The names of the top German generals of World War II include a familiar litany of name: Rommel, Manstein, Rundstedt and Guderian always pop up. Occasionally, you will see Model, Kesselring, and a few other well-worn names added for variety. One general who almost never gets mentioned - he is barely mentioned in Corelli Barnett's classic "Hitler's Generals" (Grove Press 1989) - but may have been more effective for the Axis war effort than any of the above was

Hans-Valentin Hube. Known throughout the Wehrmacht as the "one-armed Panzer General," Hans-Valentin Hube is my candidate for the

top German general of World War II.

Let's learn a little more about this overlooked master tactician.

Hans Hube's Background

Hans Hube was born on 29 October 1890, at Naumburg a der Saale (on the Saale River), the German Empire. This birth date placed Hans Hube squarely within the "sweet spot" for top German World War II generals, almost all of whom were born between 1875 (Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt) and 1891 (Erwin Rommel and Walter Model).

Naumburg was a garrison town not far from Leipzig. He followed the well-worn path of young men from his area and enlisted as an officer cadet (Fahnenjunker) on 27 February 1909. He advanced quickly and soon was promoted to Leutnant (Lieutenant J.G.) in the 26 Infantry Regiment. World War I began a few years later, and the 26th took place in the First Battle of the Marne and subsequent trench warfare.

The end of the line for many World War I soldiers was the Battle of Verdun, and it almost was for Hans Hube, too. He was wounded in General Erich Georg Anton von Falkenhayn's "mincing machine" and had his arm amputated. Hube repeatedly requested reassignment despite his injury, and ultimately was promoted to captain during the war.

|

| Major Hyazinth von Strachwitz, Colonel Rudolf Sieckenius, and General Hans Hube left to right. |

There were a lot of disabled soldiers, and only 100,000 slots permitted to the Reichsheer (German army) by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. The spots were highly coveted for their steady employment during tough post-war times, and Hube snagged one despite having lost his arm. Reportedly, Hube was the only one-armed captain in the entire Reichswehr (German military). Hube rose slowly up the command chain, being promoted to major in 1929 and lieutenant colonel on 1 June 1934.

|

| Hube with a subordinate. |

The Germans had lagged badly in panzer development during World War I. However, they had seen how effective Allied tanks were and worked hard to remedy that failing and turn it into a strength. In 1934, Hube took command of an experimental motorized infantry battalion. He handled the unit well in maneuvers, and this led to the creation of the first panzer division in 1936. As a reward, Hube was appointed commander at Doberitz, the large infantry school near Berlin. He then took command of the Olympic village beginning on 1 October 1935 (adjacent to Doberitz), taking responsibility for security and the accommodations themselves, which received favorable reviews. This brought Hube into contact with Adolf Hitler, who took a personal interest in Olympic preparations. Due to his good job at the Olympics, Hube received a promotion to full colonel on 1 August 1936.

|

| Hube while commanding the 16th Panzer Division (1. Panzer-Armee). Hube is standing on a Panzer III during the opening phase of Operation Barbarossa in July 1941. Note the commander's banner on the left of Hube's panzer - at this stage of the war, Panzer III's were worthy of a Division Commander. Incidentally, this shot must have been well behind the front lines, since the tank has a row of gas cans perched on the turret. |

Hube continued training cadets at Doberitz until the outbreak of the war, introducing courses in motorized infantry. As he had during World War I, he petitioned the army (the Heer) personnel office. In October, as the campaign for Poland was winding down, he became commander of the 3rd Infantry Regiment of the 21st Infantry Division. However, Hube was unhappy with the 21st because it was a secondary, static unit slated for use against the French Maginot line rather than in fluid mobile warfare. Once again, Hube petitioned the personnel office, and once again they rewarded him with a staff appointment to Colonel General Fedor von Bock's Army Group B. This soon led to further promotion, to command of the 16th Infantry Division in Belgium.

|

| A rare photo of Hube which indicates his missing arm. |

The 16th Division was perfect for Hube because the army high command (OKH, Oberkommando des Heer) had it on the list for conversion to a panzer unit and already had been partially motorized. Hube was in command for the capture of Mont Damion on 22-23 May and received a promotion to major general on 1 June 1940. After the Battle of France, Hube took his division to Muenster for full conversion to motorization. After that, the 16th moved to Bulgaria to serve as a reserve for Colonel General Ewald von Kleist's 1st Panzer Group, participating in the occupation of Belgrade. After that, along with many other Wehrmacht formations, the 16th moved to Silesia in preparation for Operation Barbarossa.

Hans Hube in Russia

Hans Hube led the 16th Panzer Division in the southern prong of the invasion of Russia. It became one of the first Wehrmacht units to breach the Stalin Line. The 16th completed the encirclement of Kyiv on 14-15 September 1941, linking up with the 5th Panzer Division. Even before the 667,000 prisoners could be counted, the 16th continued heading east toward Rostov, participating in the capture of that city but also the unexpected withdrawal to the Mius River (which cost General von Rundstedt his command of Army Group South). Hube helped hold the line there even as the German forces to the north suffered one calamity after another during the Soviet counterattack.

|

| Generalleutnant Hube while Commander of the 16th Panzer Division. He is with Generaloberst Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, head of Luftflotte 4 on the outskirts of Stalingrad, August 23, 1942. This was the day that the Luftwaffe launched its first concentrated attack on Stalingrad, causing tremendous damage and essentially opening the campaign for the city. |

Hube was getting noticed. He received the Knight's Cross on 17 August 1941, the Oak Leaves on 21 January 1942, and a promotion to lieutenant general on 1 April 1942. When the Soviets mounted their ill-fated offensive against Kharkiv in May 1942, Hube's men went into action. As part of Ewald von Kleist's 1st Panzer Army, the 16th completed a vital linkup west of the Donets and south of Kharkiv that led to the encirclement of huge numbers of Soviet troops. This "Bacaklesa Encirclement" led to the capture of over 100,000 Soviet troops and blew a huge hole in the southern part of the Soviet line.

|

| Hube talking with Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz von Groß-Zauche und Camminetz (mustache). I don't have a date for this picture, but it likely was during the first phase of the battle for Stalingrad, because Camminetz was wounded on 13 October 1942 and sent to Germany to recuperate. |

The 16th Division headed east along with the rest of Army Group South. The XIVth Panzer Corps (General Gustav von Wietersheim), of which the 16th was a part, scored one of the biggest successes of the Stalingrad campaign when it broke through Soviet lines and reached the Volga ahead of the rest of General von Paulus' Sixth Army at the end of August 1942. The XIVth was overextended, however, and von Wietersheim prudently counseled withdrawal from the river until stronger forces could be brought forward. The OKH, via General Paulus, quickly cashiered Witersheim ("called away to another assignment") on 16 September 1942, and Hube - who, somewhat ironically, agreed completely with von Wietersheim - replaced von Wietersheim in command of the XIV Panzer Corps.

|

| Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring with Hube, Italy, November 1943. |

Hube also made a racket with his higher-ups as commander of the corps, complaining about the same things that von Wietersheim had. However, while it was a very close thing, the corps survived and formed the bulwark in the north for the remainder of the battle of Stalingrad. OKH promoted Hube to general of panzer troops on 1 October 1942, likely because he had become a Hitler favorite due to his string of successes. The XIVth Panzer Corps, a mobile unit, then got bogged down in defensive warfare along with the rest of the Sixth Army. This unfortunate situation was notably exacerbated when the Soviet Uranus Offensive began on 19 November 1942. The Stalingrad forces - including the XIVth Panzers - were encircled on 23 November. Hube flew out of the pocket on 26 December 1942 to confer with Hitler, who promised reinforcements. After Hitler conferred the Oak Leaves on Hube on 29 December, Hube took a brief vacation and then flew back to his command in Stalingrad on 7-9 January 1943. However, the Soviets launched another offensive on 10 January, and the 6th Army defenses crumbled. The XIVth Panzer Corps remained a bulwark in the north, but the pocket was compressed by the Soviets moving in from the west.

|

| Hube awards Lieutenant-Colonel of the General Staff Bern von Baer with the Knight's Cross, February 1944. |

It is at this decisive moment when the legend of Hans Hube truly begins. Hitler, sitting at his command headquarters, reviewed his options at Stalingrad. He noted that an unnamed soldier trapped there privately had given a summary of the Stalingrad commanders (all mail from Stalingrad was confiscated, reviewed by military intelligence, and not released to the public for many years). Basically, the soldier wrote off everyone as useless ("should be shot") - except for Hube, who he called "

Der Mensch" (the Man). On 16 January 1943, Hitler ordered Hube to report to Berlin immediately for reassignment. The Soviets already had captured one of Stalingrad's two airfields, and the other was in peril, but there were still a few flights out. Hube resisted, saying that he wanted to stay with his men whom he had led into such a situation, but on 18 January a special

Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor transport plane landed at Gumrak airfield. Keeping the desperate German soldiers at the airfield away, the SS men on the plane took Hube (and his aides, Colonel Thunert, Lt. Colonel Eysen, Colonel Walter Muller and one other man) under gunpoint to the plane. The plane flew out, barely making it back to German lines after being hit by ground fire. It was one of the last planes to make it out of the pocket (cauldron). Stalingrad fell completely in early February, but the calamity there for the Wehrmacht was unavoidable and obvious long before that.

|

| Hans-Valentin Hube and Nikolaus von Vormann. |

Hans Hube in Sicily

Back in Germany, Hube and the aides with whom he had flown out rebuilt a new XIVth Panzer Corps. After a short stint in Ukraine with his headquarters - which had few assigned troops, and basically just organized formations heading further east - Hube received new orders: head to Rome. There, his headquarters studied the terrain, visited Sicily briefly, and wound up near Naples in command of three divisions operating further south. Hube received orders from General Alfred Jodl, chief of operations at the military high command (OKW), as follows:

The vital factor is under no circumstances to incur the loss of your three divisions. At the very minimum, our valuable human material must be saved.

This was a radical departure from the OKW attitude at Stalingrad, and the order puts Hube's next success in context.

On 10 July 1943, the Allies based in North Africa invaded Sicily. The Italians had heavy forces there, but they were poorly trained, not motivated, and some actually helped the Allied unload their equipment on the beaches. Some Italian units did fight hard - armored units at Gela Beach put a real scare into the Americans landing under General George S. Patton - but the only men really fighting hard were the three German units. Hube arrived in Sicily in mid-July as the Axis forces were being pushed back from the beaches. While official histories invariably state that Sicily was under the command of Italian General Vittorio Ambrosio throughout the campaign, in actual fact, from the moment that he arrived on the island, Hans Hube was in complete command.

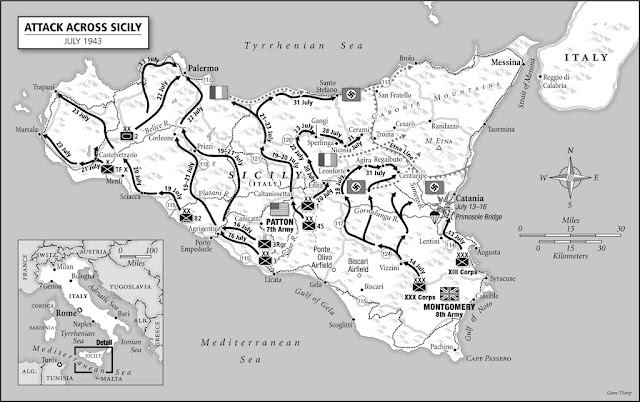

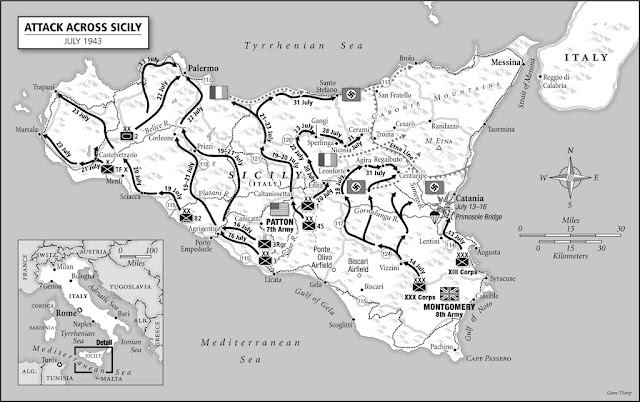

Hube sized up the situation quickly. Sicily is in the shape of a triangle, with one end next to the Italian mainland. This point near Italy - the port of Messina - was the key to the entire island, because whoever controlled it also had command of passage to the mainland. The narrowing approach to Messina also compressed the defense, allowing the Germans to take out formations as the battle proceeded and send them back to the mainland in sequence. This all required a great deal of planning and relied upon very unreliable ferries, but the Germans - Hube - pulled it off. A lesser general would have tried to please Hitler by trying to hold Palermo and other "prestigious" points in the west - but Hube was smarter than that. He stayed in the northwest just long enough to force the American troops to move there

en masse, then quickly pivoted back toward the east - forcing the Americans to fight tooth-and-nail along the entire north coast. Basically, Hube led the Americans on a wild goose chase in the wrong direction while his real objective was Messina in the east all along.

|

| The tactical situation in Sicily. Mount Etna in the northeast divides the approaches to the critical port of Messina in two. This simple fact, along with the narrowing approach to Messina, formed the foundation of Hans Hube's strategy. |

Hube then ordered a delaying strategy wherein his forces fanatically held off the British on the "short road to Messina" in the south at Catania, while grudgingly giving up western Sicily around Palermo to the Americans under Patton. Hube's defense was aided by Mount Etna, which divided the approaches to Messina so that the British and Americans could not link up. Thus, three separate campaigns developed in Sicily: the Americans advancing east along the north coast, the British advancing north past Augusta and Catania along the east coast, and the Germans under Hube retreating in good order east to Messina without allowing themselves to be trapped. All three campaigns succeeded to varying degrees, with Hube's being the only one that beat reasonable expectations.

|

| The Straits of Messina, toward the Italian mainland. While it does not appear very far across, much smaller bodies of water had led to ruin for German forces in the past (Courtesy Rome Alive Again). |

While the Allies conquered Sicily, it took them six weeks - much longer than initially expected - and Hube wound up evacuating his entire command (60,000+ German troops) back to the Italian mainland in Operation Lehrgang. Through very judicious planning, involving precise timetables and relying upon the "Anglo Saxon habit of lunch breaks" (as one participant recalled) during which Allied airplanes disappeared from the skies, the evacuation succeeded beyond all reasonable expectations. Troops would fire their last shots, then walk directly to waiting ferries and be on the mainland, fully intact and armed, within a couple of hours. Hube (and, let's give proper credit, evacuation coordinators Colonel Ernst-Guenter Baade and Commander (Fregattenkapitaen) Baron Gustav von Liebenstein) even evacuated all of their heavy equipment, leaving behind only some railroad cars. In addition, about 100,000 Italian troops escaped, along with

their equipment - which the German troops on the mainland quickly "requisitioned."

|

| Among Hans Hube's tactical decisions, one of his most efficient was blowing the many bridges on the road toward Messina along the northern coast of Sicily. Here, on 13 August 1943, General Lucian Truscott becomes the first to cross the famous bridge that was "hung in the sky" by the 10th Engineer Battalion of the 3rd Infantry Division at Cape Calavà. Hube also made very liberal use of minefields, which greatly slowed down the Allies. Good strategy never neglects the little things, which often decides matters. |

The evacuation featured perhaps the first "roll-on-roll-off" technique in military history, where, rather than have porters unload trucks at the port, the trucks themselves were ferried over, fully loaded. This saved immense amounts of effort and, more importantly under the circumstances, time. Operation Lehrgang, which concluded on 22 August 1943, made the later successful defense of southern Italy at the Gustav Line (aka the Winter Line, centered at Monte Cassino) possible. Considering that the US 7th Army had 217,000 men on Sicily, and the British an additional 250,000 troops, Operation Lehrgang was an astounding evacuation success, achieved in the teeth of absolute Allied domination of the sea and air.

Hans Hube Back In Russia

Hans Hube now had two hugely successful commands under his belt - the brilliant advance on Stalingrad and the efficient defense of Sicily - under his belt, but he was far from through. After briefly commanding his rescued troops from Sicily around Salerno - another efficient delaying operation against Allied Operation Avalanche, the invasion of mainland Italy - Hube returned to Germany to take command of the Fuehrer Reserve OKH. This was simply a waiting room for Hube, however, and on 23 October 1943, he was named commander of the 1st Panzer Army (officially assuming command in February 1944). By this time, the Wehrmacht forces in the USSR were being forced back steadily, and this created numerous cauldrons. One of these pockets of trapped German troops, the so-called Korsun-Cherkasy Pocket, required desperate relief efforts. Hube managed to slice his III Panzerkorps close enough to the pocket against fantastic Soviet resistance for many of the trapped Germans to mistake (how many is hotly debated, but likely around 30,000 men escaped). It was another brilliant success.

However, saving the men in the Korsun-Cherkasy Pocket required Hube to keep his main forces further east than was prudent, given the waves of Soviet troops heading west. Some of the Soviet forces under Marshal Zhukov encircled Hube's own 1st Panzer Army near Kamenets-Podolsky. The stage was set for another Stalingrad, as Hitler wanted Hube to stay where he was until relieved by German troops coming east - something that Hube knew was impossible. He counseled heading south, while army group commander Field Marshal Erich von Manstein favored heading due west. Ultimately, Hitler gave in and authorized a breakout to the west.

This led to perhaps Hans Hube's greatest victory of all. He created a new type of formation - a "mobile pocket" - which concentrated its armor along the line of advance and strong infantry formations serving as a rear guard. Hube's men struggled through the mud of the Rasputitsa (the spring thaw) from 27 March until 15 April 1944, crossing several rivers. They reached the German lines intact. Hans Hube had saved an entire panzer army, without which the German defenses in the east certainly would have crumbled much sooner than they actually did. A defeat there, with the destruction or capture of one of the largest formations left to the Wehrmacht, would be much better known - but sometimes victories get less attention than the disasters.

Death of General Hube

Hans Hube now had achieved outstanding successes in the initial invasion of Russia, the defense of and evacuation from Sicily, and during the withdrawal from Ukraine. Very few soldiers in history have demonstrated such versatility. He had justified his position as a Hitler favorite - something not everyone in a similar position managed to pull off. Hitler decided to recognize Hube once again. On April 20, 1944, Hube left the front lines and flew to Berlin. He was there to receive the Diamonds to the Knight's Cross and to receive his promotion to Generaloberst. Significantly, this was Hitler's birthday, always a huge event in the Reich, and the fact that Hube was invited on that day was an indication of respect.

|

| Hitler personally awards Hube the Diamonds to the Knight's Cross. This was the reason for the flight that killed General Hube. |

After receiving the award, Hube got back on his Heinkel He 111 to return to the front. Shortly after stopping at Ainring airstrip in Salzburg on 21 April 1944, the plane crashed into the mountains. Everybody aboard perished, and the only identifiable remains of Hube was his replacement arm made of black metal. Parenthetically, Field Marshals were forbidden from flying precisely because of the risk of accident, but, despite rumors that Hube was in line to command his army group, he was not yet at that rank. Thus, Hube was still able to fly and flew to his death. There were rumors that the plane crashed due to sabotage, but there is no evidence of that, and accidents do happen.

|

| Hube's funeral. In front, Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring flanking an unidentified family member. Beyond them are Erhard Milch and Günther von Kluge. In the next row, from right to left: Rudolf Schmundt, Julius Schaub, Karl Jesko von Puttkamer, and Friedrich Fromm. |

Hans-Valentin Hube received a state funeral, which by that time was far from unusual. The notable aspect of the funeral was that Hitler attended, which by that point in the war was not common. In fact, this was among the last funerals Hitler attended, another mark of respect.

|

| Hube's funeral on 26 April 1944. Front row: Generalfeldmarschall Hans-Günther von Kluge, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, Großadmiral Karl Dönitz and Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel. In the next row: between Kluge and Himmler is General der Infanterie Joachim von Kortzfleisch, with Generaloberst Hermann Hoth between Dönitz and Keitel (head bowed) (Ang, Federal Archives). |

Hube was - is - buried at the Invalidenfriedhof in Berlin. The original tombstone was replaced in 2000, but the grave remains undisturbed and may be visited.

Conclusion

At a minimum, I hope to have convinced you that the name Hans-Valentin Hube is worth knowing in the context of World War II. Everyone can argue about who was the top general of World War II (who I don't think was a German, but that's another story). However, hopefully, you will acknowledge that Hans Hube was an extremely talented general who merits study and at least consideration for that accolade.

It is easy to dismiss all German generals as evil because they served the Third Reich and its well-known vicious ends. It is perfectly rational to do so about Hans Hube as well. Nobody expects you to honor one of Hitler's minions. However, consider that there is no evidence that Hube knew anything about slave labor or extermination camps or the many atrocities of the war - he was just a soldier. Not only was he a soldier, but he was one of the top generals of the entire conflict. Had he survived the war, Hube might be much better known today, but his record of military achievement remains untarnished for those who choose to understand it.

|

| Hans Hube. |

2020