|

| Joseph Goebbels photobombs Hitler. |

There is an art to shooting good propaganda shots. The whole objective is to create the appearance of reality. Of course, what is being shot usually is reality, and not completely constructed - but that's not enough. You need the appearance of reality, too.

Below is an example, SS soldiers look straight ahead, at attention, the camera capturing a simple parade formation. This is a textbook shot, capturing a moment.

|

| 15th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Latvian) at attention. |

And below, another typical photo.

|

| The British Free Corps, or Legion of St. George, at attention. The British Free Corps was a unit of the Wehrmacht and consisted of British and Commonwealth soldiers who fought for Hitler. |

So far, so good. While everyone knows the cameraman is there, they maintain discipline and ignore him. That's what makes the shots work, reflecting the reality that would be taking place in the absence of the cameraman.

However, sometimes the subjects of the photograph notice the photographer (or are posed by him) and commit the cardinal sin of looking directly into the camera when they shouldn't. Below is an example.

|

| Wehrmacht soldiers on the second day of Operation Herbstnebel, known familiarly in the West as the Battle of the Bulge. |

In the photo above, some Wehrmacht troops self-consciously smoke captured American cigarettes in front of an American armoured car. It's an interesting photograph for a number of reasons, not least because it is an obvious propaganda photo intended to show the Wehrmacht's success. However, it stands out because the soldier on the left is looking directly into the camera, while the one on the right is doing everything he can not to look over. If you're trying to capture reality, it's a good idea not to influence it by your presence. The shot screams "phony" because the soldiers couldn't resist the camera. By looking at the camera, the soldier ruins the shot.

Below is another example, this time capturing a typical German column marching through town. Not only the soldier closest to the camera, but also several others, are looking over at the cameraman or woman.

|

| Wehrmacht soldiers in Belgium, 1940. |

In filmmaking, they call this "breaking the fourth wall," which means an actor recognizing that he is in the process of being filmed. Generally, this is considered a cardinal sin of filmmaking, though it is used to great effect in certain situations. One such example was at the beginning of the James Bond film "On Her Majesty's Secret Service" (1969), when new Bond George Lazenby turns directly to the camera after a fight and says, "They never made the other guy [meaning Sean Connery] do that."

Anyway, when you are trying to portray a war, the idea is to have the subject not notice the camera - though obviously they know it's there. That creates the visual that shows how things would be if the cameraman weren't there at all - which is what the cameraman really is trying to capture.

|

| This poor lady just survived a bombing during the Blitz and barely survived - but apparently she notices the camera and gives us her "good side." |

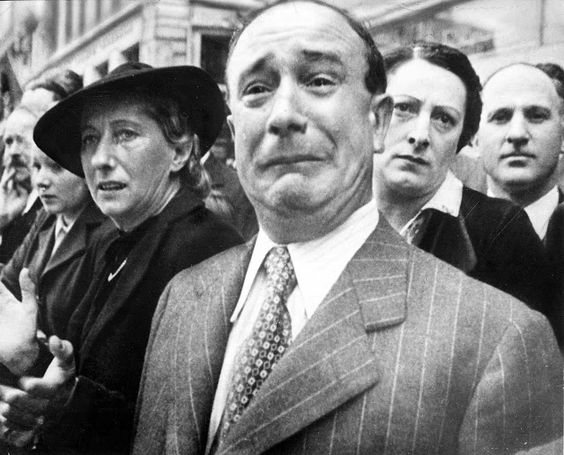

One of the most famous photos of the war, the "crying Frenchman" shot,

|

| The famous "crying Frenchman" picture. |

Now, the "crying Frenchman" picture is one of the most misunderstood pictures of all time, because it is common to call him a Parisian weeping at the fall of Paris, neither of which is true (it was actually part of newsreel footage taken in the south of France months after the fall of Paris). However, what interests us now is the fact that everyone in the frame is looking directly at the camera. In fact, some are craning their necks to make sure they get in the shot. It works because they all all get to share in his emotional outburst, and ratify it. This just goes to show that breaking the fourth wall sometimes works even in war photography.

|

| Female camp guards lined up to be taken to prison. |

In the picture above, what stands out, at least to me, is the fact that the female guard at the right is looking over at the camera even as the other guards stare sullenly ahead. For some reason, this shot works, too, though it isn't nearly as famous as the "crying Frenchman" shot. Probably it works because everyone is looking ahead, maintaining verisimilitude, except for the one rough-looking woman.

Sometimes, the effect can be more subtle, but revealing.

|

| SS soldiers on parade. |

Above, a picture intended to glorify Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler has one of the guys in back giving a suppressed smirk at the camera. Ideally, he would look ahead, but the other guys in the back seat are smirking, too. It's an interesting insight into the attitude of the SS at the time, creating an appearance of overlords with not a care in the world.

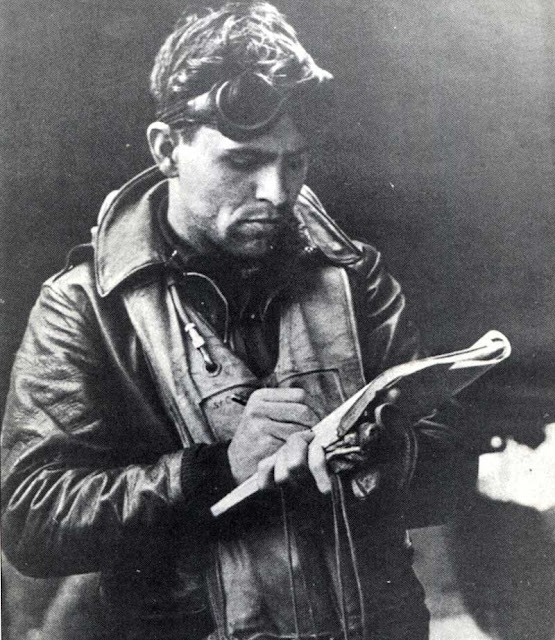

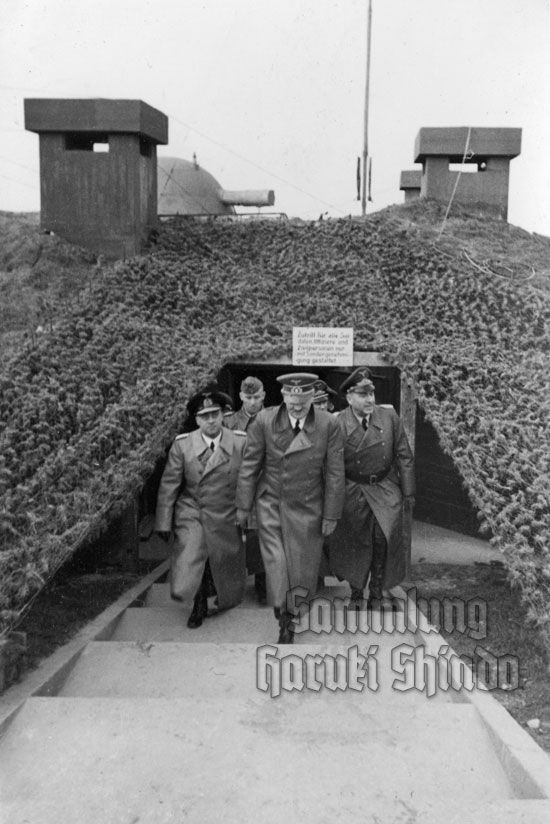

Below is a picture of Hitler inspecting coastal guns along the English Channel on 23 December 1940.

|

| Hitler at Calais, 1940. |

This shot of Hitler in France is obviously posed for the photographer, who had all the top brass bunch up and come up the stairway together. It's an effective shot, but if you look closely, you can see that Hitler is smiling at how silly the whole thing is. If it were a little more obvious it would ruin the shot, but it's so subtle that it doesn't destroy the verisimilitude.

Below, another shot of Hitler from some years earlier.

|

| Hitler and friends. |

This shot of Hitler obviously is posed and everybody intends to look at the camera - or at least in its general direction, because they actually seem to be looking off at a tangent. The striking thing about this shot is that everyone looks extremely self-conscious, almost uncertain. Hitler in particular looks a little uneasy, and it may have something to do with whatever he has in his trouser pocket, which may well be a pistol that legally he shouldn't have.

These shots often create an air of unease.

|

| General Jodl. |

Above, General Jodl gives a withering stare at the cameraman. This was part of a group shot that include Hitler, Jodl, General Guderian, Field Marshal Keitel and several others. This doesn't seem posed - Jodl just decides to look over and see what the cameraman is up to. It's actually a good shot, precisely because it doesn't appear posed but rather spontaneous.

|

| Wehrmacht soldiers preparing to jump off at Kursk, 1943. |

Above, soldiers are ready to jump off at Kursk in the summer of 1943. They're about to get shot at, but they see the cameraman and that takes them out of the moment. It's an interesting example of the power of the camera, which is able to distract guys even as they're about to run out quite possibly to their deaths.

|

| The first female nurse on Iwo Jima, 1945. |

Above, the first female nurse on Iwo Jima makes some new friends. What are the guys on the right more interested in? The camera! Basically, they ruin the shot, stealing attention away from the pretty nurse. In essence, they come off as a couple of delinquents - now is not the time and place, guys. In this instance, if you want to create a good impact - don't look at the camera.

|

| Field Marshal Rommel and others in May 1944 (Jesse, Federal Archive). |

Above, Field Marshal Rommel gives the cameraman a direct glance. Rommel himself was an amateur photographer. By looking at the camera here, he dominates the shot and basically shuts out his two companions, Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz and Gerd von General Field Marshal Rundstedt.

If you're going to look at the camera, though, you have to do it the right way.

Above, a Russian partisan boy looks over at the camera while his elder looks straight ahead, but he probably conveys some things he probably would just as soon not have. He's a touch too wide-eyed, creating a creepy sensation. It does create a striking effect, but probably not in the way intended. It comes off as kind of creepy.

Let's descend one more level of creepiness.

|

| Stalingrad, 1943. |

In the photo above, the soldiers in the foreground are very conscious of the cameraman, and one even is looking at him. However, once you notice them, it is the dimly lit men in the background that steal the shot. They are looking dead on at the camera, and appear terrified. Well they should be - this is after the surrender, and they know that they are all dead men. The cameraman is a Soviet soldier, and there is no escape.

Anyway, sometimes breaking the fourth wall works, and sometimes it doesn't. It's probably not what the photographer was intending, however. The key takeaway is that a basic determinant of how well a shot will work is whether the subjects take notice of the cameraman, how they notice, and who in the shot notices.

2017