|

| Bf 110 Zerstörer |

The Messerschmitt Bf 110 (aka "Me 110," and we use both terms interchangeably here) was the Luftwaffe's twin engine heavy fighter. The Bf 110 unfairly acquired a reputation for being a failure, but in fact was a huge asset for the Luftwaffe and a personal favorite of Hermann Goering.

|

| Nice, clean shot of a Bf 110 |

It was a true multi-purpose aircraft that served on all fronts for the duration of the conflict and was constantly improved with enhanced capabilities.

|

| A German twin propelled Messerschmitt BF 110 bomber, nicknamed "Fliegender Haifisch" (Flying Shark), over the English Channel, in August of 1940. (AP Photo) |

Germany was re-arming quickly in the mid-1930s, and Hermann Goering's Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) decided that, in addition to the Bf 109 fighter, it also needed a heavy multipurpose heavily armed aircraft to be called the Kampfzerstörer (battle destroyer), or Zerstörer for short.

In 1935, the RLM published specifications and requested tenders. While seven companies had the ability to respond to the specifications, only Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (Messerschmitt), Focke-Wulf and Henschel submitted proposals.

|

| Me 110 gunner |

Messerschmitt won the competition, making it the supplier of both the light and heavy fighters on which Germany's defense would rest.

|

| A Bf 110 at Sofia-Vrazdebna Teufelskopf, bearing reconnaisance Luftwaffe staffel camouflage |

While the specifications explicitly called for an internal bomb load, Willy Messerschmitt was experienced enough to know that the RLM was always willing to accept non-compliant designs that were of easily demonstrable overall superior design.

|

| Fooling with the Fug III at Athens |

The Bf 110 design provided range, speed and firepower that made it Goering's and RLM procurement boss Ernst Udet's top choice. In fact, it was Udet who saw the promise of the aircraft.

|

| German Messerschmitt BF.110D-1 belonging to Squadron ZG26 "Eagle" in flight over the coast of North Africa. |

He altered the specification requirements so that they more closely resembled the Bf 110's actual capabilities, allowing it to be considered at all.

|

| Stalino, a pilot and his Bf 110 C waiting for a mission |

This was hardly the only time the RLM did this, the Arado 196 seaplane received similar special consideration, and no doubt other aircraft as well.

|

| Flying low, perhaps over a Norwegian fjord |

The first Br 110 prototype flew on 12 May 1936. It was a fast plane, faster, in fact, than the single-engine Bf 109 B-1, and this decided the competition issue between the three choices.

|

| German Messerschmitt Bf 110 from Zerstörergeschwader 26 (3U+DT) with two 900l drop tanks. |

However, with multiple-engine aircraft, competition speeds often bore little resemblance to final, armored and fully equipped versions that are heavier and bulkier.

|

| Bf 110s in desert camo |

The speeds observed in competition thus often are quite fantastic and, in fact, unachievable with production versions. Deliveries of pre-production A-0 versions began in January 1937. The engines were a problem, at first leaving it underpowered and slower than need be, but this was corrected in later versions. Full-scale production began that summer.

|

| View from gunner's seat |

New engines, the Daimler-Benz DB 601 B-1, that were much more suitable for the design became available in late 1938. The DB 601 B-1 was the same engine that was used on the Bf 109E. This became the Bf 110 C series.

|

| The local Bedouin were often quite helpful |

It had a 336 mph (541 km/h) speed and 680 mile (1094 km) range, both of which were excellent pre-war performance marks for any air force. Armament was four 7.92 mm MG 17 machine guns in the upper nose and two 20 mm MG FF/M cannons in the lower part of the nose.

|

| 1944- German Luftwaffe ME-110 fighter planes in action against Allied bombers over Alps. |

Development progressed rapidly. In late 1939, the twin MG FF nose-mount cannon were removed and a larger 277 gallon (1050 Liter) tank was inserted into the ventral fuselage.

|

| That Bf 110 hasn't been repainted yet |

This modification made the aircraft frame bulkier, but gave the plane greatly extended range and lent it the nickname Dackelbauch (dachshund's belly). It also could accept two 238 gallon (900 liter) drop tanks. Various permutations of the tanks and airframe and cannon led to the different D designations.

|

| Me-110 Nightfighter (Nachtjager) with FuG 220 Lichtenstein SN-2 |

The Bf 110 did a good job, but the Luftwaffe tried an overhaul with the Me 210. The Me 210 was designed as a complete replacement for the Bf 110, and was being worked up even before the war began. Unfortunately, the Bf 210 was a failure that quite simply did not fly very well and saw very limited service.

The Bf 110, though an older design, was very reliable and always flew well. It also had room for further improvements, so after a period of inactivity due to the imminence of the 210, upgrades on the 110 were resumed in 1941.

|

| Probably an emergency landing on that field which, as usual, looked so flat and featureless from the air. Oops, didn't see that grass-covered mound. |

This could have been the end of the line for the Bf 110, because the Me 201 became available in mid-1941, but the new plane did not perform well and was withdrawn. This led to the Bf 110 G, which had DB 605B engines giving variable 997 kW at cruising speed and 1085 kW maximum power. The armament was upgraded to two 30 mm machines replacing the lower two 20 mm guns, and the fuselage streamlined. The Bf 110 G-2, G-3 and G-4 collectively became the largest production run and lasted until the end of the war. The 110 G was not the pilots' favorite, but its design changes made it more stable as a night fighter, which had become the Bf 110's most prominent late-war role.

|

| Me-110 Dackelbauch |

Germany was under sustained air assault by the time of the G version, and Bf 110s proved to be capital night fighters. Many were fitted with Schräge Musik (very loosely, "jazz") cannon. These pointed upward at a slant so that the night fighters could cruise under the bomber stream and blast away without having to be at the same altitude as the bombers, which opened them up to more return fire. These were fitted to the back of the cockpit. Another version was the Bf 110 G-2/R1 fitted with a ventral 37 mm Bk 3.7 cannon, similar to the ones on Ju 87 Stukas that were used to attack (in pairs) tanks on the ground. These "Bordkanone" were deadly for Allied bombers.

|

| Me 100 C |

The Bf 110 was ready for the Polish campaign, which was not the case for all the Luftwaffe's promising new aircraft. Many of the Luftwaffe's future leaders cut their teeth in these early combats. The Polish air force was weak, and the Bf 110s could act as escort fighters in attacks on Warsaw. The Bf 110 saw its greatest success during this campaign, which led to all sorts of unrealistic later expectations.

|

| Me-110 C4 |

The Bf 110 also contributed to the defense of Germany early in the war against the French air force, which was not very aggressive or formidable. Late 1939 was a sort of "feeling out" period in which the Bf 110 performed well, and it proved very capable in a daylight bomber defense role. In fact, it was so good that its successes helped to convince the British to abandon daylight attacks.

|

| Me 110 D |

The April 1940 invasion of Denmark and Norway (Operation Weserübung) also heavily committed the Bf 110. Two Zerstörergeschwaders (1 and 76) participated, a total of 64 aircraft. Against the paltry Norwegian air force, this was quite a lot of machines, and they destroyed almost all of the Norwegian aircraft on the ground. They also escorted Ju 52 transports with paratroopers (Fallschirmjäger), defending them against attack by British Gloster Gladiator biplanes. The Bf 110s were dominant against such weak opposition and helped secure vital Oslo-Fornebu airfield despite the fact that ground troops had not yet captured it - the Bf 110 pilots watched the Ju 52s land and face ground attack, then commenced strafing runs to provided intense support that drove off the defenders' ground attacks until men from the Ju 52s and other ground forces could secure the field. It was the ultimate triumph of air power - occupying ground territory with planes - and helped to secure the Luftwaffe's reputation as a devastating instrument of aggression. The long ranges required in Norway led to the Bf 110 D designs with extra fuel tanks - there was no opposition from enemy fighters, so the only limitation on its effectiveness was range. Speed and maneuverability were unimportant in that role, which devolved to patrolling the long, winding, seemingly endless Norwegian coastline.

|

| Me 110 E |

The Bf 110s continued to perform well during the first half of 1940, continuing to serve satisfactorily as fighters during the Battle of France. The Bf 110s were a good match for older British and French bombers of the time and often wiped out in devastating fashion small streams of 10-15 bombers. Everyone began to see the Bf 110 as a more powerful Bf 109 fighter, in addition to all of its other capabilities.

|

| Me-110 F |

Things changed, though, as the British started throwing more of their newer Hurricanes and Spitfires into the mix. They had been keeping those cutting-edge aircraft at home, only committing small numbers on the Continent. Some began appearing late in the Battle of France (German code name Fall Rot). Large numbers of Bf 110s, 32% of those committed, were lost in France, but this disturbing fact was lost in the overall success of the campaign.

|

| Me-110 G NachtJager |

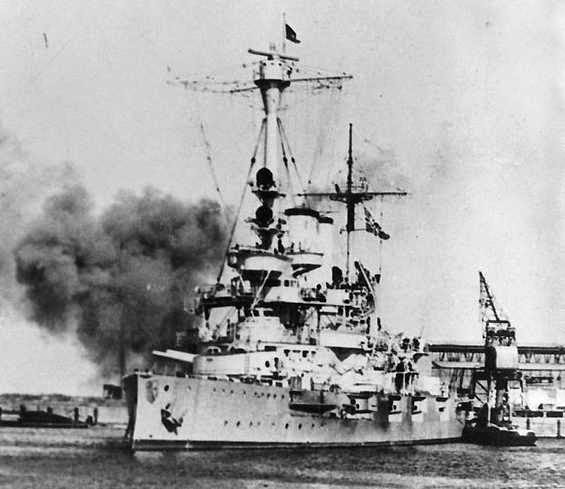

The Bf 110, though, was still considered a front-line fighter as the Battle of Britain began in the summer of 1940. It was far from perfect as a fighter, however. Though fast, it had two problems: it presented a large target; and it lacked nimbleness. The current crop of British fighters had vastly greater armament than their predecessors and could accelerate much faster than the heavy Bf 110. The one advantage that the Bf 110 retained, its long range, did come in handy given the long distances over the English Channel to engage the British. Handled properly, this enabled the Bf 110 to remain in a bomber escort role for a while - it was better than nothing - but the losses started mounting. Goering himself was slow to see the problem develop, and lost his own nephew in a Bf 110 over Portland Harbour. Eventually, the Bf 110s themselves required Bf 109s as escorts. It was a huge come-down for the Zerstörer pilots, who generally were considered the elite of the Luftwaffe.

Things came to a head on 15 August, Adler Tag (Eagle Day), when the Germans mounted their official opening of the Battle of Britain. The Bf 110s flew over Britain as normal, and the Spitfires and Hurricanes were waiting to pounce. After losing 30 Bf 110s in that one day alone, there weren't enough to continue operations, though the Germans undoubtedly would have thrown more into the battle in subsequent days if they had been available.

|

| Me-110 G NachtJager |

The Bf 110 did continue making occasional appearances in the remaining days of the abortive Battle of Britain. They had a great day on 31 August 1940, for instance, shooting down about a dozen Royal Air Force (RAF) fighters, a very creditable performance for three of their own number shot down. Subsequent operations, though, were catastrophic. Overall, the Luftwaffe lost 223 out of the 237 Zerstörers with which they began the one-month campaign, crippling losses which no air force could long sustain no matter how quickly the factories supplied replacements, because each lost plane also meant a lost pilot and a lost gunner.

|

| Me-110 E “Fliegender Haifisch” |

The Bf 110 remained a favorite of many Luftwaffe pilots despite the losses. It was stable and flew a long ways. Rudolph Hess chose one for his Quixotic flight from Augsburg to Scotland on 10 May 1941, its long range making the flight possible. The Bf 110 proved of great use again in the Balkans in spring 1941, though suffering further losses when faced with the few late-model fighters there. Crete in May 1941 was very hard on the Luftwaffe in general, and another dozen Zerstörers failed to return.

|

| Me 110 E nose art |

The Bf 110 continued in service in North Africa through 1941 and 1942, primarily serving as escorts for the Stukas and as Jabos themselves. It was here that the Bf 110 was first used in a night fighter role on 22-23 May 1941. The North African Bf 110s ultimately were withdrawn to Crete in August 1942. There, they served as convoy protection, their range again coming in handy. They also served as anti-bomber fighters, their heavy armament much better suited to attacking occasional bombers than engaging in dog fights with enemy fighters in hot, dusty Africa.

Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, kicked off on June 22, 1941. Bf 110s from ZG 26, Schnellkampfgeschwader 210 (redesignated from Erprobungsgruppe 210) and ZG 76 too part. The Soviet air force was large but had a lot of obsolete models against which the Bf 110 was more than a match. The Bf 110 also came in quite handy in a Jabo role because of its long range and heavy armament. Most kills of enemy aircraft in the early months of the war were on the ground, and the Bf 110 with its heavy armament accounted for many of them. As time went on, though, the Bf 110s were recalled or allowed to dwindle away, because there was a much greater need for them elsewhere that was of higher priority, and at which they were better suited than general fighter/jabo operations on the Eastern Front.

|

| A successfully crash-landed Bf 110 |

The pressing need for the Bf 110 that caused their de facto withdrawal from the Eastern Front was defense against the growing Allied bomber forces. The British were bombing by night and the Americans by day, and the Bf 110 was ideally suited for night-time operations. In the darkness, agility and acceleration were non-factors and opponents couldn't see their large silhouette anyway. As every combatant was to learn during World War II, sometimes cutting edge aircraft were unnecessary in certain roles and even a hindrance: witness the British sinking the Bismarck with biplane carrier aircraft, the Swordfish, and the Russians using ancient biplanes flown by women to harass German bivouacs as the Germans tried to get some rest (the "Night Witches"). The darkness completely eliminated the Bf 110's vulnerabilities and magnified its strengths, such as strong armament, heavy armored protection to protect against bomber gunners, and long range. Plus, and perhaps most importantly of all, they had enough power and empty space to be fitted with advanced radar sets.

|

| Schräge Musik |

The Bf 110's open nose offered plenty of space for the bulky radar equipment of the day and also a dedicated operator for it. This gave the craft a three-man crew, which added to the weight. The Bf 110 also was used during the day, because range-limited Allied fighters often could not accompany the bombers all the way to their distant targets, but then they presented their usual big targets for bomber gunners. As time went on, they were occasionally jumped in that role by Allied dayfighters and suffered catastrophic losses.

At night, though the Bf 110 was at its best. Armed with a variety of exotic weaponry, such as the sloping Schräge Musik (see illustrations above) or four 21 cm (8 in) Werfer-Granate 21 (Wfr.Gr. 21) rocket tubes, the Bf 110 was the scourge of the skies. As the Allied night-time air fleets increased in size, successful deployments at night of Me 109 dayfighters ("Wild Boar") were added (operating by the light of the moon) to the custom-built Bf 110 nightfighters ("Tame Boar") to create a defense in layers. One nightfighter ace, Heinz-Wolfgang Schnaufer, racked up the incredible total of 121 aerial victories (the Luftwaffe instituted a points system during the war in which aircraft were worth more depending upon how many engines they had). The darkness offered a lot of protection, and you could park silently underneath a bomber far above, let loose with your Schräge Musik at your convenience, and then scoot away without anyone seeing you at all. It was a deadly weapon.

|

| Schräge Musik did not protrude far from the cabin. You can barely see them in this picture, but they are right in front of the machine gun. |

In 1944, the twin-engine Me 410 came along, another attempted replacement for the Bf 110. However, Allied fighter superiority was so great that the Me 410 did no better during the day than the Bf 110 did. The Me 410 was slightly faster but even less agile. By April 1944, when the P-51 Mustang started appearing in numbers and escorted bombers the whole way to Berlin, the Zerstörer was finished in a daytime role, and none of its planned replacements could be used then, either. Only the protection of darkness kept it relevant.

British Royal Air Force General Arthur "Bomber" Harris was determined to win the war by completely wiping Germany off the map with his bombers. He instituted mass night attacks that had 500, 1000, 1500, and ultimately 2000 four-engine bomber streams attacking targets. He posed the question himself of whether or not it was realistic for bombers to make any difference in the outcome of the war, and answered his own question by replying, "Well, I say in response that it has never been tried." These were massive raids that left cities in ruins, some over 90% destroyed. The old medieval cities with narrow streets and wooden buildings, he found, burned best. The Bf 110 rose to the defense of the screaming women and children and destroyed some 2751 of Harris' bombers in 1943 alone, a claimed 123 over Hamburg in one night, 1,128 in five months over Berlin beginning in November 1943. However, there were always more bombers coming out of the British factories, using materials shipped in by the endless convoys from America, so the attacks continued to grow in intensity. The Junkers Ju 88 fast bomber was converted to night fighter missions as well, but the Bf 110 was the backbone of the fighter defense. The biggest problem for the Luftwaffe was that the need for air protection against the Americans bombing during the day grew as the years passed, so the Luftwaffe high command took to using night fighters during the day. This did not improve the daytime defense much, but resulted in huge losses to the night fighters. When daytime operation were wound down, the night fighters did much better.

|

| Bf 110 night fighter |

However, it was a losing battle for the Germans. As the ground troops were pushed back, the Allied fighters could roam over Germany at will. The night bomber raids became too densely packed for the night fighters to make much difference - even if they shot down 20 bombers, there were still 2000 left. The Zerstörers continued shooting down bombers to the end, but it was not enough, and ultimately their defense of the night skies failed.

2014