The Bombing of the US Mainland in World War II

|

| Brookings, Oregon coastline |

There are many tales of German plans to bomb the United States. The accounts dribbled out after the war, with this old Luftwaffe pilot or that recalling how an "

Amerika bomber" came within sight of Manhattan or was slated to bomb the Detroit aircraft factories, or maybe even crashed just off the coast of Maine. There is no solid evidence anything like that ever happened, and it is highly likely that no Luftwaffe bomber ever approached American territory during the war, much less bombed it. But that doesn't mean that the Axis powers never achieved this fantastic goal.

In fact, they did.

|

| The true Amerika Bomber. |

People interested in the subject looked in the wrong direction the entire time. On 9 September 1942, though, something happened that had never happened before:

an enemy plane bombed the United States.

There had been rumors of bombers over Los Angeles the previous December, but those were ultimately proven false. And, of course, U.S. territory in one form or another was bombed in Guam, Hawaii, Alaska and a few other areas in the Pacific - but those were not States at the time. It would be as if something happened today in Puerto Rico - sure, American, but not actually a State of the Union.

However, one man actually did it - he flew his plane over the lower 48, dropped his bombs on target, and returned safely home. Mission accomplished. Twice.

That man was Nobuo Fujita.

|

| Nobuo Fujita - an enemy during World War II, but a class act afterward |

Japanese submarine I-25, with a crew of about 100, surfaced before dawn on 9 September 1942 just off the coast of Oregon after crossing the ocean outside of normal shipping lanes. The location was not chosen by chance: the I-25 was quite familiar with the area. In December 1941, it had attacked two oil tankers at the nearby mouth of the Columbia River protected by Fort Stevens. Not spotting the sub, the fort's guns remained silent, perhaps out of fear of giving away their location to no purpose. The I-25 damaged the empty oil tanker S.S. Connecticut by torpedoing it with one of its 17 torpedoes, then slunk away.

|

| Fort Stevens during World War II |

So, altogether not impressed by the Americans' failure to respond to the torpedo attacks, I-25 returned the following summer. On the night of June 21, 1942, the I-25, under the command of Commander Tagami, opened fire on Fort Stevens with its 5.5 deck gun after maneuvering around minefields it knew about from the previous attack.

|

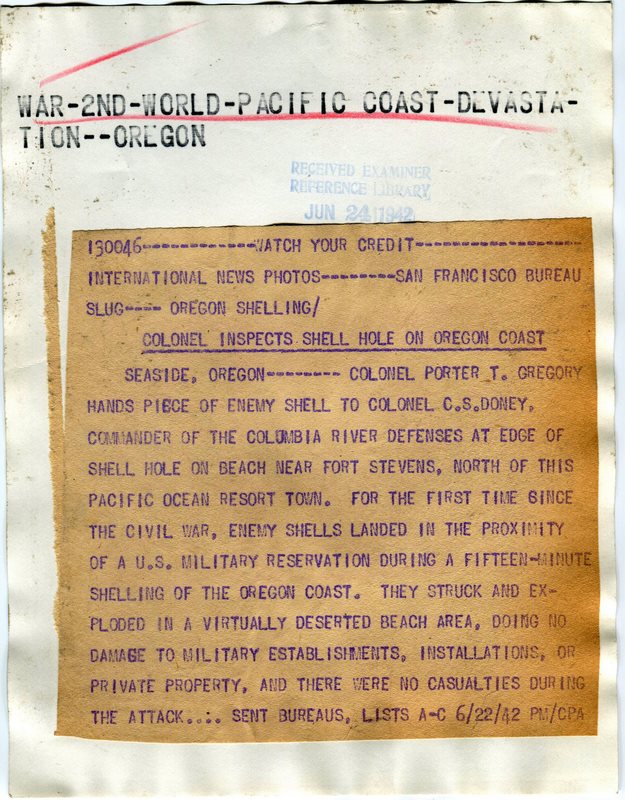

| The news dispatch. |

Seventeen shells landed on the military reservation without causing significant damage, and once more the fort’s guns under Major Huston remained silent—among other reasons, the submarine was believed to be out of range. I-25 thus already had a distinction: Fort Stevens became the only military installation in the contiguous United States to be shelled by a foreign enemy warship since the War of 1812.

|

| A shell crater on US soil put there by the Japanese. |

A stone monument south of Battery Russell commemorates the event. Note: on February 23rd, 1942 at about 7:15 pm, shells began falling on Ellwood Oil Field west of Santa Barbara in what is today Goleta. At least 16 rounds (some reports say as many as 25) were fired on the oil facility over a period of twenty minutes by Japanese submarine I-17. The rounds were 140 mm (5.5 inches). The distinction is that the earlier attack was against an undefended civilian installation, while I-25 fired upon a fort that could defend itself.

|

| American soldiers examine the shell holes from the June 1942 attack. |

Besides sensing a soft target, the Japanese had another reason to return to the Oregon coast. That June 1942 Japanese attack was launched in retaliation for the Doolittle raid of the previous April. Sure, not much was accomplished by the I-25 shelling - but then, not much was accomplished by the Doolittle raid, either, beyond the loss of numerous and precious American bombers.

|

| Shell splinters are given out as souvenirs. |

However, the mission was a boost to Japanese morale just as the Doolittle raid had sparked American spirits. The submarine was not done after its June strike, either: it returned in September 1942 to up the ante and perhaps finally catch the Americans' attention.

|

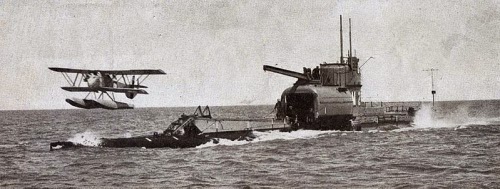

| Japanese submarine I-38, similar to I-25. |

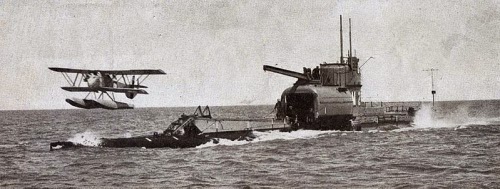

So, with two victorious campaigns along the Oregon coastline already under their belts, on 9 September the ship's crew prepared the ship's E14Y (Glen) floatplane, kept in a waterproof hangar attached to the conning tower. They unfolded its wings and prepared the engine. Chief Warrant Officer Nobuo Fujita and Petty Officer Shoji Okuda got in and took off via catapult.

|

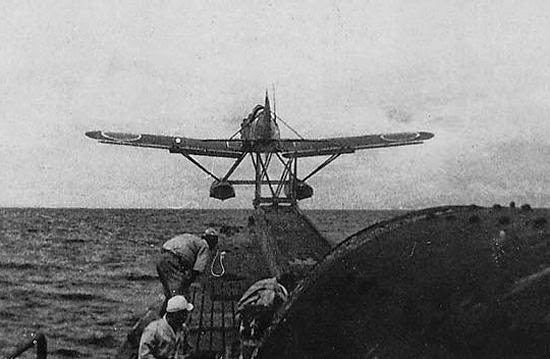

| A floatplane similar to Fujita's takes off. |

Warrant Officer Fujita flew the plane northeast and oriented himself with the Cape Blanco lighthouse, the westernmost point of land in Oregon. This wasn't important in terms of dropping the payload, but it was absolutely critical if the two men ever wanted to see Japan again.

|

| Cape Blanco lighthouse |

The two men flew over the coastal range unmolested. Their target was not a city or a military installation, but something the Japanese high command considered a higher priority target: a pine forest. The two successfully dropped two (apparently, though remains of only one were found) 168-pound firebombs over the forests in the hope of setting terrible forest fires. Then, they scooted back over the coast.

|

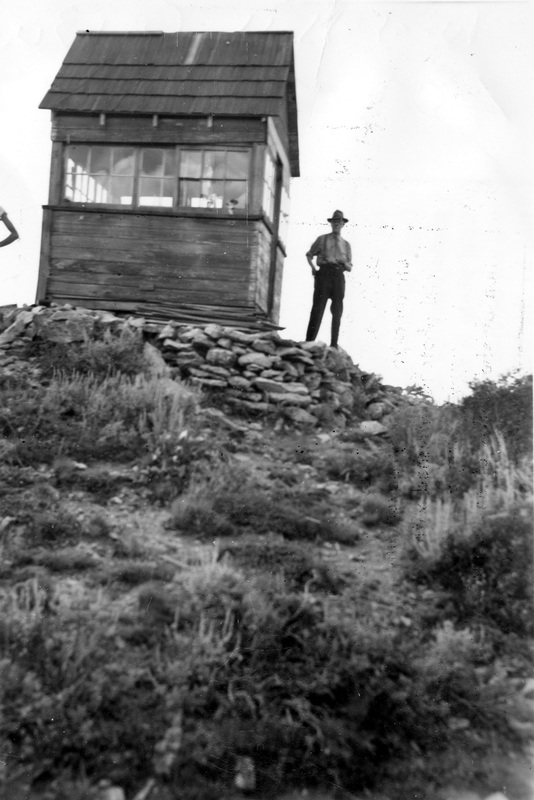

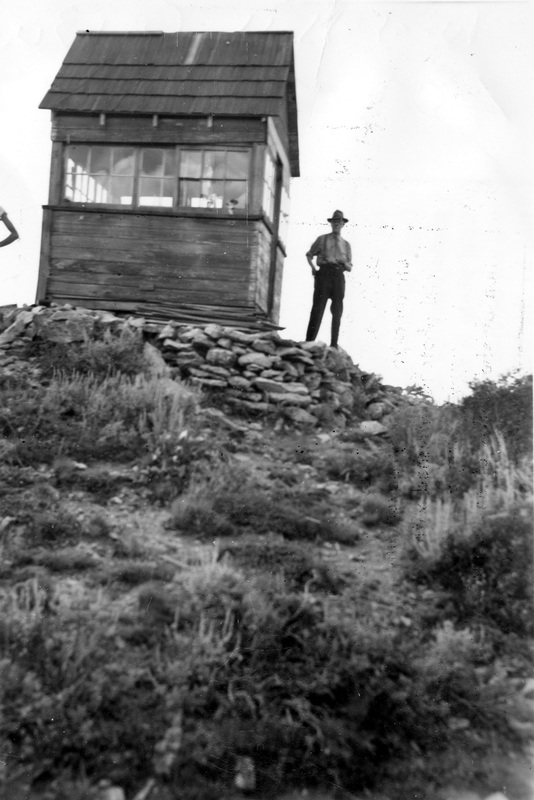

| The first lookout on this site was a D-6 cupola cabin erected in 1922. It had to be rebuilt after severe lightning damage in 1925. It was later replaced in 1948 by a 20' treated timber L-4 tower, which was removed in 1973. This is how the lookout site would have appeared in 1942. Nothing fancy, but it worked. |

In fact, unbeknownst to the Japanese, the Americans already had noticed what was going on. Posted in a fire lookout tower on Mount Emily in the Siskiyou National Forest, Howard “Razz” Gardner spotted and reported the incoming “Glen.” Razz could not see the actual bombing in the morning gloom, but the smoke plume soon became apparent. Razz immediately reported the fire to his dispatch office and was then instructed to hike to the fire and do whatever he could to suppress it, until USFS Fire Lookout Keith V. Johnson, from the nearby Bear Wallow Lookout Tower, could arrive to assist. As the only two men in the area, they were the nation's defensive force standing between the fire and the fort. Fortunately, the fire burned itself out. The attack “could have caused serious fires had not the forest been wet with unseasonable rain and fog,” writes William H. Langenberg in Aviation History magazine. Otherwise, the fire conceivably could have burned all the way to Fort Stevens - their nemesis. Perhaps the Americans would have noticed

that.

|

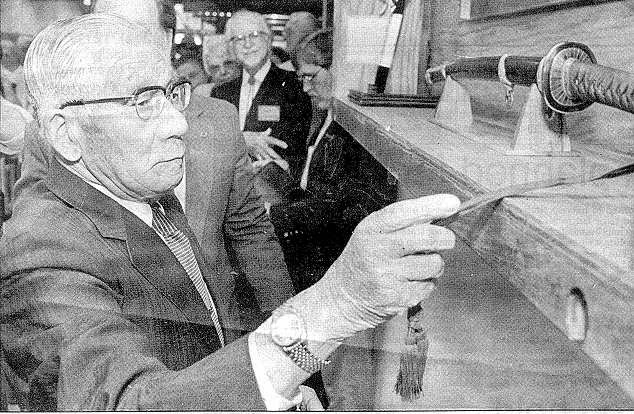

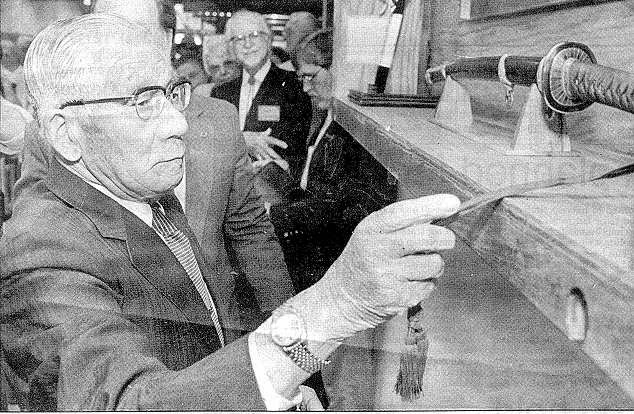

| Nobuo Fujita presents his family's Samurai sword to Brookings, Oregon in 1962 |

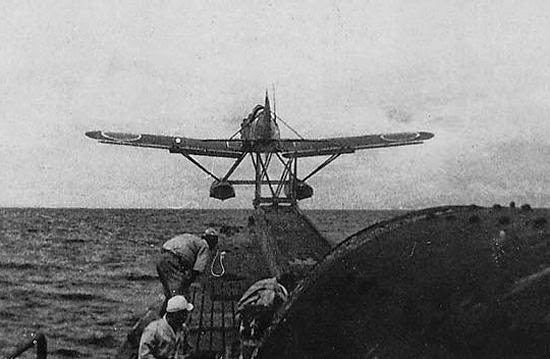

Fujita, oblivious to the tepid American reaction, calmly flew back to the submarine's location but had difficulty finding it at first. Not locating it, of course, meant certain death or capture -- and death was preferable to capture. Fujita eventually found the sub, though, and landed in the water nearby on the plane's floats.

|

| A typical launch of a "Glen." |

The submarine's crew members quickly retrieved and stowed the plane and the ship dived to 250 feet before any Americans arrived to see it. There, they stayed quietly -- listening to American depth charges dropped apparently at random -- as the United States Navy searched frantically for them. Once again - mission accomplished, another brilliant success for the Imperial Japanese Navy, especially since they could not know that the fires quickly went out due to the dampness. Commander Tagami radioed home about the heroic event, and the IJN could not keep the news to itself. The main front-page article in the Asahi newspaper's evening edition on Sept. 17, 1942, carried a banner headline:

''Incendiary Bomb Dropped on Oregon State. First Air Raid on Mainland America. Big Shock to Americans.''

|

| Nobuo Fujita places his sword in its ceremonial location at the Brookings library. |

Fujita, though, was not done. The sub still had four bombs for the floatplane, enough for two more missions. Captain Tagami authorized a second attack on 29 September 1942. The I-25 surfaced about 50 miles from Cape Blanco during the night and launched the seaplane again. There at least now was evidence that the Americans had at least noticed the earlier attacks - the entire coastline was dark, blacked out in fear - fear of Fujita and his two tiny bombs.

|

| Nobuo Fujita passed away in October 1997. |

The two men flew east past the lighthouse for about half an hour, then dropped their bombs perhaps 100 miles inland. Fujita saw the bombs explode, then headed back out to sea. He cut his engines at the coastline, gliding down to avoid being spotted again. Once again, he found the I-25 after some difficulty, locating it via an oil slick left by the slightly damaged sub, which now had been operating continuously off the coast for weeks and soon would need to return to Japan for maintenance.

|

| Nobuo Fujita as he appeared during the war, in a sketch made from an official Imperial Japanese photograph. He was viewed as a hero by the Japanese after the attacks, and it is hard to argue with that - they were incredibly dangerous, and it is a wonder that he found the I-25 again after both missions. |

The I-25 remained off the coast until 11 October without launching any more missions and then headed home to Yokosuka. Fujita was hailed as a hero, but he had accomplished nothing but a propaganda victory. The forest fires were minimal and the IJN plan proven to be mistaken in its planned effects. I-25 was sunk less than a year later by USS Patterson (DD-392) off the New Hebrides Islands on September 3, 1943. Fujita's crewman, Petty Officer Okuda, was later killed in the South Pacific.

|

| Fujita and his plane. |

After the war, Fujita started a hardware store in Ibaraki Prefecture, near Tokyo, but it eventually went bankrupt. He later worked at a company making wire. Executive officer Tatsuo Tsukudo, second in command of I-25, also survived the war and retired from the IJN as a vice admiral. In 1962, Nobuo Fujita, overcome with remorse at the attacks against what had become a staunch ally of Japan, visited the town of Brookings near the scene of the attacks. He was fearful that the Americans would jeer him, so he brought along a ceremonial Samurai sword that had been in his family for generations with which to commit ritual Hari Kiri should events warrant.

|

| The Brookings trailhead to the bombsite at Mt. Emily. |

Instead, the Americans were very kind and forgave Fujita. They became fast friends, with Fujita donating his sword to the town as some minor form of recompense, planting a ceremonial tree, and engaging in various other activities with the town. He even contributed books about Japan to the local library, where his sword now resides in a place of honor.

2020

Neat story. Thanks for publishing.

ReplyDelete