 hp) for take-off

1,200 kW (1,609 hp) at 10,000 m (32,808 ft)

1,081 kW (1,450 hp) at 15,000 m (49,213 ft)

Propeller: 4-bladed constant speed paddle bladed propeller

2020