A Silent Tragedy

|

| Sydney crewmen in Alexandria, Egypt, sometime in 1940. Can't wait to get back to Down Under far from the war where it is safe! Source: Royal Australian Navy Sydney Memorial. |

The sinking of HMAS Sydney on or about 19 November 1941 was one of the great tragedies of World War II that has received the least attention. I sometimes see people claim that World War II wasn’t actually a “world” war because “nothing happened in the Indian Ocean.” Well, in fact, quite a bit of combat happened in the Indian Ocean, with the biggest clash of all being between Sydney and German raider Kormoran.

One of the reasons the action has received so little attention outside of Australia is that nobody from Sydney survived to tell the tale and the German survivors weren’t all that keen to talk about it and were in POW camps for five years. Not only did nobody survive Sydney, for the longest time it was believed that not even a single body was recovered. Sydney just disappeared.

That wasn’t terribly unusual during World War II. Of course, it happened quite often with submarines sunk by depth charges, where the men had no chance to escape. Probably the most famous example was U-47, which disappeared in March 1941 with the famous Günther Prien aboard. That was just one example of dozens and dozens of submarines that disappeared with all hands.

|

| HMAS Sydney 1940 in the Mediterranean. Source: Australian War Memorial 301473. |

Submarines may seem like a special case. After all, they’re often caught underwater to begin with. However, it also happened with many, many surface ships, including both naval and commercial ships.

Ships sunk with few survivors included USS Juneau, with only ten survivors out of 697 crewmen, and German heavy battlecruiser Scharnhorst, with 36 survivors out of 1986 crewmen. Destroyer USS Jarvis had no survivors out of 233 crewmen early in the Guadalcanal campaign.

There were literally hundreds of naval vessels sunk during World War II with no survivors. Hundreds of ships. That's right, hundreds of ships with no survivors.

|

| Crewmen of HMAS Sydney at Alexandria, Egypt, 1940. Source: Royal Australian Navy Sydney Memorial. |

So, HMAS Sydney had a lot of company in having none of its 645 men survive. It’s all conjecture, but there are several likely causes for the lack of survivors.

Survival at sea requires you to jump over numerous obstacles. Each one, individually, may not seem like much when we’re reading about it 80 years later, but each obstacle whittles down the number of people who can then try to hurdle the next one. It’s a pretty grim cut-down process.

First, the sinking happened around midnight. Tough to get your bearings in the dark, with no lights in an endless sea. Not easy to spot anything to grab onto.

And, there wouldn’t have been much to grab onto anyway. We’re all familiar with how warships look. What’s not obvious until you think about it is that there isn’t a lot of floatable material on deck. Cruise ships are lined with lifeboats on the “boat deck” - cruisers don’t have boat decks. There will be a launch or two, some rafts, and that’s it.

It’s not like everybody would have been standing around on deck waiting for the right time to jump into the water. They would have been below, fighting fires, manning pumps, trying to get the engines to work.

|

| Sailors of HMAS Sydney while serving in the Mediterranean, 1940. Source: Royal Australian Navy Sydney Memorial. |

When discovered in 2008, Sydney was found to have sunk after its bow snapped off. Since the bow was found near the rest of the vessel, that probably precipitated the final plunge (as with RMS Titanic). The ship then sank vertically, which would have been quite fast. It’s not easy to climb ladders and stairs when they’re horizontal. People normally topside in the superstructure was killed during the battle, so the survivors of the battle are mostly below the waterline - not a good place to be in a sinking ship.

And that ship, your home perhaps for years by now, the place you knew like the back of your hand and could "walk through blindfolded," is now suddenly alien territory. It is trying to kill you, with nothing where you expect it to be. Oh, wait, that corridor isn't there anymore because a shell destroyed it, better go to Plan B! Maybe that corridor you used to walk down in ten seconds is now vertical - hard to climb up steel plating. You have to think through every move - where you used to turn left, which way do you go now to get to the surface, and which exit (that you normally don't use very often) is still going to be above water? - and thinking things over with the sea surging in isn't a good plan.

|

| Able Seaman Thomas Welsby Clark hurdled all the obstacles and made it to carley raft. Having survived a brutal Darwinian cut-down process, this enabled him to wait out endless days and nights with no food or water, waiting for help that never came. Source: Royal Australian Navy via Quadrant Online. |

There aren't a lot of openings to the outside in a cruiser to crawl through. There is a set number of exits with no skylights or anything like that where you might get out to safety. Heavy watertight doors will be closed and they open at funny angles that may be against gravity. Water is coming in at random places from shell and torpedo damage. And the lights have failed and there’s total darkness and things have fallen in your way that you have to crawl over. And you’re exhausted from manning the pumps for hours. "Don't tell me it's impossible, lads, you either get 'er done or we all die." And a dozen other sailors, your mates, are in the same corridor blocking your way as the precious seconds tick by. Some of them are dead or dying, maybe calling out for help - do you stop to aid them?

And getting out of the dying ship is only the beginning. So, a small number of lucky sailors would have found their way topside. Avoid getting pulled under from the suction! They would have been struggling in the water in pitch darkness. The sea undoubtedly was covered in oil, perhaps some of it on fire, which makes swimming difficult. You hear voices of dying men crying out for help or just, well, crying out because they know what's coming next.

|

| Carley floats were stored in out-of-the-way places and designed to float free in the event of a really bad day. Source: Legion Magazine. |

Okay, well, you can handle all that, right? You're out, you watch that dark shadow of the ship slide under a few meters from you, it's nice, warm water because it's summertime Down Under. All's good, you're the lucky one, the clever one, the overachiever who got out! Wasn't so hard! They should have taught those other blokes who didn't get out what's what! At that point, you just tread water and wait for daylight. Look for one of those rafts that you never noticed during your daily routine, what were they called again - oh, sure, carley rafts. With the sun will come the rescuers because that’s what always happens in the movies, right?

Well, the crew of Sydney didn’t get off any distress messages because the Kormoran’s very first salvo destroyed the bridge, killing the bridge crew and likely terminating the radio apparatus. So, nobody even knew that the Sydney had been sunk for five days. A search wasn’t even begun until 24 November and lasted only through 29 November. The men in the water (and there were likely some from Kormoran, too, though miles away from the Sydney men) were probably all dead before the first ship left a harbor or the first plane took off to look for them.

|

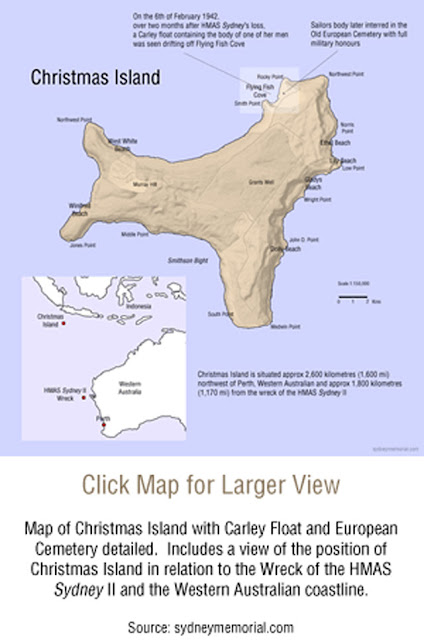

| May of Sydney sinking and where the carley float was found about three months later. |

The men in the water wouldn’t see any rescuers at dawn or at any other time because it’s a big ocean and things get lost there very easily. I’m sure you’ve heard about that Malaysian plane, MH 370, that disappeared in 2014. When someone asked me then how long it would take to find it, I said “never.” I compared it to flying a helicopter over the United States looking for a plane that had crashed but you had only the vaguest notion of in which state it might have happened. “Look in the Midwest first.” Yeah, good luck with that. Incidentally, there are many WWII plane crashes that have never been found, too.

But anyway, the men would have been struggling in the water not just until morning, but for one endless day after another. As far as they were concerned, they would be struggling in the water for eternity, getting thirstier, hungrier, weaker, and more sunburned until they finally just accepted it or drank some water ("it can't be as bad as they say") or drowned in the waves.

Some, injured during the battle, would have succumbed quickly. Sailors fighting fires in the bowels of the ship or in the engine room wouldn’t have been wearing much (it would have been hot as Hades below decks), hence had little protection from the cold at night and the burning sun during the day Water sucks the heat out of you much faster than air. Others would have lasted a day, some two days, maybe a few for longer. But each day would have been another obstacle, and notice what I said above about obstacles. No food, no potable water, no shade from the sun beating down on you… it’s not a pretty picture even if you do somehow make it to a raft.

|

| Wreckage of USS Indianapolis from a National Geographic documentary. Source: Television Business International. |

The experience of the USS Indianapolis in 1945 will give you chills if you read about it. There were many, many men struggling to survive in the water after it was torpedoed just after delivering an atomic bomb for special air mail delivery to Japan. They grouped together, holding onto each other to survive until rescuers came.

And then the sharks came.

So, the number of survivors of the Sydney was dropping constantly for a variety of factors. There’s one more fact that will make the point. The wreck was discovered about 222 km west of Australia. Okay, so maybe some men would have somehow swum to shore or drifted there, right? You know how wreckage always winds up ashore, some of them should have made it. Well, if they were champion endurance swimmers with perfect preparation, perhaps. But there’s one last fact you need to know before you reach that conclusion:

the currents in that part of the Indian Ocean sweep in a counterclockwise circular pattern away from Australia and toward Africa. They head north, then west. Not toward land. Even if you made landfall before making the big left turn toward Africa, it would take months - months - to see land in the distance. And, it's not easy to see land far away when you're bobbing in the water.

That’s why bits of the wreckage of MH 370, which could have crashed within a few miles from the Sydney’s wreck for all we know, are still being found in South Africa and on islands off the African coast. Thousands of nautical miles away. And it took months, even years, to get there.

|

| German raider Kormoran, which sank around the same time as HMAS Sydney after their battle (Federal Archive Image 146-1985-074-27). |

A fair question is how there were 318 survivors of Kormoran’s 399 -man crew but none from Sydney. Well, it was the luck of the draw. The crewmen on the German raider realized early on that their ship - never built to survive gun battles and thus not expected to take punishment from a cruiser and survive - was going to sink. So, they abandoned the ship early on in good order. That apparently wasn’t the case with the crew of Sydney. And things would have been easier for the Germans after the sinking, too. A converted merchantman would have had plenty of stuff lying around that would float and give men something to grab onto to keep themselves from drowning. The Kormoran even had lifeboats, helpful as a part of the disguise of being an Allied merchantman.

Even then, with the Germans being questioned, it wasn't clear what happened. The German survivors didn't see the Sydney sink. They all had different stories based on the bits of information they did know. Among other things, they didn't know the precise position of the battle. And then, the Germans didn't know how long it took Sydney to sink or which direction it went in (south by southeast, it turned out). The currents by then already had five days to work their magic and take the survivors far away from that location in some random direction anyway.

|

| A carley float from HMAS Sydney that didn't save anyone. Source: Naval Historical Society of Australia. |

Days passed with nothing for the survivors to look at but the endless sky. The few sailors nearby that kept you company would have drifted away during the nights, so eventually you were all alone. Hard to spot a single man with no bright clothing or other clear identifiers in the middle of the ocean. Even if you somehow had a flare gun, there aren't a lot of passing ships because you weren't on a freighter on a normal trade route. You were just out there in some random place in the middle of nowhere.

Being adrift after your ship sinks or your plane crashes is one of the worst ways to die. You have plenty of time to think things over and often not a thing you can do to avert the inevitable unless you get lucky and someone happens by and spots your head slightly above the waves.

A passing tanker finding the Germans five days later was the first indication to the authorities that there had even been a battle. Nothing happened in the Indian Ocean during the war, right, so why would there have been a battle? Maybe if the tanker had found Sydney survivors in the water, the losses would have been more even. The Germans got lucky - some even made landfall on their own, in their boats - and the Sydney sailors didn't. Luck of the draw.

This is all just cold, hard reality, and the same thing could happen to any of us at sea.

To show how World War II still haunts the world, just last week - 19 November 2021 - Australia announced that a body found in a carley float near Christmas Island on 6 February 1942 was, as long thought, a certain crewman from Sydney. He was identified using DNA testing of relatives. The sailor, Able Seaman Thomas Welsby Clark, had two shrapnel wounds to his head, one in his left forehead and one above and behind his left ear that destroyed his skull. How he ever made it into a raft is a miracle in itself. Men in the water would have had wounds, too. It's never a pretty sight after a fierce battle.

Even a lucky sailor who somehow made it to a raft couldn’t make it over all the final obstacles. The men in the water had no chance at all.

|

| A carley float in a museum in South Africa. One of these helped one sailor from Sydney die slower. Source: Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net). |

2021