A Controversial Enabler Turned Subversive

|

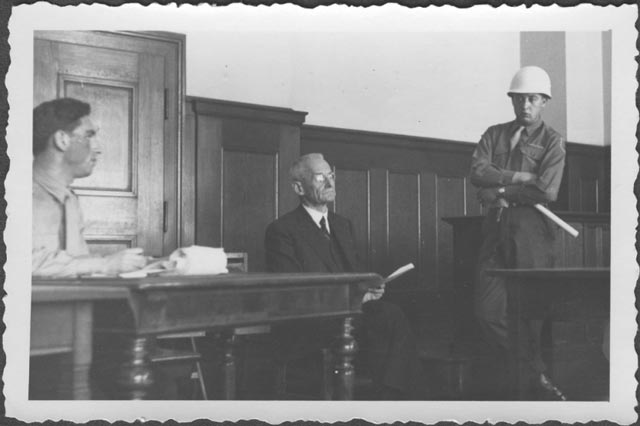

| Franz Halder at Nuremberg. |

Hitler fired Halder just as things were beginning to turn sour for the Wehrmacht. Therefore, he served as a scapegoat for the army's increasing problems on the Eastern Front. Since then, a myth has arisen that the failures that began for Germany at Stalingrad were due to Halder's interference in operations.

|

| Franz Halder with Walther von Brauchitsch on 19 October 1939 (Federal Archive Figure 183-H27722). |

Let's take a close look at what Franz Halder actually did during World War II and see how accurately people view him.

|

| Franz Halder on a diplomatic trip to Finland during the Winter War. |

Franz Halder's Background

Franz Halder was a classic product of the German military system. There was a narrow path to advancement into the upper reaches of the high commander. One had to attend one of a limited number of schools, find a powerful patron, and acquire a certain world-view appropriate to leaders in the army (Heer). Halder checked all the boxes.Franz was born in Würzburg, Franconia, northern Bavaria on 30 June 1884. His father was an officer, the first box that he had to check, as family military history was of critical importance. After enlisting in 1902, he then went to the Bavarian War Academy and graduated in a very timely fashion (considering world events) in 1914, checking off another box. Halder received the Iron Cross 1st Class despite serving primarily in staff roles, checking off a very important box that gave him credibility. He showed enough promise to be retained in the tiny 100,000-man post-war Reichswehr, a highly prized position which assured slow but steady promotions and a steady paycheck.

During his time in the army training department, Halder served under Walther von Brauchitsch. Showing great promise, he became the chief of staff of a military district. Finally, after more than a decade of deskwork, Halder was promoted to generalmajor in October 1934 and given a field command. His command, the 7th Infantry Division, was based in Munich. This was quite fortuitous considering that it was also the home base of Adolf Hitler. This led Halder to meet Hitler in 1937. It also enabled Halder to meet many of the important military men around Hitler.

|

| Ludwig Beck, Chief of Staff of the German Army between 1935 and 1938. Beck is one of the most overlooked figures of World War II - he held no commands but indirectly influenced events (Federal Archive Image 146III-286) |

It might seem unrealistic to state that Halder required "convincing" to take the lead role in the army. However, Halder was leery of taking the position because he agreed to a certain extent with Beck's opposition to the dangerous military adventures Hitler was embarking upon. Taking the position required convincing Beck that he deserved it, which wasn't easy. One complication was that Beck resented Halder because Halder had insisted on hiring his own cronies rather than retain Beck's people when he became Oberquartiermeister.

|

| Ludwig Beck saw a kindred spirit in Franz Halder. |

The Beck/Halder relationship illustrated one of the weaknesses of the rigid Wehrmacht hierarchy. Promotions often were based as much or more on cronyism than on competence. The theory was that good officers would promote others like them. Thus, things generally would work out well. However, when a disaffected officer was in a position to influence promotions, like Beck, he could advance other unhappy officers just like him. This was the case with Beck and Halder. Such situations created cells of hidden power that opposed the orders of their superiors. Beck displayed his true feelings much later when he became a key player in a series of attempts to assassinate Hitler. He perished during the last one on 20 July 1944. Halder, as we shall see, followed Beck in that area as well, but we are getting ahead of ourselves.

|

| Field Marshal von Brauchitsch spent endless hours poring over maps with Hitler - sparing Halder the chore until about two months after this photo. Nobody who did this lasted very long, for Hitler blamed everyone around him when things went wrong. The others around the table include Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel (nearest) and General (later Field Marshal) Friedrich Paulus (Federal Archive Bild 101I-771-0366-02A). |

So, as chief of staff, Halder was in a comfortable position where everybody reported to him and he basically only had to report to his old friend Walther. He was at the nerve center of military plans and estimates flowing up to him from below, of orders flowing down from the Fuhrer Headquarters, and of the multitude of reports coming in straight from the front. Nobody on the Eastern Front knew more about the true state of operations than Halder, and it wore on him. He served as the army's true communication center, almost like a telephone operator, plugging away despite his growing dissatisfaction with how the war was being run.

Above everything else, Halder's greatest talent was the pushing of a lot of papers. His detailed daily diary entries, made despite an increasing avalanche of information passing through his hands, shows a fanatical devotion to routine. In those days, one had to sit down a secretary who would take the notes down by hand. This was not a quick process. The multitude of diary entries also suggested that Halder prioritized routine matters which weren't of the greatest importance to the war effort or even his own development as an officer. However, that did not matter. With the Heer growing rapidly, there was an increasing flow of papers to push, and Halder was just the man for the job. The Chief of Staff position was the ideal slot for Franz Halder - in peacetime.

|

| Franz Halder (right) with Field Marshal Wilhelm List, probably during the summer of 1942. |

Halder's Role in OKH

Franz Halder's chief role during peacetime was to oversee the planning of potential operations and ensure the smooth running of the army's administration. Several generals (such as Wilhelm Keitel) made their careers by being the best paper-pushers in the building, and Halder was one of them. While a competent staff officer, Halder gained no operational experience while sitting in his office. Despite his Iron Cross, there is no record of him leading any troops in battle. He fairly recently had led an infantry division, but only during peacetime when such positions mostly involved the type of paper-pushing at which Halder excelled.During the war, Halder's role changed. The Chief of Staff basically served as a relay between the top field commander (primarily Army Group commanders but also some leading generals such as Heinz Guderian) and Hitler. As the pace of the war picked up following the invasion of the Soviet Union, Halder became the key “point man.” In baseball terms, Hitler was the owner/manager (a very active and meddling manager), while Halder was the general manager. Never on the field, Halder worked behind the scenes making all the arrangements for those actually ordering and fighting the battles.

To continue the baseball metaphor, talking about Halder in the abstract is like discussing a home run hitter without actually mentioning specific homers. Halder participated in many critical decisions, some of which he passed along as ordered and some of which he fought against with mixed success. There were instances where Halder displayed good military sense and others where he did not. Let me give some concrete examples of Halder’s military judgment.

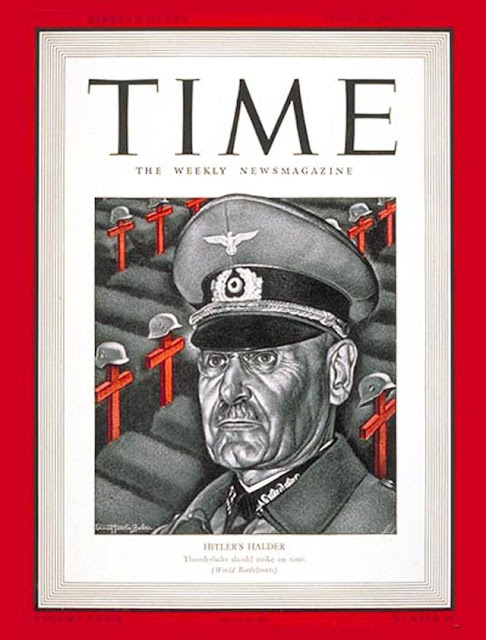

|

| Franz Halder on the cover of Time magazine, 29 June 1942. Strangely, these cover illustrations of German generals usually occurred just prior to or just after their dismissal (Ernest Hamlin Baker). |

On 24 May 1940, Hitler grew worried that his panzers were advancing too far ahead of the infantry as the British retreated to Dunkirk. He peremptorily ordered them to stop. Halder joined General von Brauchitsch in protesting this order, believing that General Guderian’s panzers could reach the sea and disrupt the British evacuation. However, Hitler muttered about the “Flanders marshes” that he had experienced during his service in World War I and the panzers were halted for two critical days. This is considered one of the great blunders of World War II.

This situation, where the professionals all realized that Hitler had made a mistake but could not change his mind, became typical.

3 July 1940, he ordered his staff to draw up plans as a “desk exercise” that, after many revisions, became Operation Barbarossa. This initial invasion plan (Operations Draft East, also called the "Marcks Plan" after the staff officer, General Erich Marcks, who prepared it) was ready for review on 5 August 1940. Halder thus got the planning process off to an early start because of his ability to look ahead. Hitler himself apparently did not reach the same conclusion about the USSR until the very end of July 1940. Unfortunately, Halder shared everyone else’s extravagant optimism about a campaign in Russia and viewed the notorious “Arkhangelsk-Astrakhan line (the "A-A Line") worked up by Marcks as a reasonable objective for a summer campaign. Perhaps this was due to Halder's own lack of combat experience. This flaw got the planning process off to an unrealistic start which lasted through the invasion itself. It is important to note that Halder had no input on the decision to invade the USSR.

There are other examples of Halder's perceptive vision. He was among the group of generals who viewed Moscow as the most important objective while Hitler focused instead on Leningrad and Ukraine, for instance. The point is that Halder was not some “loose cannon” who made poor decisions or just followed other people's lead. He was a hard-working, conscientious staff officer who may not have been very imaginative, but did his job well. He even sometimes ignored Hitler’s decisions in subtle ways, which infuriated the Fuhrer, but when he did, he was usually proven right.

For instance, Halder drafted, or at least edited, the infamous "Guidelines for the Conduct of the Troops in Russia" that was sent to the troops on 19 May 1941. This is another in a string of highly questionable orders covering the conduct of soldiers during Operation Barbarossa. It states in part that the invasion:

demands a ruthless and strenuous crackdown on Bolshevik agitators, irregulars, saboteurs and Jews, and the complete elimination of both active and passive resistance. The Asiatic soldiers, in particular, are inscrutable, unpredictable, underhand and unfeeling."Jews are singled out throughout the Guidelines for special treatment, and no doubt is left that this includes their elimination. As with many other OKH orders issued during this period, the Guidelines are highly illegal under any remotely reasonable interpretation. Halder was never prosecuted for these types of orders issued through his office, however.

|

| Franz Halder inspects the White Guard of Finland on June 30, 1939. |

Moral faults aside, Halder’s failings primarily centered around his passivity and lack of real battlefield experience. He was much too trusting of the flawed work that his staff produced, particularly during the critical days of Operation Barbarossa. For instance, on 26 July 1941, he wrote portentously in his war diary, "The mass of the operationally effective Russian Army has been destroyed." This, of course, was far from the truth. Such over-optimistic conclusions recur repeatedly in his war diary, intermixed with expressions of doom and gloom when the Red Army fought back.

|

| Romanian Marshal Ion Antonescu and Franz Halder during a state visit in March 1942. |

So, Halder received all the reports of casualties and troop strengths, all the phone calls from the generals at the front, all the voluminous estimates of enemy dispositions. He was a font of useless information and eager to share it with the true decisionmakers. He himself, however, had no way to effectively use that information. From time to time he inserted himself into decisions, usually with good effects, but far more often, he just served as a sounding board and “held the generals’ hands.” Halder’s most common job was just to act as a relay between Hitler and the generals at the front. It was extremely frustrating for Halder, and you can watch the frustration grow day by day as you read his war diary. But, the key decisions were not his to make.

|

| Adolf Hitler studies an Eastern Front map with Field Marshal Walter Von Brauchitsch (left), the German commander in chief, and OKH Chief of Staff Col. General Franz Halder (right) on August 7, 1941. |

Halder's Downfall

As noted above, things ran smoothly for Halder as long as there was a buffer between him and Hitler. Up until late 1941, Brauchitsch attended the Fuhrer conferences daily. Halder, however, only appeared, on average, twice a month. Thus, Hitler had little idea what Halder, the "stats guy," was really all about.All of this changed in December 1941. The Soviet counteroffensive at Moscow caused a lot of German casualties, and one of them was Brauchitsch, Halder's shield against Hitler. The Fuhrer fired Brauchitsch on 19 December 1941 and assumed "this little matter of operational command," as he put it. In actuality, he had been exercising direct command for well over a year already. Suddenly, Halder was the point man himself and had to attend the daily Fuhrer headquarters briefings rather than remaining comfortably ensconced in his office while Brauchitsch faced Hitler and his wildly erratic moods and changes of strategy.

It is the same in any business: coming into close contact with the "big boss" can be good for one's career if you get on well with him. However, it also can go the other way in a hurry. Halder had never particularly liked Hitler and, as expressed in his candid war diaries, felt that Hitler was an amateur playing a dangerous game. Halder, however, was quite shrewd. He hid his disdain for the Fuhrer under a mask of professionalism. To the astonishment of those who knew the real situation, he also began to blame the departed Brauchitsch for the difficulties the Heer now faced outside Moscow. This pleased Hitler, as it absolved him of all blame, but the stage was set for a reckoning. It came as the critical 1942 summer campaign in Ukraine, Case Blue, begun with sky-high hopes, became stuck in the ruins of Stalingrad.

|

| A signed postcard showing Field Marshal von Brauchitsch (left) and Field Marshal von Bock. German generals were celebrities in their day. |

Von Bock's dismissal and replacement left Halder more vulnerable than ever before. Now there were no more scapegoats left in the Army Group South sector. If the problems were not the execution of Case Blue in the field by von Bock, perhaps it was the fault of the plan... Halder's plan. So, Halder was the next victim in line. With the Sixth Army reduced to battling through apartment blocks in Stalingrad and winter closing in, Hitler brusquely fired Halder during a routine daily Fuhrer conference. Halder was forced to leave the map room alone. He was shunned by the other members of Hitler's entourage with only the assistance of Hitler's Army Adjutant Gerhard Engel (who later wrote about the incident in his memoir "At the Heart of the Reich: The Secret Diary of Hitler's Army Adjutant") until he could pack his bags and leave for home.

|

| Franz Halder being interrogated at Nuremberg (United States Holocaust Museum). |

|

| Franz Halder not long before his death in 1972. |

Conclusion

If this article presents a mixed picture, that is intentional. There was nothing extraordinary about Franz Halder. He followed the standard German military path, met the right people, and was in the right place at the right time. There was a common feeling in the Wehrmacht that generals of the Artillery were good strategic thinkers but somewhat behind the cutting edge of military thought, and Halder fit that mold. He made his best effort to understand and encourage imaginative thinkers like Guderian, but he primarily was the recipient and transmitter of ideas, not the creator of new ones.It goes without saying that Halder had to be bright and agreeable to take advantage of his opportunities. He certainly filled his role with great energy and some insights about military strategy. However, Halder did not earn his promotions by winning battles or planning campaigns. Instead, despite his attention to detail, occasional bursts of true insight, and intense concentration on operations and the people running them, Franz Halder still was a classic staff paper-pusher, of the type that Hitler would later disparage as a "swivel-chair officer." Halder's work product thus affected Hitler's own view of the war with dismal results.

However, to focus on Halder as a weak link in the Axis war situation is to miss the big picture. Tactics did not lose the war for Germany. The German generals were excellent tacticians, probably the best of the war, and did not need much guidance. The big strategic decisions that decided World War II - Germany invading the Soviet Union and declaring war on the United States, Japan's attack upon the United States - were completely outside of Halder’s control. These are what lost the war for the Axis, not a paper-pushing general far behind the lines. Those decisions turned World War II into the war of the factories, and Germany was always going to lose that kind of war. Halder did a good, maybe even excellent, job, but he had no impact whatsoever on the outcome of World War II.

2020