On this blog, we look at a lot of unsavory characters from World War II. This is one of them. Joachim Peiper.

|

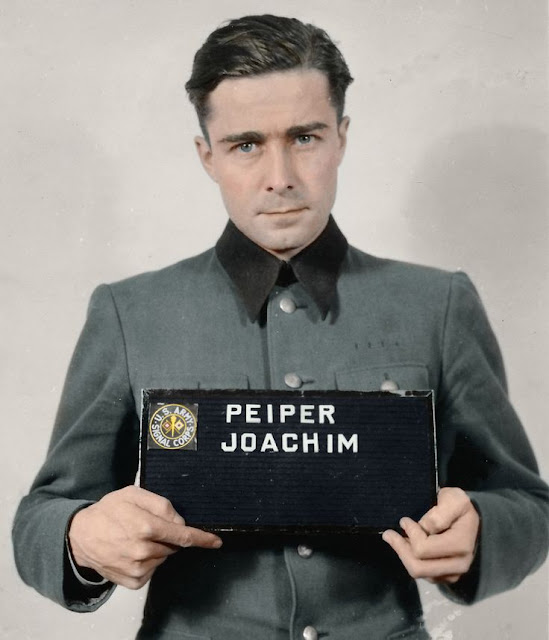

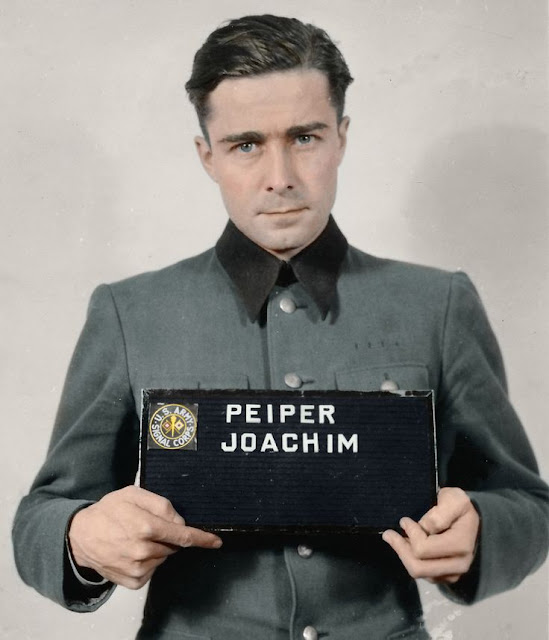

| This Joachim Peiper mugshot was taken at Schwabish Hall prison. |

One of the worst was

Joachim Peiper aka Jochen Peiper, a convicted war criminal who only by sheer luck evaded a death sentence for war crimes.

We look at bad individuals such as these to understand them and their times, not to honor or glorify them.

|

| Joachim (on the right) and his brother Horst, around 1924. |

They were evil, vicious people who are prime examples of what

not to do. Peiper is the subject of intense debate to this day. He was one of those rare Wehrmacht big shots who had charisma in abundance, and it continues to attract followers. Peiper has his fervent defenders and his adamant detractors, and there is little in between. Not only are his crimes disputed by some, but pretty much every detail of his career has an unclear layer of complexity to it with no definitive answer - and that was the case during his life when prosecutors tried to pin crimes on him. In short, Peiper has become a sort of lightning rod about the culpability of an admittedly competent (if vile, murderous, and ultimately criminal) officer in a completely corrupt system.

In brief, where do uncompromising patriotism and effective order-execution end and criminality begin? Because Peiper straddled that line. Perhaps he went way over it. That is for you to decide.

|

| Peiper accompanying Himmler, July 1940. He already has his Iron Cross (Weill, Federal Archive). |

Heinrich Himmler, as head of the SS, surrounded himself with truly brutal and remorseless subordinates such as Reinhard Heydrich, the developer of the Holocaust. One of the more capable sycophants was Joachim Peiper, who rose from being simply Himmler's aide to become one of the key men in the Waffen SS.

|

| Peiper in the rear to the right. He and Himmler do not look happy. Perhaps a concentration camp inspection? September 1940 (Weill, Federal Archives). |

Joachim Peiper (30 January 1915 – 14 July 1976) was born into a middle-class family in what is now western Poland. His father was a decorated Army Captain who served in Turkey during World War I. After the war, Captain Peiper was among the many shiftless army veterans who formed into loose groups known as Freikorps and caused political trouble.

The elder Peiper's military career had developed valuable contacts, such as later-General Walther von Reichenau. Reichenau became a family friend, and his influence no doubt helped Joachim's advancement. Young Joachim was an indifferent student, but he did show aptitude for various pursuits such as sports. It is said that Peiper became a Boy Scout in 1926, though it is unclear if that is an urban legend. The German Boy Scouts ultimately were absorbed into the Hitler Youth in 1933, and Peiper definitely did join the Hitler Youth so it may be true. Peiper followed his brother Horst from the Hitlerjugend into the SS, where Joachim was promoted to Obersturmführer right before the war.

|

| Peiper with his family, father and brother Horst roughly ten years after the earlier picture. Note the close family resemblance. Also note they all are in uniform, even the father - long-since retired. This was a classic military family. |

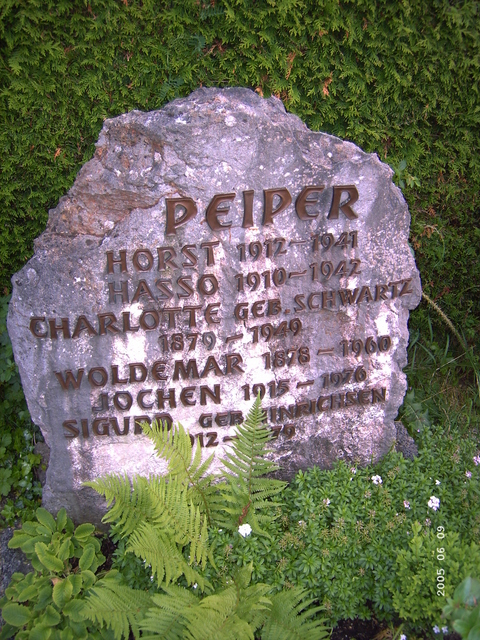

That is jumping a bit ahead of the story, though. As a promising young officer in the SS with connections, Peiper naturally came to Heinrich Himmler's attention. The two developed a relationship of mutual respect, and during the mid-1930s Peiper became one of Himmler's adjutants. During his visits to Himmler's office, Peiper fell in love with Sigurd Hinrichsen, one of Himmler's secretaries (and a close friend of Himmler's mistress Hedwig Potthast). The two were married on June 26, 1939, and had three children: Hinrich, Elke, and Silke.

Note the fact that their boy apparently was named after Himmler, and that, by marrying the friend of Himmler's mistress, Joachim further ingratiated himself with his boss. This all follows a typical pattern of a careerist of any time period. Nothing wrong with that, Peiper wanted to get ahead. But recognize it for what it was.

|

| Peiper is looking up admiringly at the lower right. There are few pictures of Peiper, Hitler, and Himmler in the same shot. Up with Hitler and Himmler is Brigade Commander Paul Hausser, the Waffen SS founder. Peiper usually is cropped out of this shot. Münster, Germany, 1940, watching maneuvers. |

Peiper was all about the SS: it was his whole life, and everything revolved around that. He was a perfect product of the Hitler Youth, though, strangely, it is said that he never actually joined the Party. This point is hotly disputed by some, who claim that Peiper had a Party membership number and that his later denials of party membership were false.

|

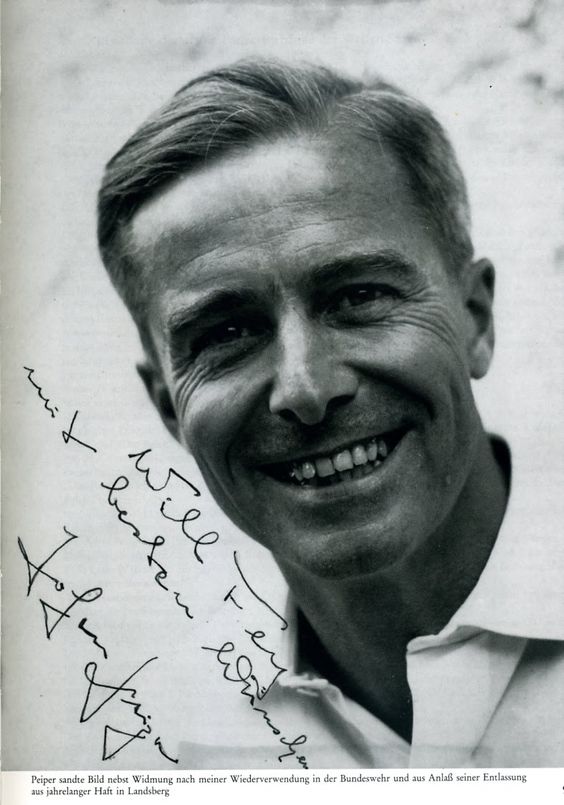

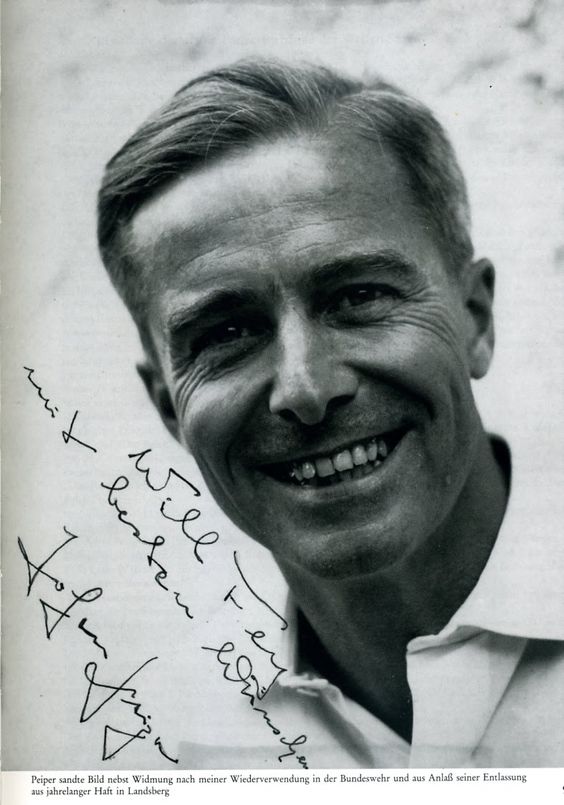

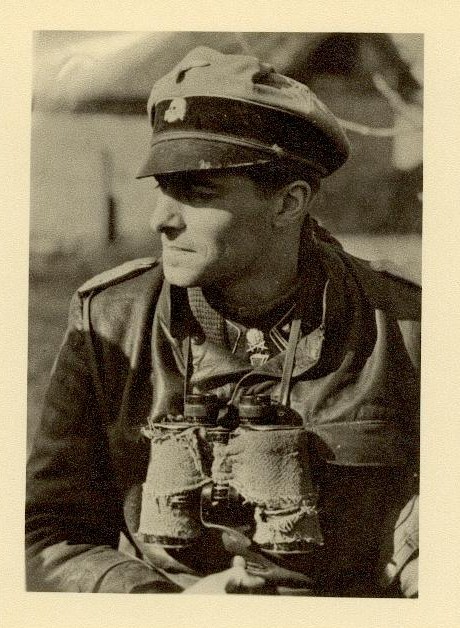

| The Peiper his fans see. |

The discrepancy may be due to his being automatically given a Party membership, perhaps even without his knowledge, when he joined the SS Leibstandarte Division. The stories about his apparent party membership never seem to quite match up with the actual timing of his career, but many believe it got slipped in somehow at some point. He may not even have been told that he had been admitted to the NDSAP, as it would have been a mere formality anyway.

|

| The real Peiper: "I was a [Party member] and I remain one." |

Peiper himself famously told an Italian journalist in 1967:

“I was a [Party member] and I remain one…The Germany of today is no longer a great nation, it has become a province of Europe.”

It is unclear if Peiper was speaking literally when he said that he was a lifelong Party member, or merely figuratively. As in so many instances, we get into shades of meaning with Peiper. His fans will believe whichever side of that particular equation makes him seem more heroic to them, that's how it goes with Peiper in so many ways.

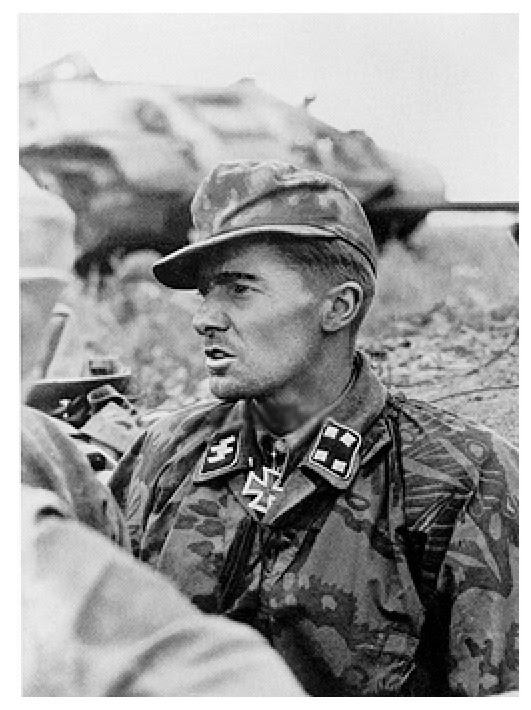

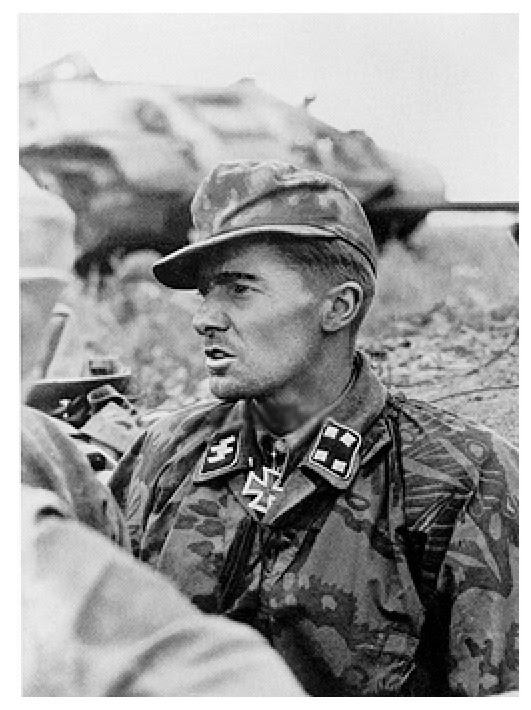

|

| SS-Sturmbannführer Jochen Peiper and SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Rettlinger (Kommandeur 3.Batterie/SS.Sturmgeschütz-Abteilung 1) near Kharkiv, February-March 1943. SS-Obersturmführer Otto Dinse is seen on the right looking to Peiper. The Kharkiv operation was a brilliant success. |

Because of his fanatical devotion to the SS and his supreme dedication, Peiper became one of Himmler's favorite officers. Even after he took up active SS army commands, Peiper repeatedly left them during quiet times and swung back into the Himmler orbit for extended periods. It was an unusual arrangement that worked quite well, giving Peiper battlefield experience and also close and repeated contact with the top movers and shakers in the Hitler regime. Peiper may have seen more variety of the entire war, from actual killing and depredation to austere map maneuvering and political jousting, than anyone else in the Third Reich or, indeed, the world. He was a man of two worlds.

|

| A perfect product of the Hitler Youth. |

Peiper accompanied Himmler on his various inspection tours of Poland on Himmler's personal train "Heinrich." This involved witnessing various mass killings. After visiting some Waffen SS troops in France, Peiper was infused with the martial spirit and asked to join a combat unit preparing for the conquest of France. He was appointed a platoon leader in the 11th Company of 1st SS Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (the "Leibstandarte") perhaps the premiere SS Division. Peiper exhibited heroism during the invasion and earned a promotion and the Iron Cross.

|

| Eyes straight ahead, perfect posture, immaculate uniforms - the SS. Peiper is wearing a Tank Destruction Badge (German: Sonderabzeichen für das Niederkämpfen von Panzerkampfwagen durch Einzelkämpfer), awarded to individuals who destroyed enemy tanks using a hand-held weapon - which required steady nerves and luck. The award was instituted by Hitler on March 9, 1942 for actions on or after the commencement of Operation Barbarossa, so this is mid-1942 or later. I believe it is a silver badge, which meant 1 kill - a gold badge would mean five kills. Not to take anything away from the achievement, and I will likely get blowback for saying this, but it was not uncommon for commanders to pick and choose choice moments to earn such awards for themselves, opportunities not available to common soldiers. It was a little like resume-building. |

After France was defeated, Peiper returned to Himmler's staff on June 21, 1940, where he sat in on top-level meetings with Hitler and other Reich leaders. In this way, he obtained a unique perspective on the war at both the highest and the lowest levels.

|

| Hitler welcomes two children from Deutsche`s Jungvolk at the Berghof. Behind is Obersturmführer Waffen SS Joachim Peiper. |

During this period, he paid further visits to concentration camps, which were not quite yet the death camps they later became (they were bad enough anyway). Peiper was the stats guy, holding the clipboard and giving his boss Himmler facts and figures on arrests and deaths. Courts have held those types of enablers guilty of the crimes committed, but we'll get to culpability later. Basically, he was Himmler's "body guy," there to look after the Reichsfuhrer SS, protect him and serve whatever role Himmler needed. This generally involved wearing an immaculate, parade-style uniform.

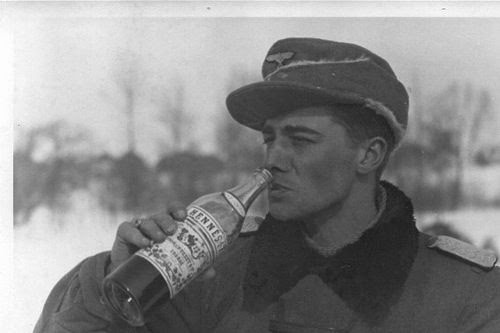

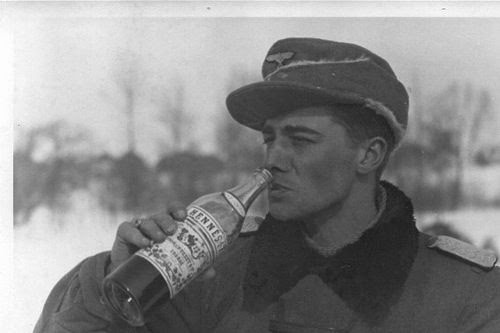

|

| Peiper enjoying some Hennessy, perhaps captured during the Battle of the Bulge. |

Peiper rejoined the Leibstandarte for Barbarossa, which invaded with Army Group South towards the Black Sea area of Rostov. He took command of the 11th Company after his unit leader was killed, and led his men into some hell-for-leather combat. They incurred tremendous casualties and killed Russian prisoners of war - not uncommon on either side, but still an early indication that Peiper had adopted the wrong lessons somewhere along the way.

|

| I do not have a date for this shot, but will take a wild guess and say that it was when Peiper was the 377th recipient of the Oak Leaves on 27 January 1944 as SS-Obersturmbannführer and commander of SS-Panzer-Regiment 1 "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler." |

The unit assisted an accompanying Einsatzgruppe with its liquidation activities, also not terribly uncommon. His troop either loved him for his total dedication or resented him for pushing them repeatedly into deadly situations and leading a huge fraction of them, relative to other formations, to their deaths. But other leaders did that, too.

|

| Peiper at Kursk. By now, the situation was getting grim. |

In May 1942, the Leibstandarte was transferred to France and Peiper learned that his brother had died. Peiper effectively returned to Himmler's staff for a while - being Himmler's buddy gave him tremendous freedom - then rejoined his unit in August 1942. He was promoted to commander of its 3rd Battalion, and Peiper himself recruited within France for new soldiers just like himself. Early in 1943, he was promoted to SS-Obersturmbannführer, after which the Division returned to the Eastern Front. It was time for a showdown with the Soviets, and all hands were needed on deck.

|

| Note the immaculate dress uniform, everything neat and tidy. Peiper was relatively unique at being both a front-line soldier and a spit-and-polish adjutant. |

Peiper began establishing his reputation during the Third Battle of Kharkiv when the SS retook the city after losing it in the flight after Stalingrad. He drove his battalion across a river to rescue some trapped troops of the 320th Infantry Division, then repaired a bridge enabling ambulances to return to Germany. However, because the bridge was unsteady, Peiper led his men back through the Soviet lines to find another escape route so that he did not lose his heavy equipment. In other words, to find a way to retreat, he first had to advance further into enemy territory

i.e. the wrong way. That took guts. He brought his men around through the Soviets, found another way across the river, and eventually made it to safety with his command and equipment.

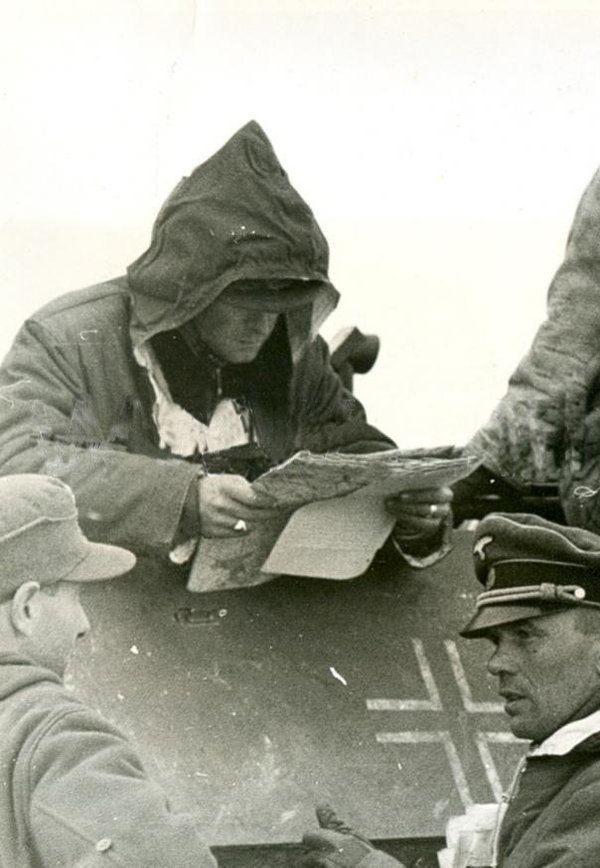

|

| Peiper and Heinz von Westernhagen (commander of Leibstandarte Sturmgeschütz (Assault Gun) Battalion), vicinity of Kharkov, Feb-Mar 1943. |

All this heroism made Peiper popular with his comrades. It also won Peiper the Deutsches Kreuz in Gold. His name began to appear in the German press, with his unit referred to as "Kampfgruppe Peiper" (Battlegroup Peiper). That was a tremendous honor and made him famous. It began the "Peiper Legend," an important tool to improve homefront morale. People desperately wanted to believe that the war was going well and Wehrmacht soldiers could fight off the Soviets. Making heroes of front-line commanders like Peiper fit the bill.

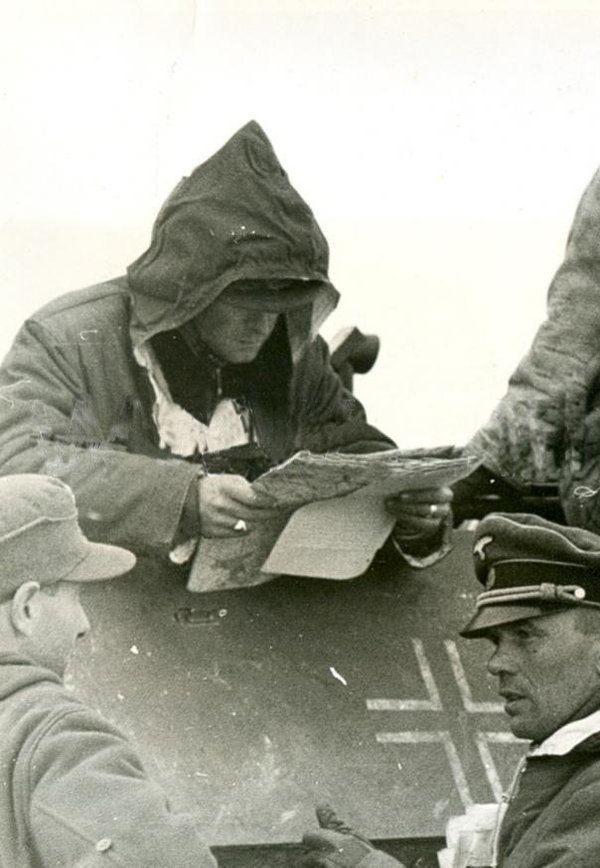

|

| Peiper is not letting the intense cold bother him when talking to a fellow officer in the snow. Peiper may not be wearing his cover, but otherwise, he is immaculately attired. Incidentally, if you look very carefully between the two men, you will spot a sign with "Peiper" scratched on it - probably used to direct follow-up forces toward his advance location, and also to mark his headquarters. |

The Leibstandarte remained in the line for the battle of Kursk, where Peiper again did well. However, overall the Kursk operation was a strategic failure for the Wehrmacht, and Hitler needed to deploy the tremendous firepower spread out over the Russian steppes there elsewhere.

|

| Peiper in the Kharkiv sector, early 1943. |

Peiper was transferred to Northern Italy due to the invasion of Sicily. Hitler said that he needed "politically reliable" men in Italy, and there were few more politically reliable men than Joachim Peiper.

By now, Peiper's unit was completely hardened and ruthless due to conditions on the Eastern Front, and they had developed bad habits. In reprisal for various partisan activities, it allegedly set fire to a village and killed 22 men, including two who had been helping his unit (the "Boves massacre"). A trail of criminality always seemed to follow Peiper's units, but his defenders never see any connection there.

|

| Leibstandarte soldiers at Kursk. |

Peiper denied any criminality at Boves, and in fact, claimed that his men's actions were necessary to prevent an Italian attack on his positions. That explanation was quite suspect, but to Peiper, any depredations were fine if they helped his unit in the slightest.

|

| You did not want Joachim Peiper frowning at you. Someone is about to get shot. |

The Leibstandarte then returned to the Eastern Front once again around Zhytomyr. The Germans launched a successful but short-lived counteroffensive there. Zhytomyr, incidentally, was an Eastern Front headquarters of the SS, and the SS fought doggedly to recapture and retain it. If you closely study operations on the Eastern Front after Kursk, you will see that the November 1943 Zhytomyr operation was one of the very last spirited offensive operations by the Germans of any consequence, and the location of the SS HQ there is the reason. Such things are a matter of pride.

Peiper received the Oak Leaves of the Knight's Cross at this time, a very high decoration. Peiper's men burned down villages (as in Italy) and took very, very few prisoners, repeating a common pattern. It was the Eastern Front, though, so few noticed.

|

| Peiper receives a military decoration from the hand of Hitler at the Wolfschanze, Feb 1944. |

In January 1944, Peiper was promoted to Obersturmbannführer, then in February received an award from Hitler's hand. After that, he went home for a long rest with his wife in Bavaria. Peiper did not rejoin his unit until April 1944. After that, while stationed in Belgium, Peiper had five of his men shot for stealing food from civilians. That undoubtedly was due to the soldiers' breach of discipline, which was sacrosanct in the SS, rather than concern for the civilians. However, it was respectful to the notion of some kind of rules, a sort of curious legalism. It demonstrated Peiper's absolutely rigid adherence to his own code of conduct, distorted as that may have been by an attitude of "the ends justify the means."

|

| Peiper leading his Kampfgruppe during the Battle of the Bulge. His advance was dependent upon crossroads through the forest. Here he is between St. Vith and Malmedy, both key junctions, one the site of a famous massacre by his men. That appears to be an amphibious vehicle, a Schwimmwagen. You can't see it, but there is a fold-up propeller in the back. |

When the Allies invaded Normandy on June 6, 1944, Peiper and his men joined the defensive line. The division fought hard as always and lost a quarter of its men. It became a Kampfgruppe, the official term for a remnant of a division. Peiper had a nervous breakdown and spent much of the time in a hospital behind the lines, staying there until October. It was then that Peiper began preparing for the operation that would cement his name forever in the history books.

|

| Sepp Dietrich, Hitler's former chauffeur who became an SS General. |

The Germans had more or less held the Allies to a standstill throughout the fall of 1944, and Hitler saw an opportunity to mount a counteroffensive from the Ardennes forests toward the key port of Antwerp. He hoped to repeat the success of May 1940, this time against the Americans and again cut off and surround the British to the north. SS General Sepp Dietrich commanded the 6th SS Panzer Army and was responsible for establishing a breakthrough.

Battlegroup Peiper in the Ardennes

Peiper was chosen to lead the premier striking force in (Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein ("Operation Watch on the Rhine")). The operation was an ill-advised German offensive that was only possible due to a period of relative quiet on all fronts. "Wacht am Rhein" was renamed "Herbstnebel" ("Autumn Mist") in early December.

Battlegroup Peiper was the most powerful out of four separate battlegroups, and it had the most critical objective: capturing a bridge intact over the Meuse and holding it for the rest of the Heer. The plan was that, rather than constituting simply the tank raid that it turned into, the Peiper advance would smooth things out for those that followed.

Peiper knew that this operation was Germany's last real chance. As recalled in 1946 by a SS Hstuf. Gruble, Peiper had

this to say in the order he issued for the offensive (which apparently originally came from Sepp Dietrich):

"The German nation has lined up for its last big fight. The objective is Antwerp and to break up the Allied forces that have lined up in the Aachen area. The German nation expects from its soldiers the greatest preparedness for action, courage and sacrifice. The people will not welcome our advance in whose territory we carry out the fight. Any resistance from this quarter and any acts of terror will be countered with the greatest ruthlessness. This fight will be conducted stubbornly with no regard for Allied prisoners of war who will have to be shot if the situation makes it necessary."

The battlegroup incorporated the most advanced Tiger II tanks and had about 5,000 men, basically a brigade (though, at that late stage of the war, it was about the size of a normal division). The attack began in bad weather on December 16, 1944.

Kampfgruppe Peiper made quick progress. While the attack fell behind the overly ambitious schedule almost at once, Peiper kept as close to it as anyone in the entire offensive. His troops scored a major victory early on when they captured 50,000 gallons of gasoline for his vehicles - necessary for the advance and a part of the operational plan (and a key weakness of that plan). Peiper's men advanced ahead of the entire army group, making detours when necessary due to bad roads and bridges and wiping out the opposition. Part of this "wiping out" occurred in the infamous "Malmedy massacre," in which Peiper's men took captured Americans into a field and machine-gunned them (a couple survived, including later-famous actor Charles Durning).

Malmédy Massacre

There are some graphic images in this section.

The Malmedy massacre deserves its own section because it is the major reason for Peiper's infamy. In brief, Peiper was tasked during the Ardennes offensive with impossible objectives by the OKW, but he came closer than anybody at fulfilling them. The offensive was in full swing on 17 December 1944, but even then, the second day, it was behind schedule. Fighting in the Ardennes with armored troops was almost equivalent to a naval battle: everything depended upon subduing islands of resistance at crossroads. Bastogne was one such crossroad, and it was never captured; Malmedy (or rather about five miles (8 km) south of there, at the Baugnez Crossroads, where five roads intersected) was another.

US soldiers of Battery B of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, a lightly armed technical unit, were retreating from Malmedy south through the crossroads. The location is always referred to as Malmedy, but in actuality, it was along the road between Bullingen and Ligneuville, about 8 km (5 miles) from Malmedy. I take great pains to make this distinction because someone from Malmédy contacted me about this and expressed indignation that his town is continually linked to this tragedy when, in fact, it occurred... 8 km (5 miles) south of there.

The traffic that day was an ordinary US convoy of jeeps and trucks, with an MP directing traffic. Nobody knew where the Germans were, but everybody knew they were on the way, so the Americans were bugging out. Peiper's men suddenly erupted out of the woods from another road and a fierce battle ensued. When some of the out-gunned Americans took refuge in a tavern, Peiper's men set the building on fire and gunned down everyone leaving it. The resistance ended quickly, as it was men with rifles against German tanks. Peiper was on the scene, but he was pressed for time and troops. He had his men stand the surviving Americans in a snowy field next to the burned-out tavern. He had them guarded by only a few SS troops, including some non-German ones. Then, Peiper and his convoy left and headed down the road for Ligneuville and, later to Stavelot.

The Americans stood shivering in the cold. They had every right to expect to be treated humanely in accordance with the Geneva Convention. The SS stood looking at them, but there was no transport and there did not appear to be anywhere to go. Something was different this time.

What happened next was the subject of dispute at trial. There are two versions because there were two groups of people who gave their accounts later: the SS guards, and the surviving POWs. The guards said that: one or more prisoners made a break for it; a guard fired a warning shot or two, and then the prisoners all ran for it at once. The guards then claimed that they "had" to open fire.

The POWs, on the other hand, said the guards just waited until Peiper was out of sight and started blasting. Those that ran were simply fleeing for their lives from the murderous gunfire. The court believed the POWs, but some will always take the side of the perpetrators.

What is certain is that, once Peiper's column was gone, the SS opened fire on the defenseless prisoners. Pvt. 1st Class Georg Fleps, a Waffen-SS soldier from Rumania, was identified as the first to fire a shot. As noted above, what purpose he had in mind in the firing was the subject of intense disagreement at trial. The result, though was obvious. Within a matter of moments, 72 defenseless American soldiers lay dead or dying in the snow from machine-gun bullets. Only three survived. The field was open, with few trees, and the POWs had nowhere to run to. The SS account was greatly undercut by the fact that the guards later went around to the prisoners who were lying helpless in the snow but still breathing and administered "kill shots" to their heads.

The majority of the corpses of the murdered GIs were eventually shipped back to the US for a private burial. Twenty-one, though, still lie buried in the American Military Cemetery at Henri-Chappelle, about forty kilometers north of Malmédy.

|

| Peiper (right center, blowing smoke) leading his troops near Malmedy. |

It is important to note that the Malmedy massacre was not the only alleged war crime incident involving Peiper's men during the Ardennes offensive. In fact, they were accused of murdering between 538 to 749 nameless Prisoners of War and more than 90 unidentified Belgian civilians during the operation. There is no question that Peiper either encouraged or condoned a spirit of lawlessness in his troops, and there was testimony that he had told his men to take no prisoners (exactly what that meant is disputed). What the few SS men were supposed to do with the American POWs in the field if they hadn't shot them was never explained.

Peiper had this to say much later:

"It's so long ago now. Even I don't know the truth. If I had ever known it, I have long forgotten it. All I knew is that I took the blame as a good CO should and was punished accordingly."

Some would like to place Peiper miles away throughout the entire incident and having nothing to do with it. That would make no sense. Peiper was advancing at the head of his column and was in total command throughout the operation. He had just left the massacre site when it took place. If his men did something in his extremely disciplined unit, it was with the understanding that Peiper wanted it that way.

The Offensive Runs Tight

Fighting intensified, and Peiper's advance thrilled the German public, with his superiors telling him that the "eyes of Germany" were on Battlegroup Peiper. The unit continued forward along the Ambleve River. Peiper's men took Stavelot the next day, and then Trois Points, but the American defense stiffened there and around La Gleize. American engineers blew up a bridge over the Ambleve that Peiper required to continue toward the Meuse. After December 19th, Peiper was stuck in a defensive battle that he could not win, and he also could not be re-supplied.

|

| Peiper decorating a grunt with a medal at Kursk. |

Eventually, the weather cleared, enemy airstrikes destroyed many of his vehicles, and the enemy closed in. It was a perfect illustration that armies are integrated units that win or lose as a whole. Peiper had outrun the rest of the army, something that would not have happened if the entire Ardennes Offensive had stuck to its timetable as closely as Peiper. Finally, on December 24, 1944, Peiper was forced to abandon his vehicles and return to German lines with only 770 men out of the 5000 with which he started out, which he managed to do. His troops had made the furthest advance in the offensive, which already had failed. A character in "The Battle of the Bulge" (1965) starring Henry Fonda appears to be very loosely based upon Peiper, a fanatical tank commander who, unlike Peiper, perishes during his attack.

|

| Peiper receiving his death sentence, silently. He then turned in the correct military and professional fashion and marched out. No words, no emotion, nothing. Expected, understood. That's it. As Peiper later said, he took the punishment due to a leader in such circumstances. |

Peiper received further decorations after the Ardennes Offensive failed, but by now decorations were less important than victories. He continued leading his men, including in the final, abortive German offensive "Operation Frühlingserwachen" (Spring Awakening) in Hungary, but the war soon came to a close. Peiper evaded capture for a while, but he was picked up near his home on May 28, 1944, and imprisoned at Dachau concentration camp.

|

| Peiper on the stand for war crimes at Malmedy. His translator is beside him, but Peiper spoke English well. |

The Americans eventually learned his true identity on August 21, 1945, and he was brought to trial for war crimes. The chief prosecutor, called the Trial Judge Advocate, was Lt. Col. Burton F. Ellis who was new to courtrooms. The defense lawyer was Lt. Col. Willis M. Everett, who couldn't even speak German (and thus a translator was required throughout). Despite the language differences, Peiper struck up a sort of friendship with both men - another instance of that charisma at work. One can see it at work in film clips from the trial, where Peiper is extremely solicitous of his translator's difficulties and seems gallantly distressed that he can't help her more. In a colloquial sense, we might say that Peiper was a charmer - one with an underlying streak of extreme cruelty.

|

| Joachim Peiper at an ODR (Ordensgemeinschaft der Ritterkreuzträger) reunion (holders of the Knight's Cross) in 1958 in Regensberg. Shown from left to right are Heinz Lammerding (Das Reich), Ernst August Krag (Das Reich), Peiper (Leibstandarte), and Ernst Barkmann (Das Reich). Barkmann and Peiper served together briefly in 1945. |

All of Peiper's charms, though, could not help him at trial. Peiper was convicted and given the death sentence, which he appeared to expect. However, it was an unusual time for justice. There was a rapprochement between the Western Allies and West Germany in those years due to the perceived Soviet threat. This fear of Stalin - the same fear reportedly felt by Hitler, incidentally - undoubtedly contributed to the commutation of many war criminals' sentences, along with a general sense that war is hell and it was just time to move past it. In the immediate post-war years when big names such as Hermann Goering were on trial, Peiper was a relatively small fish to fry, and nobody in the public seemed to be following his situation very closely. His sentence was eventually converted to life imprisonment, then Peiper was released on parole for time served.

Peiper After the War

Peiper walked out a free man on December 22, 1956, the last of the accused to finally leave Landsberg Prison. He was not the last German prisoner of all, though: some of the Party bosses such as Albert Speer remained in Spandau Prison for another decade, and Hitler aide Rudolf Hess remained there until his death in 1988. However, Peiper was one of the last "small fry" to get out.

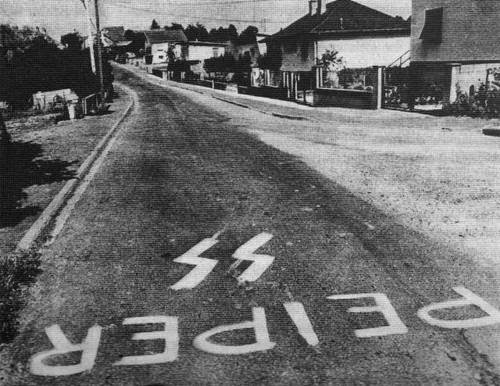

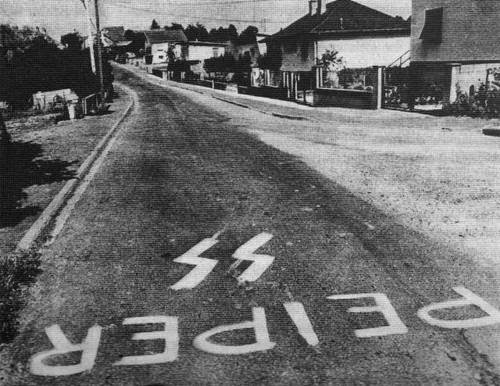

|

| Marked for death: some folks drew this on the road to Peiper's French house. It was later scrubbed clean, but the point was made, here and elsewhere in the village. |

Peiper had great difficulties adjusting to civilian life, which he had never really known. He worked at some auto manufacturers, but he retained his old sympathies, and his reputation caused problems. He was charged anew with the Boves massacre, but, after three interrogations in Stuttgart, ultimately cleared. All the bad publicity and stench of wartime brutality caused Peiper to become unemployable. However, Peiper's difficulties were not simply a question of his past service in the Wehrmacht. One co-worker who knew Peiper around 1962-65, Lothaire Junghans, had

this to say:

"On the surface he was very friendly, while he made scathing reports to the management.... He did not seek to hide the fact that he had been a Colonel in the Waffen SS, but he continued to be a proponent of [German] propaganda. He teased incessantly those who professed, as I, democratic views. And he made fun of those who do not have blonde hair and blue eyes, telling them that they did not belong to the Aryan race. He remained a ... fanatic."

Peiper apparently got along well with many co-workers, and perhaps this Junghans just disliked Peiper for political reasons. However, if Peiper did act this way, it is easy to see why he had some issues fitting in.

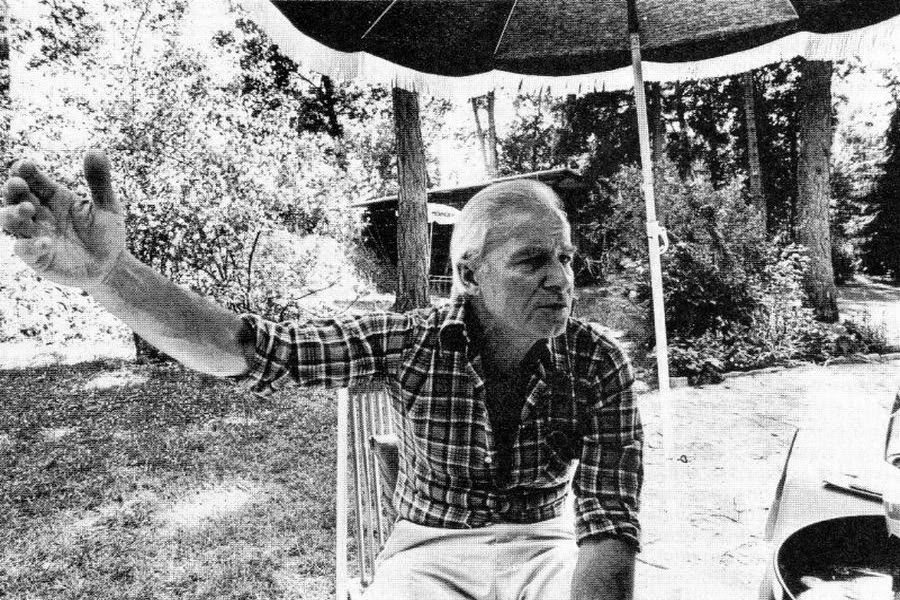

Finally, for some reason, Peiper moved his family to Traves, France. It seems odd that such a notorious figure would go to live among a populace where he had been accused of war crimes, but Peiper was an in-your-face type throughout his life. Peiper lived openly but quietly, mostly avoiding controversy and notoriety and perhaps just wanting to be left alone. In 1976, though, he gave an interview where he seemed proud of his wartime past, and that seemed to set the final act in motion.

|

| Peiper in 1957. |

Local Communists - perhaps not all locals, and perhaps not all Communists, but that is how it is reported - decided enough was enough and determined to kill Peiper. It may not have been entirely political; Peiper's presence probably depressed nearby property values and made neighbors fearful. There also may have been some with personal grievances. In any event, Peiper learned of their plans, sent his family home to Germany for safety, and then awaited his fate. It is said that he prepared for this final battle as he did his military operations, with efficiency and precision. It was not enough to save him, and he probably realized all along that it wouldn't. On July 14, 1976 - Bastille Day - the assassins burned down Peiper's home with him in it. Nobody was ever brought to trial, and Peiper's charred corpse was found with weapons of his own, ready to fight back. The coroner's report said that he had been shot through the head; the fire was probably to cover it up, or just make a statement.

|

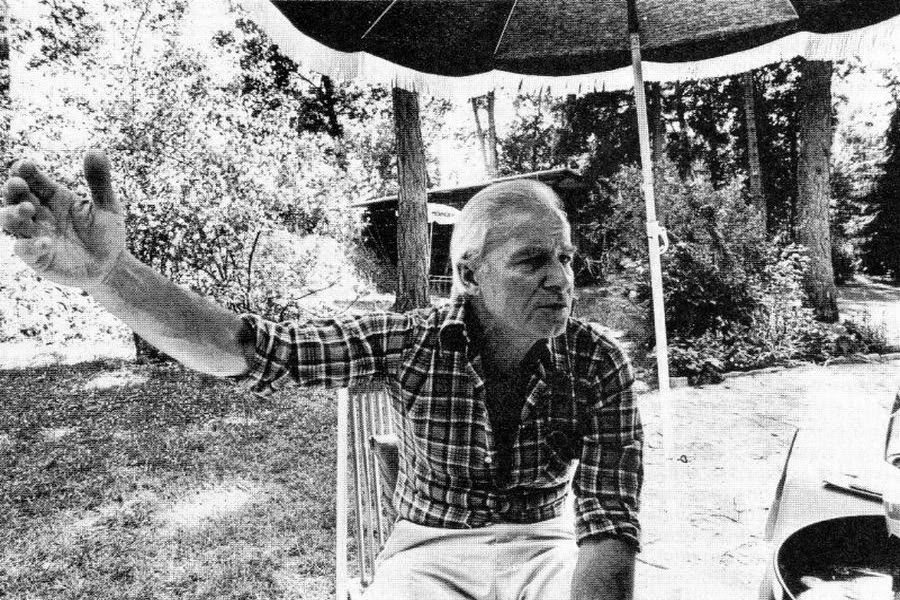

| Peiper a few weeks before his death in 1976. He is shown giving an interview to a journalist after years of seclusion. Perhaps this sudden publicity blitz contributed to the decision to kill him? |

It is impossible to read someone's mind or to psychoanalyze them at 40-year's distance. I will hazard a guess, however. Peiper had been tormented ever since the war for, as he saw it, doing his duty, and doing it magnificently. The haters don't hurt you to your face; they paint Swastikas on the road or they get you fired or they whisper behind your back or whatever little thing they can do to hurt you without giving you a chance to fight back. At last - at long last - Peiper had the chance to face them openly. They let him know it was coming - assassins sometimes like to do that to magnify the terror - and that perversely gave him that final emotional release. Live or die - almost certainly die, as he was well aware - he had one last chance to strike back while he was still able and to show his contempt for their hatred, for their lack of forgiveness, for their barbarity. Then, he sat and waited, armed and ready, a man ready to go down fighting... until it came.

|

| Which Peiper? This is about you... |

|

|

| ... more than it is about him. |

|

It was the personal Götterdämmerung of Joachim Peiper.

Joachim Peiper was a product of his time, the ultimate Hitler Youth who never learned the difference between right and wrong. Peiper, as an uncompromising and ruthless warrior, unfortunately, has become a symbol for many devotees who are quick to make excuses for what he did. Ultimately, though, Joachim Peiper was just a vicious and sad man, deprived of a normal life from childhood due to his training, who due to his ambition lived to hurt and kill others.

|

| The courtroom at Dachau where Peiper's trial took place. |

Below is a film clip with key moments during Joachim Peiper's trial. A few things stand out. First, he helps the translator at times - he was no idiot, he understood English, though he testified in German. Second, his tactic was to shift blame for the Malmedy massacre to Skorzeny's men in Operation Greif, the cloak-and-dagger operation to impersonate Americans. He claimed that he was not present at all and that Skorzeny's men must have done it.

|

| Peiper in the dock, lower right. He would have been mortified if he wasn't in the front row, for sure. |

- 11. Josef "Sepp" Dietrich

- 33. Fritz Kramer

- 45. Hermann Preiss

- 42. Joachim Peiper

- 8. Manfred Coblenz

- 13. Arndt Fischer

- 19. Hans Gruhle

- 23. Hans Henneck

- 31. Gustav Knittel

- 34. Werner Kuhn

- 39. Erich Munkemer

Third, Peiper tried to justify the killings at the Malmedy massacre on the argument that British commandos did the same thing routinely to German soldiers. Fourth, he marches out of the courtroom after receiving the death sentence without a word, maintaining precise military bearing and head held high, not even waiting for the German translation to conclude. Perfectly composed at all times. Again, his charisma is on full display.

The photos below are from a new soldier introduction to the Leibstandarte in Hasselt, Fiandre, Belgium, May 1944. This was an elite formation that had a long and colorful history in the field after its origins as Hitler's personal bodyguard.

|

| Peiper is the one speaking. This kind of speech was no joke - you stood at attention and you did not make faces or anything like that. The talk no doubt had something to do with how only the highest performance and duty was expected of anyone in the Leibstandarte, and that Peiper would personally shoot anyone who disgraced the unit. SS units adhered to extreme discipline. |

|

| Joachim at his trial (Colorized). |

2020

Great work!

ReplyDeleteThanks, TJ.

DeletePeiper Was An Honorable Man Who Deserved Better Treatment After The War ! The Criminals Are Those Who Killed Men After WW II ..... As They Did Peiper and Ickmann and Others

DeleteWHAT a load of old baloney!! Peiper was a hero, if he had been wearing the uniform of the British or U.S there would be monuments made in his likeness, he was that great! This article is pure viciousness.

ReplyDeleteThanks, I was worried I had been too even-handed on him. You've set me at ease about that. I appreciate it.

DeleteAgreed, this is a stupendously uninformed article. Peiper was a brilliant and courageous commander. He was 12 miles away from where the americans were killed in Malmedy. The us army was putting on show trials after the war because they hated the Waffen-SS so much. The prosecuting attorney even told Peiper he believed he was innocent before the trial.

DeleteIt doesn't matter how far from the scene Peiper claims that he was. Peiper was their commander and he was responsible for their actions. Creating a climate of lawlessness that did not exist elsewhere except in isolated situations was Peiper's responsibility. As for the Americans and their "show trials," the Russians would have carried through with the death sentence. As it is, Peiper got off exceedingly lightly, as did so many of the war criminals (let us emphasize that Peiper was a convicted war criminal) during the 1950s "rapprochement" between the Western Allies and the West Germans. Peiper's troops knew what was acceptable to their commanders and what was not, they no doubt learned bad habits on the Eastern Front - where they should have known better, too. No, Peiper deserved to be convicted, that was not a particularly close call, and the actual conviction was never rescinded. He died a convicted war criminal.

DeleteThe Americans were shooting any SS they could get their hands on because they were hopped up on years' worth of Hollywood and government propaganda about the "evil Germans." That's what created the "climate of lawlessness." Furthermore there is plenty of proof that the american POWs were trying to escape when they were shot. How would americans or bolsheviks react to German POWs trying to escape? You think they'd let them go?

DeleteAnd what do you mean Peiper's men should have "known better" from the Eastern Front? The bolsheviks were absolute monsters. Captured Germans were mutilated, disemboweled, sodomized with bayonets, gelded, etc. bolshevik partisans were massacring civilians and spreading terror throughout the countryside. The NKVD executed scores of Russians who refused to fight. If the Germans were cruel on the Eastern Front it was because they were facing pure evil in the form of Stalin's minions. Let's have some perspective here.

Well, you have an interesting perspective on this. Far from the Americans being evil terrors, the Germans by 1945 practically saw them as a relieving army as compared to the Soviets. German formations were fleeing westward as fast as they could walk because the Americans were treating Germans so mildly.

DeleteThe "plenty of proof" to which you refer was the defense's claim that the Americans started running thus the SS guard fired a warning shot, which then turned into a mass escape attempt, which then became a slaughter. The court did not buy that argument, but I did at least say in the article that there were differing views on what instigated the slaughter.

As for the Eastern Front... there was savagery on both sides. I'll leave it at that. The Soviets were not signatories to the Geneva Convention, so the Germans tended to act as if there were no rules of war whatsoever. The Soviets returned the favor. Many ordinary Wehrmacht soldiers were disgusted b SS barbarity. Bringing that savagery to the western front was what got Peiper and the others convicted as war criminals, the Soviets probably would have shot him just for being in the SS.

You forget one thing: no one asked for lebensraum. The germans did.....

DeleteYou forget one aspect. The germans voted for lebensraum. They got it....

DeleteYou forget another aspect nobody only 30% of the people voted for hitler

DeleteIt is rather utter nonsense, as with barely 30% oe could not came into such power, you can not overrun 70% opponents in a free voting system. So, no, it was obviously not only 30 %

DeleteA fine article.

ReplyDeleteLest we forget, if not for Germany there'd have been no war.

Nice article.

ReplyDeleteLest we forget, if not for Germany there'd have been no war.

Lest we forget, Peiper's men killed and raped civilians at random in the small village of "La Gleize" where his advance came to a halt. And by the way, the port that Hitler's armies tried to recapture was not Rotterdam (too far up north) but... ANTWERPEN.

ReplyDeleteAbsolutely nonsense... In La Gleize near the present museum December 44 and a church with small cemetery Peiper had his HQ at that very moment.

DeleteI am an American and have read obsessively on Peiper every book and article i could find. The above article has many errors and is extremely biased. One should read letters Peiper himself wrote as well as his what his soldiers said to get a more fair assessment of his character. Also one should read the statement the prosecuting attorney Burton Ellis wrote to his wife about Peiper and told Peiper himself.

ReplyDeleteAll errors are my own, and I strive to keep everything as factual as I can. If this article leads anyone to further study, I consider that a sign of its success.

ReplyDeleteAs to the tone of my article, which is not meant to be comprehensive because it is not a book with every little detail included, but rather a summary of a famous figure.... I stand by it. Thanks for commenting.

I have a blow-torch ditched at La Gleize by Peiper's men. It came from a Tiger II tank. It was retrieved by a Belgian farmer, and purchased by a French military collector, who sold it to me. His battalion in Russia at one time was known as "The Blowtorch Battalion" for its penchant for burning down villages that gave any resistance.

ReplyDeleteIt is worth to meant :"During the Third Battle of Kharkov, Peiper led the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Panzergrenadier Regiment, which broke 48 kilometres (30 mi) through Soviet lines to rescue the encircled 320th Infantry Division. In a letter home, Peiper described hand-to-hand fighting with a Soviet ski battalion in an effort to lead the division, including its sick and wounded, to safety.[50] The rescue culminated with a fierce battle with the Soviet forces at the village of Krasnaya Polyana. Upon entering the village, Peiper's troops made a terrible discovery. All the men in his small rearguard medical detachment left there had been killed and then mutilated. An SS sergeant in Peiper's ration supply company claimed that Peiper responded in kind: "In the village, the two petrol trucks were burnt and 25 Germans killed by partisans and Soviet soldiers. As a revenge, Peiper ordered the burning down of the whole village and the shooting of its inhabitants".[51] (The testimony was obtained on 17 November 1944 by the Western Allies)" ...

DeleteA massive war crime was committed at the Rhine Meadows death camps established by the allied forces right after the war, Why is it you hear very little about it. I myself served in Germany from 1952 until 1954, I only found out about it years later by searching the Internet, this criminal action was covered up for many years, to my knowledge it was never reported in the western media. This crime IMO, was worse than any committed by the German Army or the SS in my view. Do a search "Rhine Meadows Death Camps"

ReplyDeleteEn cualquier caso todas las guerras traen asesinatos de todos los bandos habidos y por haber, hoy actualmente en las guerras que ocupan casi medio mundo se siguen cometiendo, lo que ocurre que algunos se silencian y otros se airean, de esto saben mucho los americanos en Vietnam.

ReplyDeleteEso es verdad. Sin embargo, el salvajismo desenfrenado no te ayuda militarmente. También invitó a represalias y ennegrece su nombre.

DeleteHistory is written by the victors tainted as that might be if Germany had won the war Peiper would have traded places in history with Patton

ReplyDeletewhat a hate filled article. Half of this stuff is

ReplyDeletepure lies. You had an agenda writing this just look how you start it - "They were evil, vicious people who are prime examples of what not to do." WOW

you are not a tenth of a man Peiper was.

Absolute lap dog for the jews.

My name is Derek, and I'm from Foxboro, MA 02035 in the capitalist U.S. I've watched countless video's, read countless articles and books, and thoroughly studied the infamous Standartenfuhrer Joachim Peiper from a neutral perspective. My conclusion is that Peiper was and to this day will always be my "Hero" ! Any soldier or normal man should look up to Peipers achievements in Shock and Awe ! The fact Peiper was able to survive on ALL fronts with how aggressive he ran his blowtorch battalion at the enemies is a feat in itself! He was truly fearless,brave, and in a way almost robotic and non-human! Although I know he suffered a personal nervous breakdown at the end of the war, but who wouldn't when you are fighting for your country,comrades, and survival. This man is simply one of the greatest soldiers to ever walk on planet earth.... Rest in peace Jochen and may someday the men who murdered you be tried and hung by the neck until death! Yours truly Derek an American

ReplyDeleteAgreed Derek.

DeleteToo bad some people admire psychopathic murderers.

DeleteI too am an American. I have read and watched everything available concerning Peiper, including traveling/walking his route from Blankenheim to Targnon. I also walked quite a bit of Kampfgruppe Peiper's escape route from La Gleize to Wanne. I stayed several nights at the Chateau Froidcour in Stoumont and spoke extensively with the grandson of the de Harennes, who lived in the chateau during the battle and served as a command post for Peiper as well as for the Americans. He stated his family was treated well by Peiper's troops. The Americans, who were there stole antiques and the silver. While there, I was reading Janice Holt Giles' book THE DAMMED ENGINEERS, which belonged to the de Harennes, and found a letter written by an American medic (Everette Smith) to the de Harennes. He took care of both German and American wounded during the battle. He wrote about his conversations with Peiper concerning the wounded and POWs.Very poignant! In the bedroom, in which we stayed, there were preserved notes written by the American POWs kept there. It was amazing an I learned a lot.

ReplyDeleteFor me, Jochen Peiper is one of the most fascinating, enigmatic, brilliant, tenacious, resilient, mentally and physically tough and admirable characters whom I've ever encountered. He is also witty and his letters are beautiful. Yes, he could be brutal, and fought for a despicable regime, but I believe he was a man of his times and circumstances. (The 2 pics of the Ardennes campaign, are most definitely not Peiper)

You really have no idea what, or of whom you are you are talking about do you?! This really is just trash. I have studied him for many years now and I am always surprised at how little people [like you] know about him.

DeleteI am finding that comment far off from the beginning of your article to be honest." Joachim Peiper, Ruthless Waffen SS Leader

ReplyDeleteWar Criminal Joachim Peiper Led His Troops To Death" -the very begining is actually the point of matter, as whole the rest follows that statement more or less. I think you have started it with open unsymapthy /hate and during the research you obviously did on his account , article seems to get milder somehow. I also find a statement "article, which is not meant to be comprehensive" wrong from the beginning. What would be a purpose and sense to write an article , which wouldn't give it's justice to that particular subject? Your article is not the shortest one to find about Peiper, so I assume you got your time to research about him and historical background properly. Or maybe you wrote that basing on one side's account? Why haven't you meant in your article, that it was a revision of "Nuremberg Malmedy trial" , because of many incorrections found in it? Instead of it you wrote , that the public attention was rather pointed on some big names as Göring, etc.

Why that?