|

| Adolf Hitler giving a speech. |

One of the strangest stories of World War II is the existence of peace talks during the conflict. These are almost never mentioned by modern histories, and there is every appearance of the powers that be trying their best to scrub them from history. There's some question as to whether they existed at all. However, the evidence suggests that they did, but nobody wanted the public to learn about them.

What's even stranger is that some apparently were initiated by the Third Reich.

Some of these peace talks are fairly well known. However, any attempt at peace by the Germans is completely discounted by just about everybody as simply a Hitler trick or propaganda. For instance, Hitler made several speeches in the fall of 1939, after he had conquered Poland, containing very broad suggestions that everybody should just "let it go" and allow him to keep his conquests. These were immediately brushed off by the British and French governments, so they can't really be considered any kind of peace "discussion." Hitler would have been delighted to have been forgiven immediately for his invasion of Poland, but that wasn't something the Allies were prepared to even consider.

On the other hand, there also were some attempts at peace by the Allies that have been kept very low-key, both at the time and in historical studies. They generally are considered either unrealistic or just an attempt to trick Hitler in return. There appears to have been some substance to some of the discussions, especially the later ones, so let's go through them.

Goering Has a Go

After weeks of preparation, on 7 August 1939 Hermann Goering participated in a secret meeting with a random group of English industrialists in order to jump-start peace talks. The meeting was arranged by unofficial Swedish diplomat Birger Dahlerus and held at Dahlerus' wife's farmhouse in northern Germany. It was the earliest peace feeler of the conflict, and in fact, preceded the first battle.

The meeting, despite its elaborate preparation and clandestine nature, had no discernible purpose, but it is notable nonetheless. It was set up casually by Dahlerus, to whom the idea came spontaneously after visiting England himself and then running into some of his new English industrialist friends back in Germany. Dahlerus himself knew Goering through his boss, Swedish Electrolux tycoon Axel Wenner-Gren, who had met Goering years earlier through the family of Goering's first wife Carin von Rosen. While Wenner-Gren himself liked to dabble in diplomacy, he wisely left the heavy lifting to his flunky Dahlerus to keep his hands clean.

The highly unusual meeting was held at Sönke-Nissen-Koog, Germany, a remote location on the western shore near the Danish border. At the meeting were:

- Brian Moutain

- Sir Robert Renwick

- Charles MacLaren

- T. Mensforth

- A. Holden

- Stanley Rawson

- Charles Spencer

Goering lectured the British men on, among other things, Germany's growing ability to synthesize gasoline from coal. He made extravagant claims as to how much could be produced that way within a few years. This foreshadowed a major war aim of the Reich, to assure its oil supplies which Hitler considered to be vulnerable to RAF attack in Romania and which were insufficient for its expansionary needs. The discussion was pleasant but also vaguely threatening. After several hours, Goering ended the meeting by proposing a toast to peace. Not a trained diplomat, Goering did not appear to have a set agenda for the affair. He was "winging it" and apparently felt it was enough to be friendly and bombastic that this alone would create an atmosphere conducive to further negotiations. It didn't.

Goering also was known to feel that Foreign Minister Ribbentrop was incompetent and a war-monger. In fact, Goering had tried before to bypass Ribbentrop, such as with Franco a year earlier (and been humiliated in the process). The stakes were growing higher all the time, so it was worth a try. Ribbentrop was creating in Hitler a false impression that the British would not fight despite massive provocation. As a former ambassador to the Court of St. James, Ribbentrop fancied himself something of an expert on the British mind, but in fact, he completely misunderstood the British character.

Goering wanted to score points with Hitler and undercut Ribbentrop by neutralizing England because he, in fact, did have a better understanding of the British and had no illusions of them standing idly by forever. Besides helping the political situation, it would help Goering personally. He had been disappointed not to have been appointed Foreign Minister himself, and still longed after the position (in addition, of course, to all his other roles). Such accumulation of titles by the bigwigs was a hallmark of the regime. This 7 August 1939 meeting was another step in that campaign.

Goering reputedly did not inform Hitler of the meeting with the industrialists, which took place during Goering's vacation. This was likely out of fear that Hitler would forbid him outright from making any peace gestures. Talking to the British also perhaps would reinforce Hitler's feeling that Goering was becoming timid (Hitler had taken to calling Goering "the old woman" behind his back due to Goering's caution about previous invasions). It is worth noting in this regard that when Goering openly broached the idea of himself going to London later that month, Hitler was adamant that it would be pointless and that Goering should not go.

However, Hitler did not want a general war either if he could help it - he just wanted to chip off pieces of other countries slowly, like a sculpture. He himself made some awkward peace attempts in 1940. It is perfectly reasonable to conclude that Hitler did know of Goering's attempt at negotiation but wanted his name left out of it, and figured later that Goering had tried and failed (which was true) so there was no point trying again.

Spencer later gave a full report on the meeting to the Foreign Office which accurately predicted the meeting which Hitler would hold at Berchtesgaden on 14 August to plan Case Yellow, the invasion of Poland. Thus, the event did have some small use to British intelligence, though it is unclear whether that affected policy. Goering appeared to be expecting some British response to his gesture, but nobody in England really knew what the question posed had been - if any. The British thus made no response and nothing came of the abortive peace feelers. Goering henceforth relied on Dahlerus for his unofficial diplomatic meddling, which continued well into the war but continually went nowhere due to Hitler holding all the reins of true power.

|

Hitler and Mussolini Have a Go

Hitler certainly invaded Poland, and that began World War II. Tens of millions of people perished as a result.However, Hitler never intended to begin a general war if he could help it. His major aim was just to recover the Polish corridor and Danzig. Beyond that, everything was negotiable.

On 19 September 1939, Hitler entered Danzig and gave a major speech. Among other things, he defended his alliance with the Soviet Union. He also made various belligerent claims about retaining Danzig forever and never surrendering (which was an oddly pessimistic viewpoint right from the start of the war).

Of more interest to us here is that he also suggested that the war could be ended with the status quo (dismemberment of Poland) intact. Hitler never came right out and said "send us peace negotiators." That he would have seen as weak. However, in his usual almost casual way that he affected at such moments, such as again in July 1940, Hitler did at least raise the issue of beginning some kind of dialogue.

|

| Mussolini orating. |

That this was not accidental, but in fact, very planned out, is seen from the fact that Mussolini expanded on this hint a few days later. On 23 September 1939, Mussolini gave a speech to fellow fascists in Rome. He urged a cease-fire and a peace based on current frontiers. He also somewhat ominously stated that Italy must "strengthen our army in preparation for any eventualities." He did, however, reiterate Italy's neutrality.

With both fascist dictators on board, there certainly was an opening for negotiations. However, both the British and the French responded by saying that peace with any government led by Adolf Hitler was out of the question. He could not be trusted and would violate any agreements whenever it suited him. Winston Churchill gave a speech on 1 October 1939 in which he summed up the first month of the war and not only never once hinted at any possibility at peace, but made conciliatory remarks to the Soviet Union. He said that while it was "riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma," it had to occupy Poland to protect itself from Hitler. The French Premier gave an emotional speech rejecting any idea of peace with Hitler, minus the charitable slant on Stalin.

Hitler did not give up so easily. In a major speech to the Reichstag on 6 October 1939, Hitler described his desire for peace with Britain and France. Hitler claimed that he had done nothing more than correct the unjust Versailles Treaty and that he had no war aims against France or Britain. He called out people opposing the idea of peace such as Churchill as "warmongers." He called for a European conference to meet and craft a solution. The French rejected the renewed proposal on 10 October 1939, and the British on 12 October 1939.

One must remember that when Hitler was making this 6 October 1939 speech, he already had, on 27 October 1939, decided to invade France. So, how genuine these offers were is, shall we say, extremely debatable. These could have been made to weaken the resolve of an enemy populace hungry for peace.

Lord Halifax Arranges Secret Peace Talks

There was a large body of opinion in England in 1939/1940 that it was not worthwhile to go to war over Poland despite any military guarantees given to it. Prime Minister Chamberlain had given away Czechoslovakia at Munich, and the world hadn't ended. In fact, the world was still tired from World War I and many were in no mood for another war if it could be avoided.British files declassified fifty years after World War II show that Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax sent one John Lonsdale Bryans, an old Etonian classmate, to Germany shortly after the outbreak of the war to see what he could do about stopping the fighting. Bryans first tried to contact opposition leaders in Switzerland to arrange a coup and thus an end to the war, but that failed. Then, he tried to arrange a meeting with Hitler himself.

The files show that the passport office issued Bryans a passport in January 1940 as follows:

"The permit granted on the 8th was given at the request of Mr CGS Stevenson, the Private Secretary to Lord Halifax, who telephoned to say that the Secretary of State wished that all possible facilities should be granted to Mr Bryans."Bryans, according to other documents, met with Halifax on August 25, 1939 - right after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact made Germany a huge threat to Poland and other surrounding nations. Bryans suggested that he would travel to Europe to make contact with groups opposed to Hitler, depose Hitler, and prevent any war from breaking out. From a document dated October 19, 1945:

"Lonsdale Bryans met Lord Halifax on 25 August 1939. That he should travel to Europe to make contact with enemy groups opposed to Hitler. Lord Halifax is reputed to have said that Britain would not fight for Danzig and the [Polish] corridor and later to have minuted that he was impressed by the proposal."Attempting to contact the enemy during wartime was a crime under the Defence Regulations (DR4A). While this first meeting was pre-war, the two countries were at war within a week, but as seen, Halifax continued aiding the secret endeavor. Bryans ultimately traveled by Portuguese vessel to Lisbon in December 1940, the usual entryway to Continental Europe by Englishmen during the war. That is, he was traveling after the fall of France and the Battle of Britain, at a time when Hitler had turned his attention toward Russia and would have loved to have had peace with England. Rudolf Hess' peace mission flight was only a few months later. Apparently, there were people on both sides who wanted out of the war.

What Bryans actually did in Europe remains a bit of a mystery. It also is a mystery how far Foreign Secretary Halifax was involved. Halifax was noted in early 1940 for being in the "listen to all peace offers" camp, which may have been one reason he was not chosen to replace Chamberlain as Prime Minister upon the invasion of France. Perhaps Bryans was acting on his own in trying to broker a deal with Hitler - but from the sound of it, Halifax was in it up to his neck and would not have minded a reasonable peace offer from Hitler before things got too nasty.

The X Report

There was a German opposition group throughout the war - in fact, it originated well before the start of hostilities. While its members changed over time, it was always trying to steer Germany away from (further) conflict. Who was in it and what happened them is an interesting and involved story that we will go into elsewhere. Here, let's keep it simple and straightforward and just name the key players in this particular incident.A window of opportunity to broker a deal directly with the British existed in the war's first few months. One of the resistance members, former Ambassador to the Vatican Ulrich von Hassell, was considered a great expert on foreign relations (probably more competent than von Ribbentrop and the other people employed by Hitler). Early in 1940, von Hassell drafted a "to do" list of things to do in a post-Hitler Germany. In essence, the document called for the elimination of Party rule and restoration of the rule of law.

Pre-war diplomacy was so strained that many negotiations proceeded through entirely private means. Von Hassell had a (future) son-in-law, one Detalmo Pirzio Biroli, who was acquainted with Englishman J. Lonsdale Bryans. Bryans was a high society figure who considered himself an expert on Germany, and he also knew Lord Halifax. He set up a back channel between the German opposition and the British government.

Bryan visited Halifax on 8 January 1940. He carried with him a personal message from Von Hassell which he had obtained from Biroli (Italy not yet being at war with England). Halifax was intrigued and sent Bryan back to Rome to set things up. It was all unofficial stuff - "The Foreign Office will deny anything at all happened" kind of thing - but Bryan visited with Von Hassell in Arosa, Italy on 22/23 February 1940. They reached an understanding which of course would have to be agreed to officially at some point. For the time being, they were just two guys talking.

The basic outline of the agreement was that Hitler would be deposed in some fashion, and Great Britain would enter into peace negotiations with a new German government without further ado. The exact agreement is not available, but reportedly it included:

- The British would accept and ratify the Anschluss between Germany and Austria;

- The Sudetenland would remain German;

- The independent Czech Republic would be reinstated, though not apparently one identical to its previous state, but smaller;

- The German-Polish border would revert to roughly that of 1914;

- Reduction of armaments by all parties and various social reforms.

Bryan took the draft agreement to Whitehall by 28 February, handing it to Alexander Cadogan. Cadogan, who basically ran the office for Halifax, found the whole affair extremely tedious (as he set forth in his diary), based as it was upon a highly unlikely contingency (the overthrow of Hitler). However, Cadogan duly passed the document along to Halifax. However, Halifax demurred, claiming that he was involved in another channel altogether. Basically, this channel merged with the one discussed below. These further negotiations, the "Vatican Exchanges," produced the X Report, which apparently greatly resembled the Bryan document.

The Vatican Exchanges

The German resistance group also had employed a Munich lawyer, Dr. Josef Muller, to approach the British concurrent with the Bryan initiative. Muller also happened to have close personal contacts of value, his being with the Vatican; he had met the (then future) Pope 20 years earlier and had various other friends at the Vatican. He began talking with his contacts as early as September 1939, and his friend the Pope agreed to act as an intermediary, a sort of "clearinghouse" of peace talks. Everything, of course, was completely unofficial, as Hitler would have immediately shot anyone involved. Almost nothing was committed to writing for this reason.Muller visited Rome in late February 1940, and afterward dictated to his wife, Christine, a report which summarized the state of the "negotiations." This is the so-called "X Report," which takes its name from the fact that Muller's name was replaced by "Mr. X" throughout to retain his anonymity.

Muller gave the X Report to German General Thomas, who handed it to General Halder. Halder, with some misgivings, then gave it to von Brauchistch on 4 April 1940. Now, Halder had contacts with the opposition, but von Brauchistch had none. After reading it, von Brauchistch refused to even discuss it, saying in so many words that even to look at it constituted an act of treason. He did not, though, turn in Halder, though he did ask that Thomas be arrested. Halder demurred and said that the right person to arrest was him, and von Brauchistch dropped the matter.

The matter ended there. The Germans invaded Scandinavia a few days later, on 9 April 1940, and that would have ended matters anyway. Since the whole thing depended upon the deposition of Hitler, which wasn't happening, it was all a waste of time - as Cadogan believed.

The X Report itself was kept in a safe in Zossen (Wehrmacht Headquarters south of Berlin) until 22 September 1944, when the Gestapo found it. The Report was burned along with other documents before the fall of Berlin. Muller wound up in a concentration camp as a result. The British, though, did retain some references to the X Report in Foreign Office Papers, so the whole affair is not simply a fantasy.

The account of the abortive X Report negotiations carried on through the Vatican is important because it shows that peace was still possible even after the invasion of Poland. Events were moving too fast, though, for these sorts of back-channel dealings to go anywhere. The Vatican Exchanges were conducted in good faith and for proper purposes, but they relied upon too many contingencies that proved impossible to arrange, primarily a successful insurrection against Hitler.

Hitler's "Last Appeal to Reason"

|

| Leaflets dropped by the Luftwaffe on London during 1940. |

By mid-1940, Adolf Hitler was master of the Continent. The British army had escaped at Dunkirk, but they had lost their weapons and no longer constituted a serious threat to his conquests. Hitler hadn't declared war on Great Britain until after they declared war on him, and some biographers claim he had nothing against the British at all. There even is an extreme body of thought that Hitler intentionally allowed the British escape at Dunkirk, though that is far-fetched. What seems clear, and as detailed at length in his book "Mein Kampf," is that Hitler's thoughts always lay to the East, not to the West, and he never made a serious attempt to invade England.

|

| As shown by this 1936 Daily Mirror "exclusive," Hitler had tried the "Appeal to reason" tactic previously. |

Accordingly, he decided to wind up the Western Front after conquering France. On July 19, 1940, in his famous "Appeal to Reason" speech, he said that "there is no reason this war must go on." Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels made sure the speech received worldwide airing, and German bombers dropped leaflets about the offer on London throughout the Battle of Britain.

There is every indication Hitler really did want to call the whole war against England off. He waited around in one of his western bunker headquarters waiting for a reply to his terms, then seemed to lose interest in England altogether. Ultimately, he and Hermann Goering turned their backs on England and focused on Hitler's real objective: the Soviet Union. However, they really did not want to fight England to a decision.

Lord Lothian, the British ambassador to Washington, actually asked the German ambassador (through a Quaker intermediary) for Germany's terms in July 1940. When Churchill heard about this, he was furious and forbade any further such inquiries. During the war, any such exchange was viewed as a sign of weakness. Churchill was an adamant hawk who had no intention of opening any sort of talks with Germany.

A few steps were taken to force Churchill to talk. German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop made a half-hearted attempt to capture the Duke of Windsor while he was waiting near Lisbon for transport to the Bahamas in July 1940. The Duke and Duchess had met Hitler before the war and made some statements that could be interpreted as pro-Hitler. It is believed that Ribbentrop planned to use the Duke to start some kind of negotiation with Churchill or perhaps use him as a bargaining chip. However, the plan to kidnap the Duke fell through, and he sailed off to the Bahamas - where he was under suspicion of sympathies to Hitler throughout the war and was closely watched.

|

| Lord Halifax. |

Italy secretly wanted out of the war, and it continued to look for ways from 1940 onward.

Italy-Great Britain Talks Via the Vatican

The Vatican continued to interest the Allies in peace talks virtually throughout the war. The problem is, the two sides were never really serious about it at the same time. There were some momentary flashes of interest here and there by the Allies, but nothing solid. None of these talks appear to have been entered into in good faith by both sides at the same time. |

| Italian troops invading British Somaliland in August 1940, a long-forgotten campaign. |

One of these transient opportunities occurred when Italy invaded British Somaliland early in August 1940. The possibility of mediating some backdoor talks between Italy and Great Britain was floated by the Vatican. Nothing ever came of it, despite some apparent low-level discussions. That incident did have one possible real-world effect: some say that the Italians went easy on the British as they were withdrawing from Berbera to Aden across the Gulf of Aden in mid-August (similar to what some say about Hitler and Dunkirk) in order not to disturb these supposed peace talks.

One can easily see the British dangling a promise of peace before Italy in order to ease that evacuation, then snatching it away when the troops were safe. Contemporary accounts note that the Italians did not bomb the evacuation transports as much as they easily could have for this reason, and also did not attack Berbera as hard as they could have while the British were still evacuating. Others will respond that the Italians, in fact, did attack throughout that campaign, even if their attacks were typically weak Italian efforts. This kind of thing happens all the time - posing the possibility of a larger deal in bad faith to stay the hand of an aggressor during a momentary period of vulnerability - so it is quite believable. However, the proof is lacking.

Soviet Overtures to Germany Via Bulgaria in June 1941

Immediately after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa, Stalin and Molotov directed Lavrentiy Beria to arrange peace talks with Germany. This was done through NKVD officer Pavel Sudoplatov, who met with a Bulgarian diplomat in Moscow, Ivan Stamenov. The understanding was that this Bulgarian diplomat would communicate with Adolf Hitler with details of a peace proposal directly from Stalin. This was during Stalin's "missing week" immediately following the invasion when he did not communicate with the public and is assumed to have had some kind of personal crisis. |

| Lieut. Gen. Pavel A. Sudoplatov. He headed Stalin's failed attempt to broker a peace deal with Hitler shortly after the German invasion of the Soviet Union (Image: novayagazeta.ru). |

These peace talks obviously went nowhere because Hitler was not interested. They were kept in extreme secrecy until Beria revealed them under interrogation following his downfall in June 1953. Sudoplatov also confessed to these activities, while the Bulgarian involved, Stamenov, provided a letter of confirmation of the whole incident. A special session of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union headed by Marshal Ivan Konev found Beria guilty of Treason for this and also convicted him on other charges. Beria was immediately executed by General Pavel Batitsky.

Soviet 1941 Proposal to Finland

|

| Ambassador Hjalmar Procope. |

On 18 August 1941, the Soviet Union uses US Secretary of State Sumner Welles as an intermediary to discuss peace terms with Finland. The Soviet proposal is to modify the Peace of Moscow of 1940, which ended the Winter War, to grant Finland some concessions. Finnish Ambassador Hjalmar Procope replies to Welles that the future of Finland depends upon what happens to the Soviet Union after the war, and requests a guarantee to Finland from the Western powers that they will protect Finland if Germany loses the war (which nobody expects at this point). Welles refuses to even consider such a guarantee. The peace feelers go no further.

Kirovograd Peace Talks

The Kirovograd conference - assuming it existed - is perhaps the murkiest incident from the entire war. The sources are so scant that any discussion of it necessarily requires a look at the sources. Unfortunately, they, too have their problems. However, there is just enough evidence to lead to the conclusion that the Kirovograd peace talks did happen, but they failed.First, the knee-jerk reaction is to assume that because there is so little known about this supposed event, that is proof that it did not happen because otherwise, the incident would have found its way into various memoirs and other works. However, these talks obviously were highly sensitive and would have been kept top secret, if only for each side to keep open the chance to re-open the talks later in the war if necessary. After the war, it was really in nobody's interest to talk about them.

The principal on the German side - German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop - was hanged at Nuremberg and had no chance to write about the event. The Soviet representatives at Nuremberg would have had a fit if he had brought it up, and he was fighting for his life. His silence means nothing.

|

| Ribbentrop, Molotov, and Stalin were all acquainted with each other. |

The Germans destroyed their documents at the end of the war, so the absence of proof there also means little. We are left with what various minions who were involved said afterward, and there it gets interesting.

The Soviets have all been silent, but that is completely understandable. If Molotov wasn't going to bring it up, lower-ranking apparatchniks certainly were not going to do it. By the time the Soviet Union collapsed around 1990, anyone involved on the Soviet side may have been dead or still scared of reprisals from hard-core Soviets.

It is on the German side, therefore, that we must look. The Germans had nothing to lose in disclosing any failed peace talks. It is there that we strike gold.

Peter Kleist was the head of the Eastern Department of the Dienststelle before the war. According to Michael Bloch in "Ribbentrop" (Crown Publishers 1992), Ribbentrop asked Kleist on April 7, 1939, to "improve his contacts" with the Soviets. Kleist followed through and visited the Soviet Embassy, and found to his astonishment that the Soviets were interested in doing a deal. This began a long sequence of events that culminated in the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact in August that led directly to World War II. So, Kleist was a key player, not a maid or a chauffeur or someone simply fantasizing.

In his memoirs, Peter Kleist wrote about the Kirovograd conference, and that appears to be the main source of support for it in the record.

Bloch continues on page 386:

Peter Kleist head of the Eastern European Department of the Dienststelle, was involved in 1943 in organizing the repatriation of the Swedish minorities in the Baltic States. During official visits to Stockholm for purpose, he made the acquaintance of Edgar Klauss, a Baltic German businessman of uncertain background who had contacts with the Soviet Legation. According to Kleist's memoirs, Klauss called upon him unexpectedly at his Stockholm hotel on 18 June 1943 with an offer to arrange a meeting with Alexandrov, a senior Soviet official Kleist knew from pre-Barbarossa days. Klauss explained that the Russians were disenchanted with the Western Allies and interested in exploring an arrangement with Germany on the basis of a return to the Soviet frontiers of 1939. Kleist returned to Berlin shortly afterwards, wondering how to present this proposal to Ribbentrop - only to find himself arrested on arrival and interrogated by the Gestapo. It transpired that the SD had found out about his conversation with Klauss and reported it to Hitler, who had angrily dismissed it as 'a Jewish provocation'.....

Hitler then turned his attention to the Kursk battle, which history records as a German failure. Ribbentrop then decided to re-examine the non-starter peace talks:

In mid-August Ribbentrop held a four-hour meeting with Kleist at Steinort, and afterwards asked Hitler's permission to send him back to Sweden to resume contact with Klauss. Hitler agreed, but merely to see what further information Kleist could pick up, particularly on the question of inter-Allied disagreements; Kleist was not to meet any Russians or give the slightest hint that Germany would even consider the possibility of negotiations.

Kleist returned to Stockholm where he saw Klauss again on 4 and 8 September, to be told that the Russians were upset by the lack ofresponse in their June feeler. They were still interested in talks, but the military situation had changed and the basis of discussion would be different. The Russian frontiers to be restored would have to be those not of 1939 but of 1914; Germany would have to give Russia a free hand in the Straits and in Asia; and any negotiations would have to be preceded by a gesture indicating a change in German policy, in the form of Ribbentrop's departure as German Foreign Minister. At the second meeting, Klauss announced Dekanozov, the former Soviet Ambassador to Berlin and now Deputy Foreign Minister, would be in Stockholm from 12 to 16 September and had been authorized to talk to Kleist.

On 10 September Kleist was back in Germany and reported these conversations to Ribbentrop. In view of the Russian suggestion concerning Ribbentrop's replacement, it must have been a strained

interview. However two days earlier the Allies had landed in Calabria and the Italians defected from the Axis, developments which lent a new urgency to question of Russian talks. Ribbentrop therefore begged Hitler to authorize Kleist to meet Dekanozov. As he wrote in his memoirs:

"This time Hitler was not as obstinate as in the past. He walked over to a map and drew a line of demarcation on which, he said, he might compromise with the Russians. But when the next day came, nothing happened. The Fuhrer said he would have to consider this more thoroughly" . . .

A few days later Mussolini arrived at Hitler's headquarters following rescue from the Gran Sasso. To Ribbentrop's surprise. Hitler announced to the Duce

"that he wanted to settle with Russia. But when I thereupon asked for instructions I received no precise answer, and on the following day the Fuhrer once more refused permission for overtures to be made. He must have noticed how dejected I was, for later he visited me at my headquarters, and on leaving said suddenly: 'You know, Ribbentrop, if I settled with Russia today I would only come to blows with her again tomorrow - I just can't help it.'"

Though Dekanozov had come and gone, Hitler authorized a further exploratory visit by Kleist to Stockholm. It was clear that Hitler had interest in talks, however, and the Americans had now got to hear of the business; so Klauss had to tell Kleist on 28 September that the Russians had withdrawn their approaches for the time being.

Some mystery still surrounds this episode. Did Stalin genuinely wish to reach a compromise with Hitler? Or was he trying to frighten the Allies into launching a second front and conceding the future overlordship of Eastern Europe? It is significant that in September 1943, at precisely moment Klauss was trying to bring about the Kleist-Dekanozov meeting Stalin suspended the activities of the Tree Germany Committee' which he was grooming as a German government-in-exile in the Soviet Union. This suggests he was serious about talks. He is known to have been furious at the decision of Churchill and Roosevelt in May 1943 to postpone the invasion of North-Western Europe until 1944; he was doubtless tempted by the prospect of recovering lost territories by negotiation rather than long and bloody reconquest. By late September, however, it was clear Hitler was not interested in negotiations; Stalin then decided to reveal the Klauss-Kleist meetings (which he represented as a German initiative) to the Americans in order to give them a fright.So, there is some evidence. Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart, a top scholar on warfare and tactics, as well as noted author of World War II reference works such as "The German Generals Talk," also mentions the conference in his "History of the Second World War," where he wrote on page 510, "In June 1943, Molotov met Ribbentrop at Kirovograd, which was then within the German lines, for a discussion about the possibilities of ending the war..." Hart's description derives from an alleged conversation he had with an undisclosed German major who allegedly participated in the talks. There are few sources better on World War II than Hart.

There are other sources, not all just based on Kleist's memoir. Heinz Magenheimer, an Austrian military historian, describes the meeting in "Germany's Key Strategic Decisions 1940-1945." He claims that Molotov revealed the negotiations to the Western Allies in November 1943. Gerhard Weinberg in "A World At Arms" (1994) also mentions the talks.

Robert Payne, in "The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler" (Praeger 1973) goes into some detail about the talks at page 478. Unfortunately, Payne also wrote an entire chapter about Adolf Hitler supposedly visiting England, with all sorts of details, that nobody else knows about and apparently never happened. He claims that the talks took place in June 1943, right before Kursk, and foundered shortly thereafter because neither side was really interested in peace. Payne writes with a lyrical prose, but he seems a bit slippery at times with actual facts.

The sum total of all these disparate sources is that Kleist, a specialist in arranging talks with the Soviets, apparently arranged some in mid-1943 at Kirovograd, behind the German lines. Molotov showed up with his aides, just as he had in Berlin in November 1940. It must have seemed like old times, and my how things had changed. The two sides spent a few days talking, and the talks may or may not have continued into the fall, but the Soviets demanded a return to the old frontiers and some other concessions that Hitler had no intention of accepting. At some point, one side or the other (they both had the motivation to do so, for vastly different reasons) leaked word of the talks to the Western Allies, and that ended everything.

Something probably happened. Talks after Stalingrad would have made sense to the Germans, and the fact that the Germans were readying for another offensive and had already recovered ground earlier in 1943 would have motivated the Soviets. However, the details are all conjecture.

Coco Chanel 1943/1944

One of the touchier subjects of World War II from a high society standpoint is exactly what was going on with Coco Chanel. Even today, after all the documentation ever likely to be produced, is out, it remains murky.

Gabrielle Bonheur "Coco" Chanel was, of course, the top fashion designer in France before and after the war. Whether or not she actually was all that good as a designer is beside the point: she became a global brand, and whatever you might hear about her other skills, that takes a special talent all its own. One could say she was perhaps the top businesswoman of her time - and that is how she comes to our attention.

During the war, Coco dated Baron Hans Gunther von Dincklage, who was a professional Abwehr spy 13 years her junior. This enabled her to live in the fancy Hotel Ritz in Paris during the war, which was quite unusual for a Frenchwoman because that was where the top German Luftwaffe brass such as Field Marshal Sperrle also lived. The Germans, despite all their other faults, were respectful of social status even among some of their former enemies. Chanel, of course, also had her ways with men, especially lonely men.

There are official declassified documents from the French Defense Ministry suggesting that Coco - who was around 60 years old during the war - collaborated with the Germans and was an actual, true-to-life spy. She even had a spy code number and everything: F-7124. How cool is that?

Where it gets fuzzy is exactly what Coco supposedly did beyond some cut-throat business dealings. However, one incident stands out above the others.

The war obviously was going badly for the Germans by late 1943. Italy had changed sides, and the Soviets were blasting through the best German troops in Ukraine. However, the Germans still had many cards left to play, including retention of all of France, much of Italy and virtually all of Scandinavia and Poland. The British and Americans hadn't invaded France yet, but everyone knew it was only a matter of time.

At this point, the Germans decided to have Coco use her womanly wiles to get them out of the war in the West. Since she was so chummy with the brass at the Ritz, it must have been easy to set up, perhaps over cognacs late at night after a full meal.

Coco, perhaps realizing that she had to do something to merit her continued good fortune under the Germans, agreed to go talk to her good friend British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to end this silly war business. As we know, there were unofficial contacts between the British and Germans at various times during the war, though they always came to nothing. The war was not going to end merely because of a social visit, but the process had to start somewhere.

|

| Coco with Winston Churchill and his son Randolph, apparently on a hunting trip before the war. |

Coco, the story goes, accordingly flew to Lisbon, which was Spy Central during the 1940s. Portugal was neutral (as, technically, was Spain, though it pushed the boundary of neutrality), and Lisbon had direct flights to London and Paris. Going from the German to the British side of the front was a simple matter of changing planes in Lisbon as if the war had never existed. Of course, that makes it sound a lot more normal than it was - famous actor Leslie Howard of "Gone With the Wind" (apparently also a spy) was shot down by German fighters on such a routine passenger flight from London to Lisbon on 1 June 1943. However, if you wanted to go from one side to the other, it was a heck of a lot easier to do it via Lisbon Airport than the alternatives (as referenced in the classic film "Casablanca").

Apparently, after suitable diplomatic arrangements had been made, Coco would get on a plane and meet Churchill. However, this is where the plan collapsed. Coco insisted that her friend, an Italian lady with whom she supposedly was in love, carry Coco's letter to Churchill to set up the meeting. Inexplicably, the Italian lady lost her nerve at the last minute, and the whole thing never happened. The Germans must have had a good laugh about the fickle women trying to do man's work and act like diplomats.

After the war, Chanel was questioned but never convicted of any sort of improper activities. It is easy to throw around words like "traitor" and "collaborator," though, and the partisans were not in a an understanding mood for someone who had lived the life of luxury on the German dime while they suffered deprivation and, when caught, death. Coco wisely decided to seek friendlier climes after the Germans were booted out of France in late 1944. She fled to Switzerland with her German boyfriend, but eventually returned to Paris after things quieted down. Coco died in her sleep at the Ritz in 1971. Her brand lives on.

Hitler September 1944

This is a little-known episode from the war. The only place I have seen this mentioned in is in Earl F. Ziemke's 'Stalingrad to Berlin: The German Defeat in the East" (Barnes & Noble 1996).There are only a couple of oblique references to this. Ziemke gives as his source Alfred Jodl's War Diary ('Tagebuch") from 16 Sepember 1944.

|

| Colonel-General Alfred Jodl at the capitulation. |

This was the same time that Finland was pulling out of the war. Hitler thought very highly of the Finns, and their departure after over a year of mulling it over must have had an effect on him. The Finns were negotiating through the Soviet Ambassador to Sweden, Madame Alexandra Kollontay/Kollontai (later nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1946 and 1947).

|

| Madame Kollontay. |

Kollontay, incidentally, is a fascinating character. A friend of Lenin, she reputedly was the template for the Greta Garbo character in 'Ninotchka' (1939). Kollontay is mentioned occasionally in high-level German sources, which references are amusing to read because they invariably refer to Kollontay as a lesbian (they did not particularly like her negotiating with the Finns), which she apparently was not (though she was famous for unconventional ideas about love and marriage and, who knows, may have been a closeted lesbian anyway despite being married). Discussions about negotiating with her were treated by the Germans like a potential trip to the Dentist to have serious work done.

Some sheer speculation here: during those talks between Finland and the Soviets, which were prolonged over several years and which everyone realized were increasingly real as the war got further along, the Soviets may have dropped some hints that they would be willing to at least discuss a separate peace with Hitler. Kollontay, for instance, could have seen her growing progress with the Finns and said something along the lines of, "You are being quite reasonable, why don't you talk to Adolf and have him send somebody along that I can work with next time we meet, too?" However, we know nothing about those talks or any mention during them of Germany, and let me emphasize: it is sheer speculation. However, it is difficult to see where else any serious thought of peace talks with Stalin could have arisen at that point.

By that point, the vulnerability of Army Group North had become critical, and General Ferdinand Schoerner requested permission to withdraw. It was the prudent military course, and Schoerner was one of the Generals that Hitler knew was a fanatic and would not request a withdrawal unless it was absolutely critical. When faced with such a reasonable request, Hitler approved more often than is commonly realized (and also often made completely insane decisions to hold hopeless positions against all military logic).

|

| General Schoerner with Hitler toward the end of the war. |

Schoerner showed up at Hitler's East Prussian headquarters to get approval. Here is what Ziemke has to say about this (page 404):

Ultimately, Hitler did approve the withdrawal, probably only because it was Schoerner requesting it.As always, Hitler was reluctant to approve a retreat. With inverse logic, he argued that III SS Panzer Corps on the outer flank between Lake Peipus and the Gulf of Finland would not be able to get away in any event. He also claimed that the Soviet Union had peace feelers out, and he needed the Baltic territory to bargain with.

There is one more curious entry on the next page that is the only other reference to this incident:

That night (16 September) [General Heinz] Guderian told [General Georg-Hans Reinhardt] that because 'great things' were in progress in foreign policy (the alleged Soviet peace feelers?), Hitler "absolutely had to have a success either at Third Panzer Army or at Army Group North." The 'instant' that he could see that the attack was not going to succeed, Reinhardt was to report it to Hitler and and get ready to transfer the divisions to Army Group North.The parenthetical question is Ziemke's, who apparently found this to be curious, too.

These passages raise all sorts of questions that have no answer. The possibility that Hitler may have been fabricating the occasion of peace talks is always possible. However, this is a very rare incidence where Hitler mentioned anything like this.

More likely, Madame Kollontay said something off-hand to the Finns, who, knowing that they would face casualties from kicking the Germans off their territory as part of any peace deal of their own, gave Hitler some kind of indication that a peace deal was also possible to include Germany. Since there is no other reference to this particular talk of peace, it obviously went nowhere even though Hitler's troops did solve their short-term problems in the north.

This incident may help explain why Hitler was so adamant about keeping troops in the Courland pocket long after they ceased to have any use there. It cost many German troops their lives since they ultimately wound up in Soviet captivity, where the vast majority perished.

Rudolf Hess Flight to England 1941

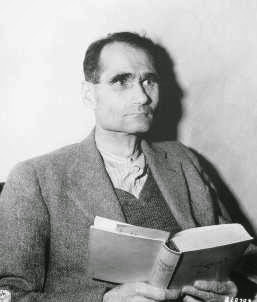

|

| Rudolf Hess in prison. |

Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess was one of the top men in Hitler's inner circle during the 1930s. He had transcribed Hitler's "Mein Kampf" while in prison with Hitler in the 1920s, and he was in very tight with the Fuhrer. By the early 1940s, however, Hess was rapidly losing ground to the likes of Martin Bormann and Hermann Goering. He was not one of the top leaders who enjoyed the trappings of success: he lived in a small, unadorned apartment and is not reported to have had mistresses or things of that nature. Instead, he apparently really believed in National Socialism and wanted it to succeed. He had little to give up, and no future in the regime except continued diminution of power.

In early 1941, all of the top German brass knew about Hitler's plans to invade the Soviet Union (Stalin apparently knew as well from sundry sources, and Churchill likely did, too, via Ultra). The Germans, however, traditionally feared a two-front war. Hess decided to take matters into his own hands and clear German's rear in anticipation of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Just before 6 pm on May 10, 1941, Hess took off from Augsburg Airfield in Bavaria in a Messerschmitt Bf-110. After a flight of 1000 miles (a one-way ride, the 110 had just enough range) during which he successfully eluded Spitfires sent up to intercept him, Hess got lost in the dark, ran out of fuel close to his objective, and parachuted out. Upon landing, Hess hurt his ankle and immediately was apprehended by a pitchfork-wielding Scottish farmer, David McLean.

McLean took the deputy fuhrer to his cottage, where Hess politely only accepted a glass of water. Soon, a convoy of cars arrived - somehow the British knew who Hess was despite calling himself Alfred Horn, and they had been waiting at a nearby airfield for him - and transported Hess to a hall in nearby Busby. Afterward, Hess moved to Maryhill Barracks in Glasgow and stayed at a military hospital there.

Having spent his night in a Scottish military hospital following his bizarre flight to Great Britain on the 10th, Rudolf Hess sleeps late and then is ready to discuss - something. British intelligence service spy Ivone Kirkpatrick flies up to visit Hess, who seems a bit confused about who he is actually dealing with. Hess tells Kirkpatrick that he has come to talk peace and spells out his proposal, and it is all taken down by a stenographer. Kirkpatrick was somewhat bemused by Hess' attitude, which was that of a victor making a generous offer. Whether Hess actually was communicating an offer from Hitler is debatable, although Hess was adamant that he was an unofficial emissary.

Hess claimed he had come to offer peace terms. The "Hess Peace Plan," if it can be called that, is murky. Apparently, in essence, Hess offers an armistice wherein the Germans will evacuate all of France except for its traditional territories of Alsace and Lorraine. In addition, Germany would relinquish Holland, Belgium, Norway, and Denmark, while keeping Luxembourg. Furthermore, Germany under the right circumstances would agree to give up Yugoslavia and Greece and, apparently, North Africa. Everything depended upon neutrality by Great Britain that was "benevolent," which suggested tacit support for further Reich adventurism.

It is unclear how specific Hess was about Hitler's plans in the East, but there seems little question that at the very least he dropped very broad hints that the Soviet Union was Hitler's real military objective. Hess was very clear that Hitler wanted peace in the West and would make massive concessions to achieve it so that the Reich could have peace. There was a sense that Hess (and presumably Hitler) wanted to turn the entire war into a crusade against Soviet communism, something that the Japanese also were hinting at in their secret negotiations with the Americans on this very day. Kirkpatrick nodded and took notes throughout the day, as Hess proves to be quite talkative, but Kirkpatrick was not a dealmaker and was simply there to get information.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, staying at his country home at Ditchley near Oxford, was not interested enough in Hess to even interrupt a special screening of the latest Marx Brothers film. However, he did ask the Duke of Hamilton to report in person. After Kirkpatrick reported back to Churchill on the 12th, the decision was made that, whatever the Hess terms were, they were completely unacceptable. The British and Americans rejected them out of hand. One mystery is why Hess thought they might be acceptable when the British had flatly rejected Hitler's own peace proposal the preceding year.

After learning the terms of the proposal, Churchill cabled President Roosevelt. They both agree that disseminating the proposal would be hurtful to the war effort and must be kept secret. Hess was moved to the Tower of London where he became the last political prisoner to be held there. He then was moved to Mytchett House near Aldershot and various other locations until he was incarcerated for life in Spandau Prison. Asked about Hess during the Nuremberg trials, Churchill peremptorily dismissed trying him, saying that the Hess situation was a medical issue and nothing more need be done about him. That is how it remained until Rudolf Hess' death at Spandau in the 1980s by suicide.

|

| Hess and Hitler were huge buddies from the Putsch days. |

The German reaction was almost as interesting as that of the British and Americans. Hess' adjutant who had accompanied him to the airfield, Karlheinz Pintsch, acted upon Hess' final instructions and carried Hess' special letter addressed to Hitler to the Berghof, where the Fuehrer was enjoying a working holiday. Accounts differ on exactly how Hitler responded, and the generally accepted view is that Hitler was shocked and immediately ordered German state media to disavow Hess and claim that he had gone mad. This is the standard textbook line.

However, according to Pintsch's own account written in February 1948 (discovered in the 21st Century in the State Archive of the Russian Federation by German historian Matthias Uhl of the German Historical Institute Moscow), Hitler was not surprised at all when he read the letter. In this account, Pintsch wrote, "Hitler calmly listened to my report and dismissed me without comment." Pintsch also wrote that the flight had been arranged in advance by Hitler with the British, a view supported by the presence at the Duke of Hamilton's airfield of secret service agents awaiting Hess. Why would they have been expecting Hess if the visit hadn't been arranged through diplomatic channels of some sort? Churchill also did not seem altogether startled by Hess' arrival, judging by his immediate reaction.

Hitler's butler, Heinz Linge, stated (also after the war) that Hitler's "behavior told me that not only did he know about [the flight] in advance, but that [Hitler] probably even sent Hess to England." This interpretation of Hitler's reaction was echoed by two others at the Obersalzberg that day, Ernst Wilhelm Bohle, the head of the Nazi Party's foreign organization, and Hermann Göring's liaison Karl Heinrich Bodenschatz.

Hitler did order Berlin radio to put out a cover story that Hess was insane, something that Hess himself suggested in his letter to the Fuehrer. That remained the official German foreign stance thereafter. But what was really going on may have been quite different.

.JPG) |

| Troops guarding Rudolf Hess at Spandau in 1983. |

It is highly unlikely that Hess was, in fact, crazy. He just was unsuccessful at his hopeless peace mission. Calling Hess crazy was the easiest way for the Allies to avoid hanging him, and who wants to hang a man who came across the lines willingly on a peace mission, however misguided? The funny thing is that everyone seems to just accept the story put out by Hitler that Hess was crazy. There is no proof such was the case, and Speer in his memoirs "Spandau: The Secret Diaries," after having spent twenty years living with him, gives little indication that Hess had lost his mind.

One thing the "insane" flight ultimately did was to save Hess' life. Churchill intervened directly to prevent Hess' execution after conviction at Nuremberg because he was a "medical case." It also led to the rise of Martin Bormann within the Reich hierarchy, since Hitler appointed Bormann to replace Hess a few days later. Bormann, of course, also disappeared at the end of the war. There's just something odd about almost every aspect of this affair.

Rudolf Hess spent the rest of his life in Spandau prison, alone for the last 20 years. He was judged insane and thus not subject to execution. According to Albert Speer in a post-release interview, Hess was quite happy in Spandau, having finally become the undisputed top deputy to the Fuhrer, at least until the futility of his life finally got to him and he committed suicide in the 1980s. Whenever asked any pointed questions, Speer would just smile.

What is uncanny is that Hess' desire to broker a peace deal with Great Britain prior to Operation Barbarossa and get Germany out of the war somehow was perhaps the single smartest thing ever attempted within the regime.

Heinrich Himmler's Secret Deals

That SS boss Heinrich Himmler was trying to work something out with the Allies during the Reich's very last days in April 1945 is well known. He dickered with the Swiss about trading trainloads of Jews who were otherwise destined for the concentration camps in exchange for nebulous concessions that would protect his own position in a post-war Germany. The attempted deals pretty much went nowhere, and Adolf Hitler only learned about them at about the point in time when he was raising the gun to his own head. At that point, only a madman such as Hitler would have been against peace talks.

What isn't as well known is that Himmler had been cautiously looking to make a deal for over a year at that time. By early 1944, the writing was on the wall, with the Germans being pushed back steadily in Ukraine to pre-war Polish territory. Invasion of France by the Allies was a foregone conclusion, the only questions were when and on what beaches. The only thing standing in the way of a peace deal was Hitler, so Himmler tried to go around him.

In March 1944, in order to assert complete control over one of his dwindling number of allies, Hitler had sent his troops to invade Hungary ("Operation Margarethe"). While of no effect on the overall military situation, this invasion had a very big effect on the country's large Jewish population. Hitler had been able to give Himmler a free hand to exterminate the Jews and other undesirables within Greater Germany and the occupied areas of Europe such as Poland and the western Soviet Union, but he had been stymied within the territory of his allies by those countries' leaders (Admiral Horthy, Mussolini, Mannerheim etc.) who did not share Hitler's viral brand of anti-Semitism. That obstacle disappeared when Hitler actually invaded, as he did in northern Italy, unoccupied France and Hungary.

So, the Hungarian Jews now were at great risk. The Germans didn't waste time: once they had their men in place, they started compiling lists of Hungarians with whom to load the trains to Auschwitz.

|

| Adolf Eichmann in 1940. |

Himmler apparently (he never showed his cards directly, that was not his style, he sent underlings to do that) saw an opportunity in this new situation. He sent Adolf Eichmann down to Budapest to talk to the local Jewish rescue group (the "Aid and Rescue Committee"). Eichmann contacted one of their number, one Joel Brand, to do a deal: Himmler's SS (technically, the German Sicherheitsdienst, but Himmler controlled the entire apparatus) would release a million Jews to the west in exchange for 10,000 trucks and large quantities of consumer items that were in short supply in occupied Europe, such as tea. The apparent conclusion to be drawn was that the SS wanted to start talks that would lead much further.

|

| Joel Brand in 1961. |

Brand wound up going to Istanbul, Turkey in May 1944 to try and work out a deal with the Americans or maybe the British, but the British were in no mood to talk about anything with the Germans. They quickly kidnapped Brand as soon as he arrived in Istanbul and held him for questioning. Ultimately, the British flatly rejected the very idea of any such deal and sent Brand on his way down to Palestine. The larger situation then rapidly changed, as the Germans were not going to wait around with trainloads of Jews ready to go as the military situation started crumbling around them. They started the trains in motion, and hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were sent to the camps and perished.

What's most interesting about this proposed deal is that it was quite similar to what Himmler tried to do a year later, which was another attempt to open peace talks using Jews as bargaining chips. With Hitler a roadblock to any negotiations, Himmler tried to go around Hitler through his own devious means. It didn't work and stood no chance of working, but it was an odd attempted deal in the midst of mass murder.

2014

No comments:

Post a Comment