Green Devils

|

| This picture is from Der Adler (The Eagle) (published 16 August 1940). It shows the Fallschirmjäger attack on Waalhaven (Rotterdam Airport) on 10 May 1940. |

Fallschirmjäger were German airborne troops. More than any other force, they were the creation of one man, Major General Kurt Student. The commander of a fighter squadron during World War I, Student worked between the wars in the Fliegerzentrale, an unofficial (because it was prohibited) precursor of the Luftwaffe.

|

| General Kurt Student inspecting Fallschirmjäger Regiment 3, Sicily August 1943. |

Kurt Student was promoted to Colonel in August 1935 and made commander of the Luftwaffe Test Center for Flying Equipment at Rechlin air base north of Berlin.

|

| The first Fallschirmjäger working on technique at an exhibition during the 1936 Olympics. It must have been difficult to swim with those heavy packs. |

After some preliminary experimenting with the new troops, the Luftwaffe opened a parachute school at Stendal in 1937. In early 1938, Hitler and Air Minister Hermann Goering, perhaps due to Soviet work in the field, decided to form a paratroop command in 7. Fliegerdivision (7th Air Division) at Muenster.

|

| Fallschirmjäger training in the gym. |

It was all cutting edge stuff - the United States, for instance, did not even consider forming a paratrooper unit until 1940.

|

| Fallschirmjäger with MP.38 submachine gun. |

Kurt Student started with a blank slate. While there were some paratroopers training in the Soviet Union, virtually no other country had any, at least as an independent force (the US began officially training paratroopers around 1940). Kurt Student worked with subordinate Heinrich Trettner to come up with something.

For starters, they needed a plane, and the Junkers Ju 52 was available. It was slow and had a large weight capacity, which is necessary for paratroopers. Unfortunately, the Ju 52 also was very vulnerable to both ground- and air-attack, but that became a problem only later.

|

| Alighting at Crete. |

Fallschirmjäger were airborne troops, but that doesn't just mean parachute soldiers. Along with the 7th Parachute Division, Student formed the 22nd Division for troops to be landed in gliders.

|

| Fallschirmjägern in a DFS-230 glider. |

The DFS 230 was the largest glider that could be towed by the Ju 52, so it was the best choice. Each glider could carry 9 fully equipped Fallschirmjäger in addition to the pilot, who of course was a trained Fallschirmjäger as well.

|

| Out we go! |

Kurt Student was just able to form and train the Fallschirmjäger by the outbreak of the war. The first mass drop by the 1st Parachute Regiment was in the summer of 1939. However, the Fallschirmjäger were not used in Poland because they were not needed for any special objectives. So, training continued.

In addition, the Luftwaffe and Heer (army) both laid some claim to the Fallschirmjäger and thus credit for their successes would be dispersed - leading the Luftwaffe command to prefer to focus on other areas rather than share any credit.

|

| Parachuting was not well-developed at this point. The parachutist had no control over the descent and dangled like a doll from the attachment on his back. The parachutist wore special cushioned boots and other special items to cushion the fall, but many injuries resulted from the act of jumping - putting aside enemy fire. |

Kurt Student added two more regiments to the 1st during the Polish campaign, along with the 16th Infantry Regiment and support troops. By early 1940, with bigger objectives coming into view, there was no further reason to keep the Fallschirmjäger in reserve. However, they needed to prove themselves in some way - and that way came along in April 1940.

Battle of Dombås

At the urging of Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, Hitler decided during the winter of 1939/40 to seize Denmark and Norway. The invasion, Operation Weserübung ("Weser Exercise"), began on 9 April 1940 and went fairly smoothly. Most of the Fallschirmjäger participated on the first day of the invasion, though not as a discrete force. Copenhagen surrendered quickly, and the highly populated areas of southern Norway soon followed. The first opposed paratroop attack in history took place on the first day of the invasion when the Fallschirmjäger took the Norwegian airbase of Sola near Stavanger in a surprise assault. It was a big achievement because the airfield could protect German convoys to and from Norway, but much more important objectives loomed. The first big test for the Fallschirmjäger was at the

Battle of Dombås.

|

| A Fallschirmjäger fell with no control over the descent, dangling like a doll. |

Norway is a massive country that could not be occupied in its entirety over a short period of time. The Wehrmacht secured the southern area quickly, but the British quickly set up outposts in the north at Tromso and Narvik. A few main lines of communication from south to north remained open to permit the Norwegian royal family and, to Hitler's mind, the more important royal gold reserves to escape to the British lines. That is, the Norwegians and their gold could escape if they weren't blocked along the way - but there weren't any ports or airports for the Germans to use. The entire escape route was inland along the north/south valleys (

e.g., the Gudbrandsdalen) that characterize the Norwegian interior, and the Wehrmacht wasn't there yet. A glance at the map revealed a few inviting choke-points to block the Norwegians' flight, and the best was at a crossroads town called Dombås. The presence of an escape chokepoint provides an opportunity, but only if you have the means to get there ahead of the enemy. The Norwegians had a head start and could use the railway lines that ran through Dombås. It would take at most a week for them to load the gold on a train and zip north - the royals already had evacuated to a mountain town north of Oslo. The only chance of success for the Germans was to somehow leapfrog over the retreating Norwegian lines. This was a job for the Fallschirmjäger.

|

| Fallschirmjäger dropping near Dombås, 14 April 1940. |

Kurt Student chose his most well-trained troops, the 1st Company of the 1st Battalion of the 1st Regiment of the 7th Flieger Division, for the mission. He held them in reserve until 13 April, Under the command of Oberleutnant Herbert Schmidt, it was composed of 185 men armed with standard light weapons and 22 MG 34 machine guns. The troops flew to Fornebu Airport at Oslo on 13 April and then took off for the drop near Dombås at 17:00 the next day.

|

| One of the Junkers Ju 52s shot down during the drop at Dombås. |

The weather was lousy, and the mission almost aborted. At the last minute, the decision was made to go ahead. The weather was just good enough for the drop, but the Fallschirmjäger were spread out. The planes flew low, and anti-aircraft gunners shot down ten out of the fifteen transport planes. This was a preview of things to come for the Fallschirmjäger.

|

| The main objective at Dombås, a railway station. |

Schmidt gathered his troops together - out of the 185, he had 63 with him by nightfall. They faced fierce attacks quickly from the nearby 2nd Battalion of the Norwegian Army's Infantry Regiment II (II/R 11). They were several miles from Dombås, so they blocked the road and hijacked a Norwegian taxicab. Driving ahead of his walking troops, Schmidt scouted ahead toward Dombås. He ran head-on into trucks carrying Norwegian soldiers from Dombås. A sharp firefight erupted. Schmidt was wounded, but he and his few men managed to escape.

The Fallschirmjäger spent the night at a farm just to the south of Dombås after the main body caught up with Schmidt. The Norwegians had no idea where Schmidt and his men were, so they attacked without much preparation. Against all odds, the Fallschirmjäger beat them off.

The Norwegians had the outnumbered Fallschirmjäger cornered, but just when it seemed that the end was near, a snowstorm muddled everything. The Fallschirmjäger counterattacked and threw the Norwegians back toward Dombås. Early the next morning, the Fallschirmjäger continued along the road to Dombås. They repelled more attacks by the Norwegians and finally took refuge at a farm. Schmidt's men were able to cut the railway, but only if they made it to the railway station could they hope to do any damage with strategic value.

At that point, the Norwegians closed in and brought up artillery. Schmidt held out for a couple of days, but finally surrendered. He managed to slightly delay, but not stop, the passage of the royal family and the gold along the nearby tracks. Repatriated not long after when the advancing ground forces freed him, Schmidt recovered and later published a book of his experiences which greatly helped the image of the Fallschirmjäger within the Wehrmacht.

|

| Oberleutnant Herbert Schmidt upon receiving the Knight's Cross to the Iron Cross for his actions at Dombås (Bundesarchiv Bild 183-L04881). |

Holland

The coming operations in Holland and Belgium presented some unique issues that Fallschirmjäger could help solve, so Hitler called Student in. Hitler gave Student a list of nine objectives he thought that Fallschirmjäger could help achieve, and asked him to choose two. Kurt Student decided to focus on seizing bridges over the Meuse and fortresses near Ghent. However, due to a security breach, the objective changed to the Belgian fortress of Eben Emael, north of Liege. This dominated a key route to the Belgian heartland and was considered invulnerable.

|

| The parachute drop during the invasion of Holland and Belgium. |

Hitler himself apparently came up with the idea of a glider-borne attack on the fortress. Student and Trettner formed a Sturmgruppe of 11 officers and 427 men. The main body of paratroopers would seize nearby bridges over the Albert Canal, while only two officers and 83 men would be taken to the fortress and landed on top of it by DFS 230 gliders. Oberleutnant Witzig was in command of the troops set to land on the fortress itself, with overall command of the Sturmgruppe by Hauptmann Koch.

|

| Fallschirmjager at Fort Eben Emael. |

The operation took place on 10 May, the opening day of the invasion. Witzig's glider landed in a field, so a Ju 52 landed and took him up again, this time landing him on the fortress itself. Aided by Stuka attacks, the Fallschirmjager captured the fort on the 11th, and they soon were relieved by advancing ground troops. Many consider the Eben Emael capture one of the most brilliant attacks of the entire war.

|

| A Fallschirmjäger from 7./FJR 1 firing a captured Vickers machine gun at the Moerdijk bridgehead. |

Other Fallschirmjager of the 22nd Division, including Student himself and Trettner, flew into "Fortress Holland" near Rotterdam and Amsterdam. This force, however, had a much harder time. For one thing, it was much further behind enemy lines, and thus could not be relieved quickly. The Fallschirmjager captured important bridges but were hard-pressed. A sniper badly wounded Student in the head on 14 May, but shortly afterward the defenders of Rotterdam gave up. It was a very close call and showed the sorts of limitations to airborne attacks first demonstrated at Dombås.

|

| Adolf Hitler with fallschirmjäger, all showing their new Iron Crosses with which the Chancellor has just decorated them for their success at Eben Emael, Belgium May 1940 (colorized). |

Crete

Kurt Student was laid up until September, and in fact according to some never really made a full recovery mentally. Fortunately, his sidekick Trettner was quite capable. Goering wanted to raise four more airborne divisions quickly and try to invade England with them, but cooler heads in the Wehrmacht prevailed.

|

| Former world champion boxer Max Schmeling trained as a Fallschirmjäger and made the jump on Crete. He was ill with dysentery, but his commanders ordered him to make the jump anyway. He got down, survived, and was almost immediately evacuated to Athens, where he spent the next month in a hospital. Schmelling never jumped again - but he did box again after the war. |

If Rotterdam was too far behind enemy lines for effective supply and relief of airborne troops, England would have been far worse. However, with one epic success and two failures that had been part of larger successful operations behind them, the Fallschirmjager concept now was recognized as a legitimate part of the Wehrmacht. All they needed was another target appropriate for their unique talents.

|

| A Fallschirmjäger - possibly also Schmeling - boards a Junkers Ju 52. He grips his static line in his teeth so that his hands are free to pull himself into the plane. Operation Mercury, 20 May 1941. |

The opportunity came about in May 1941. The Wehrmacht had chased the British out of mainland Greece, but they remained on the large and heavily fortified island of Crete. Crete was an important objective because it had several large British naval and air bases that could control that portion of the Mediterranean. Hitler decided to take it and authorized Operation Mercury, the invasion of Crete with airborne and air units to be relieved by seaborne troops.

|

| The armband awarded to enlisted men for service during Operation Mercury. |

It was an extremely ambitious operation, and the British troops would greatly outnumber the Germans at all times. The Germans decided to split up their forces and attack several British bases at once, in hopes that one would "get lucky" and secure an airfield through which the Luftwaffe could pour reinforcements.

|

| A Junkers Ju 52 coming in low over Crete, 20 May 1941. |

Junkers Ju 52s began dropping Fallschirmjager on Crete at 08:00 on 20 May 1941. The troops landed near Maleme airfield and the town of Chania. Opposing them were New Zealand troops bloodied on the mainland. The British had the advantage of spy intelligence such as Ultra decrypts. These enabled the defending troops to set up in ideal positions and await the descending Fallschirmjager, killing hundreds. Gliders were hit by mortars as soon as they landed, while Greek and New Zealand ground troops were nearby to finish them off on the treeless plains. To top it off, the British had tanks and artillery. It was a bloodbath.

|

| Parachutists dropping on Crete, May 1941. |

Another tranche of Fallschirmjager landed in the late afternoon near Rethymno and Heraklion. These troops made some progress, capturing some barracks, but by nightfall, the Germans hadn't accomplished much. However, New Zealand General Freyberg was worried about more landings, so he withdrew his armor from a key hill overlooking Maleme. The Fallschirmjager quickly rushed in, and General Student decided to bet all of his chips on capturing Maleme. The New Zealanders counter-attacked in the afternoon, but the Fallschirmjager seized the airfield and held it. Kurt Student fed in transports which crashed on the airfield, but some of the troops got through to reinforce the men holding the airfield.

|

| On the ground at Crete. |

The original plan was for seaborne troops to relieve the Fallschirmjager, who had achieved their objective of seizing an airfield. During the night of the 21st, the Germans on the mainland sent over 20 caïque's, escorted by the Italian torpedo boat Lupo. However, Royal Navy Force D out of Alexandria, commanded by Rear Admiral Irvine Glennie, intercepted the slow-moving boats and sank over half of the transports. Only swift help from an Italian naval squadron saved what men did not drown in their fatigues. One caique and one cutter made it to Crete. They were, however, behind Allied lines and were of no use to the hard-pressed Fallschirmjager at Maleme. The paratroopers were on their own.

|

| Fallschirmjäger arriving on Crete in a Lastensegler DFS 230 (Ang, Federal Archives, Bundesarchiv Bild 141-0816). |

Freyberg organized a counter-attack in the early hours of the 22nd. It was do-or-die for the Fallschirmjager. However, the New Zealanders suffered from poor communication and being overstretched, trying to guard the entire coast from seaborne landings. The counter-attack came in late, during daylight, and failed. Aided by Junkers Ju 87 Stukas, the Fallschirmjager held out through the day. After dark, the Germans tried another seaborne landing. A strong Royal Navy response forced the cancellation of this landing.

|

| A Junker 52 at Crete-Maleme, 21 June 1941 (Ang, Federal Archives). |

The Luftwaffe now came to the relief of the beleaguered Fallschirmjager. The planes focused, not on the New Zealand ground troops, but instead on the Royal Navy ships standing in the way of reinforcement of the troops holding Maleme airfield. They damaged battleship HMS Warspite, sank cruisers HMS Fiji and Gloucester, and sank and damaged other ships. The Royal Navy ships ran low on anti-aircraft ammunition and had to withdraw. This opened the way to the reinforcement of the Fallschirmjager, and from then on the New Zealanders were in constant retreat and eventually evacuated the island altogether.

|

| General Kurt Student at Chania/Crete, May 1941, with 1st Lieutenant Gerhard "Eule" ("Owl") Schacht. |

The airdrop on Crete was a success, and a critical one - critical because, had it failed, it would have been a huge propaganda victory for the Allies. However, German casualty estimates were extremely high, with the British immediately claiming to have killed 15,000-25,000 Wehrmacht troops. Modern scholarship suggests that the numbers were far fewer, more in the 5,000-10,000 range, but they were still quite high for a relatively minor objective. Hitler, for whatever reason (he would have had quite accurate numbers of German casualties), gave up on further independent Fallschirmjager operations, famously stating:

Crete has shown that the day of the paratroops is over.

In the long run for the Wehrmacht, this probably was the right move. Tactics simply were not sufficiently worked out to use Fallschirmjager with high confidence of success.

|

| Fallschirm-Jäger armbands and badges. The left badge is the Fallschirmschützenabzeichen der Luftwaffe (Fallschirmjäger Badge), while the right one is the standard Erdkampfabzeichen der Luftwaffe (Luftwaffe Ground assault badge). |

The specter of massive failure floated over any operation such as Crete. However, Hitler was wrong, and properly handled, Fallschirmjager and Allied paratroops could be quite useful. Because of Hitler's decision, several extremely important objectives - such as Malta - were abandoned or made impossible by this decision.

|

| A memorial put up by the Germans on the outskirts of Candea (Chandia) during their occupation of the island to commemorate the role of the Fallschirmjäger force in Operation Mercury. It stood intact until the 21st Century - in 2001, the Eagle fell off. The slab still remains. |

North Africa

After Crete, Fallschirmjager would fight in every theater, but as an adjunct to ground troops. Never again would Fallschirmjager mount an independent operation to achieve an objective unattainable by land forces.

|

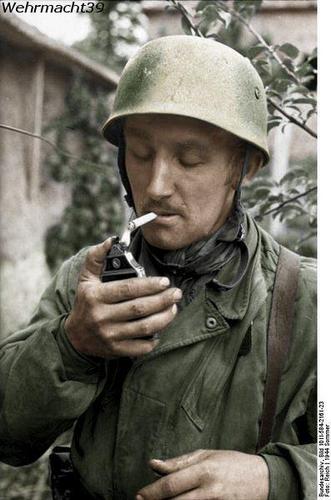

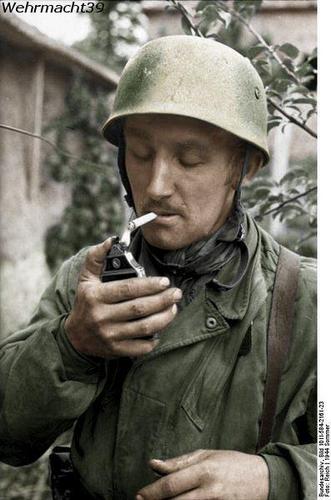

| A Fallschirmjager apparently in North Africa, 1942-1943. |

In North Africa, Major General Bernhard Ramcke’s Fallschirm Brigade arrived in July 1942 to reinforce the Afrika Korps on the El Alamein front. The force gave a good accounting of itself, but Ramcke's four battalions could do little to halt the British counteroffensive. However, for what it is worth, they played a key role in holding the El Alamein long far longer than it had any right to survive. The 5th Parachute Regiment under Oberstleutnant Koch helped to defend Tunis, but by then the Axis position in North Africa was hopeless, leading to total defeat there in May 1943. A later operation involving Fallschirmjager to recover the Greek island of Kos in late 1943 was successful but essentially pointless.

Italy

After the disaster at Tunis - or "Tunisgrad" as the Germans came to call it - the Germans mounted a very successful defense of Italy. While almost always retreating, a series of successful delaying actions made the theater a source of pride within the Wehrmacht.

|

| A Fallschirmjäger Unteroffizier in Italy, September 1943 (colorized by Doug). |

The 7th Fliegerdivision, now renamed as the 1. Fallschirm-Jäger-Division (1st Parachute Division), participated in the defense of Sicily. At one point, Fallschirmjager parachuted in and landed at a key spot only minutes before a major Allied attack, managing to hold the line when otherwise it would have been breached. That said, Sicily was conquered quickly, and there was little Fallschirmjager could do about it.

|

| Fallschirmjager, Italy. |

The 1. Fallschirm-Jäger-Division was put in the line and fought well at the Battle of Ortona against the 1st Canadian Division. This progressed into the Winter Line battles south of Rome, with the German defense anchored at Monte Cassino. The 1. Fallschirm-Jäger-Division did outstanding work at Monte Cassino, holding the position for months. It was one of the shining moments of the entire Wehrmacht in the closing two years of the war. Finally, faced with Allied flanking maneuvers, the Fallschirmjager joined the general retreat past Rome to the Gothic line in northern Italy.

|

| A soldier of the 4 Fallschirmjäger Division (Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe, sygn, 2-2164, colorized by Doug). |

The 4th Fallschirmjäger Division was formed at Venice in November 1943 through the usual expedient of splitting off part of another division, in this case, the 2nd Fallschirmjäger Division. To this was added some "volunteers" of the Italian 184 and 185th Airborne Divisions. They were brought down to Anzio and helped to hem in the luckless Americans who had landed at Anzio as part of Operation Shingle. After that, they retreated north toward Florence (Firenze) until they managed to dig in at the Futa Pass along the Gothic Line. Parts of this division were then taken to help form the 10th Fallschirmjäger Division being formed in Austria. The 1st and 4th Fallschirmjäger Divisions joined together to form the German I Parachute Corps, helping to hold the German line together into the closing months of the war.

Anti-Partisan Operations

|

| Operation Rösselsprung, 25 May 1944. |

One of the unexpected uses of the Fallschirmjäger units was in anti-partisan activities. While partisans operated throughout Occupied Europe, there were certain hot-spots that drew special attention. In no particular order, these were:

Now, singling these places may make the people of other nations such as Norway and Holland feel slighted. However, in those three regions, the Wehrmacht engaged in massive military operations that dwarfed anti-partisan activities elsewhere. They had the ideal support for partisans: fierce national identity, rough/wooded landscapes and vast areas of loose German control.

Anti-partisan operations were not haphazard affairs. They typically included multiple regular Wehrmacht units and a well-planned assault from multiple directions on a particular area. There were several anti-partisan operations in the Army Group Center rear area in Russia, for instance, that involved real battles for control over vast stretches of territory (a Rayon/raion or oblast). Elsewhere, the anti-partisan operations generally were just as carefully planned but involved nebulous targets with no fixed defenses and partisans who could simply walk out of the area while blending in with everyone else. As an example, the Germans were determined to eliminate Tito and his partisans in Yugoslavia. Now, Yugoslavia was a special situation because there were competing communist and royalist partisans that did not particularly get along, but at various times they controlled vast sections of the region. They were a continuing problem for the Germans that drew full-scale military assaults.

Operation Rösselsprung began with a pre-assault bombardment and then an advance by ground troops of XV Mountain Corps. Then, at 07:00, 314 men of the SS-Fallschirmjäger-Bataillon 500 jumped out Junkers Ju 52s at Drvar in the Independent State of Croatia, while 320 men landed nearby in gliders. The second wave of 220 men dropped later, accompanied by two gliders bringing in supplies at 12:00. Junkers Ju 87 Stukas attacked targets within Drvar and Bosanski Petrovac.

|

| The main objective of Operation Rösselsprung was Tito's mountain retreat, shown here in 1990 (Wikipedia). |

Despite the usual problems - some gliders landed in the wrong place, the ground forces killed many men in the air and so forth - the Germans came within a whisker of capturing/killing Tito himself. Holed up in a cave, he had to climb through a trapdoor and descend on a rope to a creek that he and his associates (including his mistress and her little dog) followed to safety. In general terms, the Germans considered the operation a success, claiming 6000+ partisans killed at a cost of 213 killed, 51 missing and 881 wounded from their own forces. The partisans, of course, saw things differently, claiming roughly the same number of casualties as the Germans. Similar operations elsewhere in very general terms produced similar results.

While historians don't look at these types of operations as being particularly successful in eradicating the partisan threat, it is like weeding the garden: you may not get all the weeds, but at least you keep them from taking over the entire yard.

Russia

General Student proposed several major operations by his Fallschirmjäger in Russia. For example, he wanted to use his troops to capture the Crimea, and also to occupy the Kola Peninsula near Pechenga, Norway. However, the overall state of the Wehrmacht made any such operations too risky.

|

| 2nd Fallschirmjäger Division troops on a Tiger tank near Berdychiv during the successful Zhytomyr operation in November/December 1943. They are hitching a ride with the 8th Company of the 2nd SS Panzer Regiment of the 2nd SS Panzer Division "Das Reich." This is Battlegroup (Kampfgruppe) Lammerding. |

The 7. Fliegerdivision deployed near Leningrad in late 1941, fighting as ground troops. They fought hard and took over 3000 casualties. The Fallschirmjäger fought against a Soviet beachhead east of the city at Petruschino. Some units also deployed near Moscow. However, the OKW withdrew all 7. Fliegerdivision troops from the Russian Front in January 1942 and sent them to France for rest, refit and training.

|

| A Fallschirmjäger with a Fallschirmjager Gewehr (FG) 42 with ZF4 optic sights. |

The 7. Fliegerdivision returned to the Eastern Front in October 1942. While the center of Wehrmacht operations at that time was at Stalingrad, the division went to the Smolensk sector. Fighting near Rzhev had been tough all summer long, and the Fallschirmjäger helped to defeat Marshal Zhukov's Operation Mars offensive in November - one of the virtually unknown Wehrmacht successes of the war (it was supposed to be a companion piece to Operation Saturn at Stalingrad, but utterly failed).

|

| This shot shows how the parachute opens. The plane also is dropping unit equipment. |

The 2. Fliegerdivision took up positions near Zhytomyr in the Kyiv sector late in 1943. After the fall of Kyiv in early November 1943, a successful counteroffensive briefly retook Zhytomyr and some other important junctions under General Manteuffel. The Fallschirmjäger played a key role at the Battle of Leros. After this, they were airlifted to Kirovograd and put in the front near Novgorodka. This was bitter ground fighting, but the Fallschirmjäger again acquitted themselves well.

|

| Getting ready to jump. |

In early 1944, the Red Army launched a major offensive against the 2. Fliegerdivision. This caused a general retreat, with some units of the division destroyed (2nd Battalion of the 5th Regiment, for instance). The Soviets forced the Germans back against the Bug River, and then the Dniester. Worn out, the division returned to Germany.

Normandy

The Fallschirmjäger troops were ready for the Allies. The 6th Fallschirmjäger Regiment of the 2nd Parachute Corps was near Carentan in the Cotentin Peninsula. They dug in around Saint-Lô and helped to stabilize the line after the initial Allied surge, then moved down to Brest around 13 June. On 11 July, the 9th Parachute Regiment launched a counterattack against the US 115th Infantry Regiment that caused the opposing Americans some problems. On the same day, the 3. Fliegerdivision took severe casualties, mainly from artillery, at St. Lo.

|

| A Fallschirmjäger during the summer of 1944 (Federal Archive). |

Brest was not a particularly good place for the 2. Fliegerdivision to be. The paratroopers were caught south of the Allied breakout at Avranches and tried to get out, but were on the wrong side of the breakout and retreated to Brest. The remnants of the division were withdrawn to Cologne.

|

| Fallschirmjäger in Normandy. |

By this point, the Fallschirmjäger units were scattered and could no longer be considered an independent force. Units in Italy, France, and Poland did what they could to stem the Allied advance. The 9th Parachute Division was destroyed on the River Oder, and then in Berlin itself.

|

| 2 Fallschirmjäger Division men and officers after surrendering at Brest, 19 or 20 September 1944 (colorized by Richard James Molloy). |

By the middle of 1944, there were 160,000 Fallschirmjäger despite Hitler's edict that their "days were over." Goering, ever eager to expand his personal Luftwaffe fiefdom, had dreams of forming them into an independent Fallschirmjäger Army. Kurt Student stayed in Berlin working on this hopeless project without a real purpose.

However, he eventually gained command of Wehrmacht forces in Holland - just in time for British Operation Market-Garden in mid-September 1944. He personally watched Allied airborne troops land near his headquarters house on 17 September. He captured some enemy plans and, understanding the limitations of parachute troops, organized the defense that stopped the Allies cold at Arnhem.

|

| Towards the end, with everything in chaos, men shifted about without regard to "specializations." Here, a Wehrmacht jack-of-all-trades is surrendering surrenders on 10 May 1945 near Soest, Holland. He's wearing paratrooper (M38) pants, but he also has a bomber (Kampfflieger) clasp and a Ground Assault Badge. None of these may have been his, or all of them - who can say, perhaps he scavenged everything. However, Luftwaffe bombers rarely flew in 1945, so he probably was converted to infantry His highest award - he managed to survive at all (photographer Willem van de Poll, colorized by Rui Manuel Candeias). |

Kurt Student wound up commanding Army Group H but was quickly replaced. The days of the Fallschirmjäger now indeed were over - but only with Germany's final defeat.

2020

No comments:

Post a Comment