Honorable Admiral or Naval Terrorist

|

| Admiral Karl Doenitz. |

The simple answer to whether German Grand Admiral (Großadmiral) and Reichs President (Reichspräsident) Karl Doenitz (Dönitz) was a war criminal is "yes." That is because he was convicted on two of three war crimes charges. Doenitz was sentenced to ten years in prison (actually over 11 years including time served). However, simply saying that Doenitz was a war criminal does not answer why.

Let's look at why Karl Doenitz was convicted at Nuremberg.

Doenitz's Background

Karl Doenitz was born in Grünau near Berlin, Germany, in 1891. He enlisted in the Kaiserliche Marine ("Imperial Navy") in 1910 and was a Leutnant zur See (acting sub-lieutenant) on the cruiser SMS Breslau when World War I began. Doenitz transferred to the submarine service as an Oberleutnant zur See (full Lieutenant) in 1916 and attended the submarine service's school at Flensburg-Mürwik, graduating on 3 January 1917. He rose to command UB-68 in the Mediterranean but was forced to scuttle his boat on 4 October 1918, becoming a prisoner of war. In 1920, he returned to Germany.

During the interwar period, Doenitz remained in the navy (which was considered an honor, as the size of the German military was greatly restricted due to the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles) and continued his rise through the ranks. When the Reichsmarine was renamed Kriegsmarine in 1935, Doenitz was in command of the training cruiser Emden. Germany was prohibited at this time from having a submarine fleet, but Hitler negotiated the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935 that erased this prohibition. Almost immediately, Doenitz was placed in command of the U-boat flotilla Weddigen.

|

| Karl Doenitz in 1935, with the grade of captain, inspecting U-7 (photo Karl Daublebsky von Eichhain). |

Doenitz, now a Kapitän zur See (naval captain), began developing U-boat group tactics. He quickly became the dominant person in the entire new U-boat service. Doenitz preferred smaller submarines, as opposed to some other powers such as France and Japan that built giant submarines, due to pragmatic issues such as cost of construction and tactics. Ultimately, he settled on the Type VII submarine, which had a range of 6200 miles that later was extended to 8700 miles. In terms of tactics, Doenitz settled on the Rudeltaktik ("wolfpack"), wherein groups of U-boats would overwhelm a convoy's defenses by working together. This was somewhat similar to similar strategies in the German Army (Heer) in which massed tank tactics were favored. Improved radio communications, directed by a central command in Berlin, made the wolfpack tactic possible.

Doenitz During World World Two

Following a

14 August 1939 meeting at the Berghof in Berchtesgaden with his ministers and military leaders, Adolf Hitler decided to wage war with Poland. On

15 August 1939, sent a coded message to Doenitz, since 28 January 1939 the Commodore (Kommodore) and Commander of Submarines (Führer der Unterseeboote). It instructed Doenitz to send the U-boat fleet to sea and to take up stations off the coast of Great Britain.

|

| British liner SS Athenia sinking on 3 September 1939. |

Doenitz's problems began quickly. On the first day of the war with Great Britain, 3 September 1939, U-30 (Oberleutnant Fritz-Julius Lemp) torpedoed and sank the 13,465-ton British liner Athenia about 200 miles northwest of Ireland. There were 98 passenger and 19 crew deaths. The sinking clearly violated international law, which required U-boats to stop the ship and allow the passengers to disembark. The Kriegsmarine commander, Grand Admiral Raeder, quickly denied responsibility for the sinking, Lemp informed Doenitz of the truth when he returned to port. Doenitz sent Lemp to Berlin to talk to Raeder, who referred the matter to Hitler. After consultations, Hitler decided to keep the matter secret. despite the fact that this was a violation of the rules of war. The German Propaganda Ministry blamed the loss on the British themselves, which began or at least accelerated a cycle of distrust between the two naval powers.

|

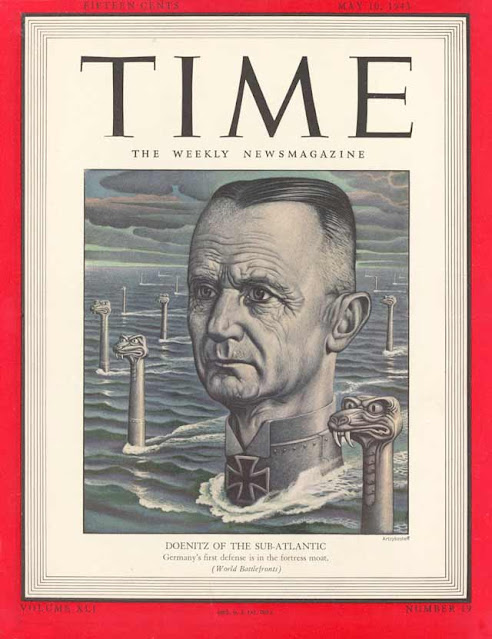

| Time Magazine of 10 May 1943 featured Admiral Doenitz on the cover. |

Adherence to the "rules of war" quickly fell by the wayside. On 23 September 1939, Hitler ordered that any freighters using a radio should be stopped and then sunk or captured. On 27 September 1939, he ordered the enforcement of Prize Regulations ended, and on 2 October 1939, all darkened ships in the war zone were made subject to immediate attack. On 17 November 1939, U-boats were authorized to attack any passenger liners (such as the Athenia) that were considered "hostile."

|

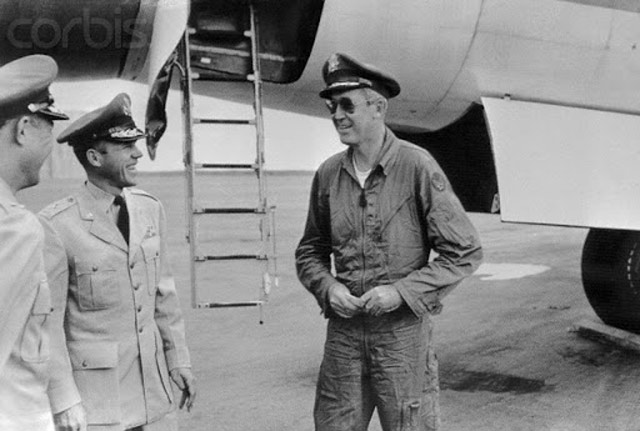

Admiral Karl Doenitz (third from left), as he replaces Erich Raeder as commander-in-chief of the German naval forces in January 1943.

|

Doenitz was not blameless in the gradual but inevitable adoption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Raeder and others later described Doenitz as a fervent Hitler follower and confirmed anti-Semite. Doenitz was in favor of unrestricted submarine warfare, along with Raeder. However, ultimately this was not his decision to make. That decision could only be made by the head of state, Hitler, because of its obvious political ramifications. Heartily embracing the new policies, Doenitz, on 1 October 1939, became a Konteradmiral (rear admiral) and "Commander of the Submarines" (Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote, BdU). This placed him in supreme command of all U-boat operations and, ultimately, of the German command of the vast majority of the Battle of the Atlantic.

Doenitz's wolfpack tactics proved successful. Men died in freezing waters or of starvation in lifeboats or trapped below decks of sinking tankers. Sometimes, entire crews perished and there were no survivors, no memories, sometimes not even any flotsam or jetsam. It was a brutal campaign and both sides used brutal tactics.

Despite occasional (and unproven) accusations of atrocities, U-boat commanders often helped the survivors of the ships they had sunk, giving them directions and food. This may have been cold comfort to the survivors, but it showed a certain camaraderie of the sea when truly vicious sailors might have acted quite differently. In the

Laconia Incident of 12 September 1942, Doenitz personally ordered nearby U-boats to attempt rescue operations of passengers from a sinking ocean liner off the African coast. Over 1000 men, women, and children were saved who otherwise might not have been. Doenitz was not as hard-hearted as some might have wished to portray him, and this would count in his favor... later. However, after the attempted rescue backfired because American aircraft attacked the Axis ships attempting the rescue, Doenitz issued

the Laconia Orders forbidding such rescues in the future. This was very controversial, and some U-boat commanders continued to render aid to people struggling in the water after their ships sank despite the orders.

|

Karl Doenitz makes a radio broadcast speech after the assassination attempt on Hitler, 21 July 1944. Watching him is Hitler and another survivor of the failed plot.

|

The U-boat campaign had its ups and downs, reaching peaks in early 1941 (the "Happy Time") and then again in 1942 during Unternehmen Pauckenschlag (Operation Drumbeat), when U-boats operated with virtual impunity off the eastern coast of the United States. Hundreds of ships were sunk as U-boats attacked any non-German ship they saw, including neutral ships. Doenitz personally controlled U-boat operations from his headquarter in Paris, making frequent trips to the major U-boat bases along the French coast to greet returning U-boats and provide inspiration to the sailors. By May 1943, however, new Allied tactics and defensive equipment had neutered the U-boat fleet. It never again posed a true threat to the Allies despite achieving regular small successes.

|

Admiral Doenitz meets with Hitler in 1945.

|

On 30 January 1943, Doenitz succeeded Raeder as Grand Admiral due to the latter's disagreements with Hitler and the failures of the German surface fleet. By 1944, Doenitz's U-boats were preoccupied with mere survival given the oppressive Allied advantage at sea. Hitler, however, never lost faith in Doenitz, perhaps because only the U-boat service continued to report victories (albeit increasingly rarely) right up until the end of the war. When Hitler committed suicide on 30 April 1945, he appointed Doenitz (to the surprise of many) as his successor. This was more a formality than anything substantive, however, as Doenitz's only substantive act was the surrender of the Reich's armed forces.

Doenitz At Trial in Nuremberg

The Allies arrested Doenitz at his seat of government in Flensburg, northern Germany, on 23 May 1945. The Allies dissolved the German government and sent Doenitz to Nuremberg to be tried for war crimes. The International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg indicted him on three counts: (1) "conspiracy to commit crimes against peace," (2) "Planning, initiating, and waging wars of aggression," and (3) "crimes against the laws of war." Doenitz was not indicted on a fourth count of "crimes against humanity."

|

Otto Kranzbühler at Nuremberg.

|

With the cream of the Kriegsmarine to choose from, Doenitz asked Otto Kranzbühler, a crafty lawyer who some considered the best counsel in the trials, to represent him. It was a wise choice. Kranzbühler was a young and flamboyant junior naval officer (he held the rank of Flottenrichter (Navy Judge in the rank of a Kapitän zur See)) who came into his own as Doenitz's counsel. He may have been in part the inspiration for the classic defense lawyer played by Maximilian Schell in "Judgment At Nuremberg" (1961). As a stunt, Kranzbühler made his initial appearance before the international tribunal in his full Kriegsmarine uniform (causing the Soviet guards to almost arrest him). This was calculated to imply that if the head of the Navy was on trial, then it would be the Navy that would defend him. It also implied that it was the German Navy itself that was on trial and that the navy did not disown its former leader. In a military court, this meant something.

|

Otto Kranzbühler makes the case.

|

Kranzbühler put on what may fairly be characterized as a brilliant defense. As suggested by his dramatic entrance, Kranzbühler took the charges against Doenitz personally. He immediately made it clear to the tribunal that, though on the losing side of the war, Dönitz was not deserving of the indictments brought against him. Kranzbühler also argued that if the Grand Admiral of the German Navy was to be tried, he should be addressed by the court with the respect he deserved as a military leader. The Allies, however, did not agree. While the prosecutors (including Chief Prosecutor Robert Jackson) and judges at Nuremberg continued to address Doenitz without any recognition, Kranzbühler always referred to his client as Grand Admiral, or "Herr Grossadmiral."

|

| US Admiral Chester Nimitz helped out a fellow admiral from the other side when it mattered most (US Navy). |

The first charge was that sinking Allied freighters was illegal. To defend Dönitz, Kranzbühler shrewdly obtained from US Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of the United States Pacific Fleet, an interrogatory in which he extracted various items of information about American naval practice. Nimitz answered sensitive questions about the practice of the United States Navy concerning submarines and merchant ships. These included US naval practice when a submarine crew had no way of knowing whether or not a ship was armed. Nimitz's answers made it clear that the German practice of attacking merchant ships was indistinguishable from the United States' unrestricted submarine warfare in the Pacific. Kranzbühler skillfully used the interrogatory to show that what his client had done, which was similar to the actions of the Allies was in accordance with the practice of war at sea at the time, and therefore was not criminal.

The prosecution unwisely attempted to use the Laconia Orders that forbade rescues of passengers and crew against Doenitz. This backfired badly on the Allies because it enabled Kranzbühler, who was no fool, to bring up Doenitz's attempt first to try to save the passengers. The fact that the attacks on the U-boats were by US aircraft was doubly effective because it reinforced Admiral Nimitz's admission to the brutality of the US military. In a naval war that saw savagery and mistakes by both sides, guilt and innocence became shades of gray.

Kranzbühler's audacious gambits worked. The Tribunal found Doenitz not guilty for his conduct of submarine warfare against British armed merchant ships. However, this was a limited victory, as the Tribunal did hold that the sinking of neutral ships was a violation of existing law.

Acquitted of the most serious charge against him, Doenitz was sentenced by the Tribunal to 10 years in prison for his conviction related to waging a war of aggression. Doenitz's carrying out of the order to conduct unrestricted submarine warfare was not officially included in his sentence, but it almost certainly influenced the verdict. It was the main reason why most judges wanted him convicted. Doenitz served 10 years in Spandau Prison plus the additional 18 months he had spent at the Mondorf and Nuremberg prison camps while awaiting trial and being tried. However, but for the efforts of Kranzbühler, particularly in respect to his defense to Count #3 above, Dönitz likely would have served a much longer sentence or perhaps even have been sentenced to death (the British and Soviet judges wanted to execute Doenitz and were only restrained by the US and French judges). It was one of the most amazing legal coups of the post-war trials.

Conclusion

Doenitz was not a "good man" as we would understand the term. He did not share our values. Among other faults, Karl Doenitz hated Jews, he helped to initiate and waged a ruthless war of annihilation that killed defenseless people on ships, he strove to imbue the submarine service with an air of Hitlerism, and he gladly accepted the leadership of one of the most brutal regimes of all time. However, this article is not about whether we would have anything common with Doenitz, a convicted war criminal. He was justly convicted for his crimes and served his time. His trial and defense by lawyer Kranzbühler before the Military Tribunal served the useful purpose of discharging some of the tensions between the victors and the vanquished of World War, and that at least made up for some of the violence Karl Doenitz committed on behalf of the Third Reich.

2020