Horses Were Vital to the German War Effort in World War II

|

| Horses were extremely important within the Wehrmacht. |

There seems to be a misconception in some quarters that World War II was the first purely mechanized war, and that horses were entirely superfluous to the course of events.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Horses, in fact, were incredibly important to the course of World War II, from the first day almost to the last. Many have heard the tales about Polish cavalry charging against advancing panzers during the Battle of Poland in 1939, but the story of horses during World War II goes much deeper than that. Let's look at a few key uses of

horses during World War II.

1939: Polish Charge of Krojanty

We've all heard the legends about how the Polish cavalry made futile charges against the panzers and got slaughtered. This has become a point of pride for the Polish, who deeply resent the idea that they were completely powerless against the advancing Wehrmacht.

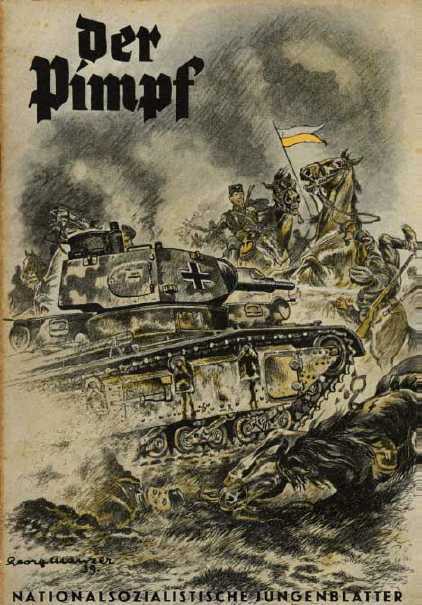

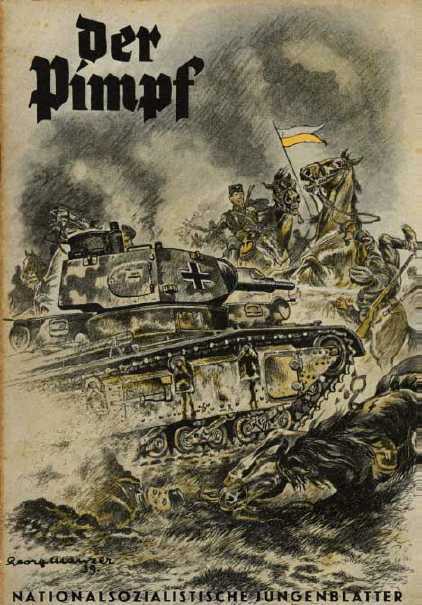

|

| "Der Pimpf" - this is a Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend) publication portraying the panzers sweeping across the hapless Poles and their cavalry. |

Well, embarrassing as it may be for the Poles, it did happen. There's plenty of embarrassment to go around during the war years, so it's nothing to be ashamed of. In fact, the futile advance of the Polish cavalry is nothing to be ashamed about at all. In fact, it is kind of glorious in a romantic, lost-cause sort of way.

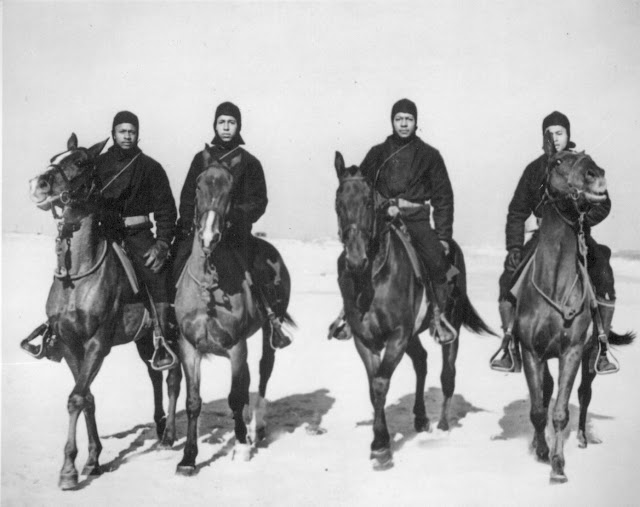

|

| Polish cavalry in September 1939. Exactly where and when is unclear. Some sources say this was taken during fighting in Sochaczew. |

The incident known as the charge at Krojanty happened right at the outset of World War II, on 1 September 1939. The village of Krojanty is located near Lake Charzykowskie and the Tuchola forest. The charge at Krojanty is part of the larger Battle of Tuchola Forest. There is all sorts of myth and legend, truth and falsehood, about this incident. Let's just get the facts out quickly, without a lot of weaving around.

|

| Summer 1941 (Buschel, Federal Archive). |

The German 76th Infantry Regiment (Colonel Hans Gollnick) of 20th Motorised Division (Lt. Gen. Mauritz von Wiktorin), all part of the left (northern) flank of XIX Panzer Corps (Gen. Heinz Guderian), was advancing across the Danzig (Gdansk) Corridor in Pomerania. This was a stretch of Poland that the Germans deeply felt they deserved, having been taken from them pursuant to the treaties ending World War I. The Wehrmacht had men in Danzig in plainclothes just waiting for the invasion, and those men already had sprung into action. They needed to be relieved, or it would be a major embarrassment for the Third Reich. Thus, General Guderian had multiple reasons to get to Danzig, and fast.

|

| Wehrmacht soldiers leading their horses across the Vistula/Weichsel River bridge (Federal Archives). |

The Poles had a defensive line of sorts at the river Brda (Brahe). The advancing Germans reached a railway line near the Tuchola Forest heath (grasslands) and took Chojnice (Konitz). During the late afternoon, the Germans apparently stopped to eat just beyond there - imagine the tension they had been under all night long, with the invasion looming, and then fighting against the Polish border forces - and the Poles saw an opportunity to attack.

|

| A typical Schwerer Panzerspähwagen (6 Rad Sd.Kfz. 231). |

At about 17:00, the Poles charged. Eugeniusz Świeściak led about 250 men of his 1st Squadron of the 18th Pomeranian Uhlans against the resting German infantry. The Poles sent the bemused Germans running for the nearby woods. What the Poles didn't count on, however, was nearby German armor. The Wehrmacht vehicles swept across the heath and sent the Poles reeling under heavy .20 mm machine gun fire from Schwerer Panzerspähwagen (armored cars). Świeściak perished, as did his commander, Colonel Kazimierz Mastalerz, who had ordered Świeściak and his men to make the charge. The Poles suffered huge casualties.

As is always the case in such situations, some make the argument that the attack "bought some time for other Polish units to withdraw." Well, the Germans weren't advancing at the time and probably would have bivouacked in the vicinity for the night anyway, so that is perhaps a bit of rationalization. General Guderian, who led from the front, soon heard about the incident and told his men to forget about the Polish cavalry and get moving again toward Danzig. Axis war correspondents quickly seized on the incident, which did feature a lot of dead horses and Polish soldiers to support the notion that the Poles rode horses against tanks. The cavalry did wind up engaging German armor, so that part is true, but not (apparently) intentionally.

|

| Polish helmets piled up after the charge at Krojanty. |

There were other incidents during the Polish campaign of a somewhat similar nature, but the charge at Krojanty is the one that began the tales of Polish cavalry jousting with panzers.

Operation Barbarossa

My main source for this section is "Moscow to Stalingrad: Decision in the East," Earl F. Ziemke and Magna Bauer (Military Heritage Press 1985).

|

| Feeding the horses was a daily ritual. Unfortunately for the horses, their food supply became almost exclusively hay as the Operation Barbarossa campaign progressed, and not enough of that, either. |

The Germans opened Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, with 600,000 motor vehicles and 625,000 horses. That the number of horses was larger than the number of vehicles was no surprise, because the Wehrmacht had been rearming for less than a decade and had not had time to assemble a larger fleet of purpose-built vehicles. In fact, transportation issues were one of the Wehrmacht's biggest issues throughout the conflict. Horses were particularly valuable because they don't need oil and gasoline, both in perpetually short supply within Germany (and one of the main reasons why they began the war in the first place, though there are various theories on that). Horses were critical for troop movements and supply (carrying goods from supply trains to the field).

|

| A German soldier with a horse and Heer (army) wagon. |

The campaign took a huge toll on horses. A 19 March 1942 OKW (German military high command) report found that 179,000 horses had perished by that point, with only 20,000 replacements. That brought the total number of horses well below half a million. The situation became so acute that the military had to requisition 250,000 horses from Occupied Europe. The situation was made worse because civilian motor vehicles built for paved roads and plentiful servicing were breaking down not just from use in Russia and the intense climate there, but from the trip to get there (only about a quarter of those sent east actually made it to where they were needed). In addition, horses bred for other purposes were not as powerful as those bred for military work.

|

| A German officer on 21 June 1942. The location is unknown, but a favored military expression was that you would fight until you see your horse drink from the enemy's home river (Federal Archive). |

The main source of German supply throughout the conflict was by railroad. Horse-drawn vehicles were essential for delivering daily supplies to troops in the field. During the Soviet counteroffensive at Moscow, Hitler's use of stand-fast orders compelled men to sit in isolated positions without food supplies - except for their horses, which themselves were not being fed well. As the number of horses dwindled, the Wehrmacht was forced to fall back on its railheads. This made the railroads obvious targets for partisans. In fact, Soviet-led partisans also used horses for guerilla operations.

|

| German cavalry soldiers showing how to use their mounts as gun platforms. |

There were only two active cavalry units in the Wehrmacht (aside from mountain troops which had units equipped with horses). One was the SS Cavalry Brigade (8th SS Cavalry Division Florian Geyer). Its commander during Operation Barbarossa is well known to history, but for vastly different reasons than his command of a cavalry unit. He was Brigadefuehrer (Brigadier General) Otto Hermann Fegelein. Yes, the same Fegelein from the bunker in 1945. Fegelein was dating Hitler's mistress' (Eva Braun's) sister (they married in June 1944, just days before D-Day). The SS Cavalry Brigade, however, was just a showpiece - it was never intended for combat. But, it turns out, it was capable of fighting, or at least skirmishing.

|

| Men of the SS Cavalry Brigade (Federal Archive, Bundesarchiv Bild 101III-Adendorff-002-18A). |

Fegelein loved horses but wasn't much of a commander. However, he had to lead his troops in an attack to save Rhez, a vital German strongpoint at the end of a railway, in January 1945. Fegelein obligingly led his men into the whirlwind and fought the Soviets so hard that his men ran out of ammunition and had to pull back. Their mission was a success: Germans held Rzhev, though that likely was due more to a sudden blizzard than anything the cavalry did

|

| The original caption of this photo was "Übermantel und Pferd" (winter coat and horse). Apparently, the soldier is in the German mountain troops ("Gebirgsjäger"). |

The SS Cavalry Brigade remained on the Eastern Front throughout the war, as experience showed that it could come in handy in a crisis. It helped with anti-partisan activities, reconnaissance, helping with retreats (such as Operation Buffalo in early 1943 and the retreat to the Dnepr (Dneiper) River). It ultimately was engulfed with the Wehrmacht units trapped in Budapest in 1945.

1945: Battle of Schoenfeld

The Battle of Schoenfeld is not exactly a famous battle. Nobody ever is going to confuse it with the Battle of Stalingrad or anything like that. However, it does have one claim to fame: it featured the last horse cavalry charge in modern warfare.

|

| Polish cavalry ca. 1945. |

By 1945, of course, the German Wehrmacht was in full retreat on all fronts. The Soviets were blasting into Pomerania, and the Germans were trying to hold the coast. Why the Germans were trying to hold the coast is a long story, but basically the Kriegsmarine,

i.e., Admiral Doenitz, had told Hitler that Germany needed to retain the coast - the

whole coast - in order to continue its operations. In addition, due to Hitler's stand-fast/fortress strategy, there remained a large concentration of German forces in Stettin (never mind Courland) who would be cut off by a Soviet advance to the coast. So, the Germans were in the odd situation of trying to prevent the Soviet force from advancing from south to north when Berlin and the heart of German were to the southwest. It didn't make sense to a lot of Wehrmacht commanders at the time, but that's where we enter the story.

|

| The Polish 1st Cavalry Brigade around the time of the Battle of Schoenfeld in March 1945. |

The Soviets made liberal use of Polish troops at this stage of the war. The First Army of the Polish People's Army was advancing on the village of Schoenfeld/Borujsko/Żeńsko (everything in this part of the world has at least three names) and the Germans were tasked to stop them. Stettin is only about 50 miles (80 km) northwest of Schoenfeld, and every mile counted. The Germans had built, or at least conceptualized, three separate lines of fortifications in the area. Schoenfeld was on the last line.

|

| Hungarian soldiers near the village of Ivanovka Khokholsky in the Voronezh region, 1942 (Tamas Conoco Sr.). |

The Germans in Schoenfeld did not know who was going to attack them, but they knew an attack was coming. On 1 March 1945, the 163rd Infantry Division under General Karl Rübel was dug in with anti-tank weapons on the outskirts of Schoenfeld waiting for the usual assault infantry, perhaps supported by T-34s and larger Stalin tanks. The Polish 2nd Infantry Division under General Jan Rotkiewicz obliged and made the usual armor-plus-infantry advance on the village. The Germans repulsed this uncreative assault without too much trouble. However, next, they got something that they weren't expecting: a cavalry charge by the 1st "Warsaw" Independent Cavalry Brigade under the command of Konstanty Gryżawski.

|

| Marching somewhere in Ukraine, probably retreating, at the pace of the horses, 1942 ((Tamas Conoco Sr.). |

General Gryżawski sent two squadrons of horse-mounted cavalry, supported by some horse-drawn artillery, through a ravine which the Germans rightly thought was impassable to vehicles and thus not much of a threat. However, the horses got through the ravine just fine. This enabled the Poles to achieve the element of surprise and roust the Germans from their forward antitank gun positions on the slope of a hill (Hill 157) in front of the town. Having taken this foothold, the Poles waited for the tanks and regular infantry to catch up, then charged into the town itself. By 17:00, the Germans were on the run to the north and the Poles had occupied the town. Total casualties were about 500 Germans, seven Polish mounted cavalry, 16 Polish tank soldiers, and 124 Polish infantry. The modern location is Żeńsko, Drawsko County, Poland. It was the final verified mounted cavalry charge of World War II (there may have been some by Polish cavalry during April, too, but little is known about that). It ended a glorious epoch of the horse as the queen of battle.

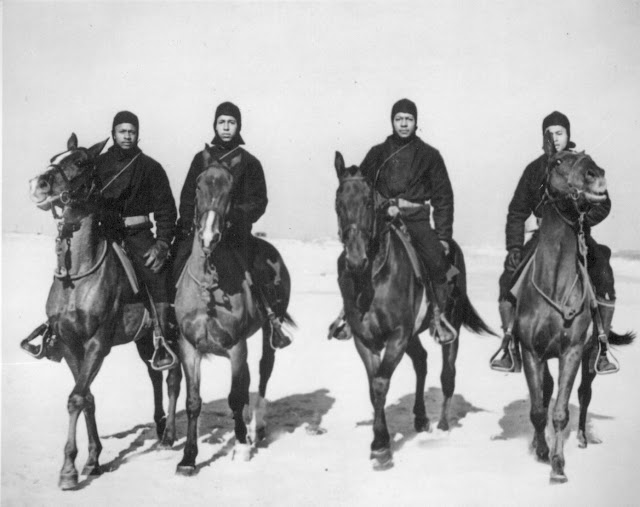

|

| The Allies used horses as well. Here are Coast Guard members patrolling a beach in New Jersey (Left to right: seamen first class C. R. Johnson, Jesse Willis, Joseph Washington, and Frank Garcia) (Archives.gov). |

Conclusion

Horses were used extensively during World War II. Not only were they effective at hauling large loads for long distances, but they also did not use up scarce commodities like oil and rubber. They were particularly useful during operations in Eastern Europe, where roads were bad and often non-existent and hay relatively plentiful. While the other combatants all used horses to one extent or another, they were a major component of the Wehrmacht, which could not have operated effectively without them.

|

| Soviet cavalry in the Caucasus. They could go where panzers could not. |

2020