An Unexpected Roadblock Led To Critical Failure In Finland

|

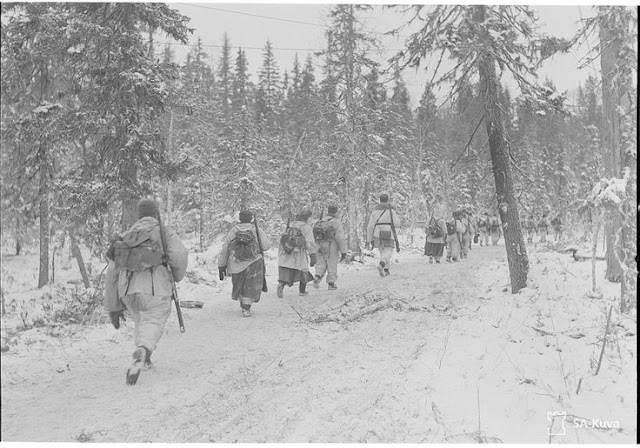

| Finnish ski troops at Petsamo, 14 April 1942 (SA-kuva). |

Did the Germans try to take the northern Soviet ports during World War II?

Taking the northern Soviet ports of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk was a priority Axis goal during the opening stages of Operation Barbarossa. In fact, the failure to take them was the first sign that Operation Barbarossa might not be quite as easy as Hitler and his generals thought.

Finland was never technically an ally of the Reich, despite all appearances. While it declared war on 25 June 1941, Finland more appropriately is classified as a co-belligerent. To the Soviets, of course, this was a distinction without a difference. German land and air forces operated from Finnish territory and the Finnish armed forces coordinated in grand strategy versus the USSR. To the Allies, it looked like the Germans and Finns were working hand-in-hand (and this almost caused the US to go to war with Finland, though it never did).

However, the distinction between “ally” and “co-belligerent” actually made a huge difference in operations. Marshal Carl Mannerheim, the leader of the Finnish military and de facto head of the entire war effort, increasingly showed an independent streak that irked the German high command. This had a major impact on the war effort in the Arctic theater.

It is common knowledge that the Wehrmacht’s main front at the beginning of Barbarossa had three main prongs: Army Groups North, Center, and South. Completely overlooked by many people was the separate effort further north in Finland. In some ways, though, this theater became the most important of all as the war dragged due to its economic impact.

|

| General Eduard Dietl, one of Hitler's favorites due to his success at Narvik in 1940, is seen during Operation Platinum Fox in July 1941 (Witt, Federal Archive Picture 183-B16420). |

This was because the Soviet Arctic ports were the gateway for Lend-Lease supplies to flow into the Soviet Union. The flow of goods along the railway from Murmansk to the south needed to be eliminated to cut off these vital supplies. This could most effectively be accomplished by taking the ports themselves, which were tantalizingly close to the Finnish border (at least on the maps Hitler relied on, which did not show how rough the intervening ground was).

The Germans knew this potential issue before the war began and wanted to “nip it in the bud” in the opening days of the offensive. So, they sent two divisions, the 2nd and 3rd Mountain Divisions, to Kirkenes on the Finnish side of the border. Called Mountain Corps Norway, these two divisions were to first secure the nickel mines near Petsamo and then take Murmansk. This was a huge buildup for such a remote location and their presence took the Soviets completely by surprise. The overall operation toward Murmansk was Operation Silver Fox.

The first part of the operation went off flawlessly. The troops took the Kolosjoki nickel mines, badly needed by German industry, without a hitch. This was Operation Reindeer (Unternehmen Rentier). Led by perhaps Hitler’s favorite general, Eduard Dietl, the mines were secured within a week and remained in German hands until late 1944.

|

| German soldiers in the far north, 1943 (Theobald, Federal Archive Picture 101I-103-0943-13). |

Dietl then began the second, more critical phase of Silver Fox, codenamed Platinum Fox, about a week after the start of Barbarossa. Ferdinand Schörner, a no-nonsense general (later field marshal) known as "the butcher" who famously said “The Arctic does not exist!” when his troops complained about the cold, also made his name in the theater.

However, the Soviets now were alerted to the situation and realized the danger of losing the railway. Even as his fronts further south collapsed, Stalin directed just enough troops up the railway to slow down and eventually stop the Germans well short of Murmansk. The Wehrmacht, it turned out, had issues with the Arctic weather and the rugged terrain, whereas the Soviets had learned bitter lessons from the Winter War. These battles, incidentally, were the furthest north in the entire conflict.

|

| Gun emplacement at Petsamo, Finland, 1942-43 (Grub, Federal Archive Picture 101I-103-0908-06A). |

Stymied in their frontal assault, the Axis then shifted the effort a little further south to cut off the railway. The Arctic ports, after all, would lose most of their value without the railway to ship supplies brought in by ship to the main front. This attack, directed through Salla and Kestenga toward the railway at Loukhi and Kem, required close cooperation between the Finnish and German militaries and came quite close to success.

However, Mannerheim already was getting concerned about the Wehrmacht’s slowing pace of advance on the main front and rising Finnish casualties. The Germans tried to “order” him to bolster his attack toward the railway, but he flat-out refused. They also tried to have him attack Leningrad from the north, but on 31 August 1941 Mannerheim refused.

This was a little-noticed but critical turning point in the entire war. From then on, Mannerheim only made a pretense of attacking and ordered his troops to stop at very clearly defined lines, usually at the original (pre-Winter War) border (or wherever the Finns thought the borders should have been all along). So, Mannerheim repeatedly had his troops stop well north of Leningrad, for instance, and at the Svir River despite the fact that they could have advanced further (especially on the Svir).

At Leningrad, the Finns did some shelling of the outskirts of the city (which the Russians make a big deal about but accomplished little) and some half-hearted “show” attacks that had no hope of breaking the Soviet defenses. It was all just to placate the Germans without actually putting more Finnish lives at risk than was absolutely necessary.

|

| Finnish troops near Kestenga on the road to the Murmansk railway at Loukhi during Operation Platinum Fox, 17 November 1941 (SA-kuva). |

The Germans had limited resources in the remote Finnish areas that were accessible only along snowy trails and it was very difficult to bring more forces and supplies in. Without an extreme Finnish effort, the attacks toward the ports, the railway, and Leningrad bogged down. This failure began a long and convoluted series of German requests that Mannerheim make strong attacks to the east, with Mannerheim repeatedly refusing (in a very courteous way).

Mannerheim’s favorite excuse was to say he would be happy to attack east - once Leningrad had fallen. Since Hitler refused to allocate sufficient forces to take the city, and Mannerheim refused to attack it himself, he had a perpetual “out” in terms of attacking elsewhere. The German forces in Finland were completely dependent on Finnish supply services, so they had no way to compel Mannerheim to do more, and he was happy just to hold what he had obtained in the opening weeks of Barbarossa.

|

| Ferdinand Schörner, April 1941 (Scheerer, Theodore, Federal Archive Picture 183-L29176). |

The final strategy was to bomb the ports, and at this they had some success. However, the Luftwaffe effort in the far north was dispersed between attacks on the ports and on the convoys themselves, and these attacks (primarily by Stukas) had no strategic impact. The Germans even resorted to trying to bomb hillsides to cause landslides because geologists had told them the ground was unstable, which must have confused the Soviets as to why they were dropping bombs in the forests.

So, yes, the Axis did attempt to take the ports and bomb them. It also attempted to cut them off and make them useless. All these efforts failed, and the front turned into garrison warfare with no real effect on the outcome of the conflict.

|

| Finnish border patrol trooper at Petsamo, July 1942 (SA-kuva). |

2022

No comments:

Post a Comment