Start of the Reconquest of Europe

|

| American paratroopers about to drop on Normandy early on June 6, 1944. They were the first ones back in France, while it was still dark. |

The story of D-Day, June 6th, 1944, is so well known it scarcely requires re-telling. I'll go through the highlights briefly, with a few odd little-known facts here and there to keep anyone reading from getting too bored.

The Western Allies had been engaged in a "peripheral strategy" against German-occupied Europe for two years at the time of D-Day, but it had been only marginally successful.

North Africa had been conquered, but that was a sideshow and everyone knew it. Italy was a slow, endless grind that wasn't getting any easier.

|

| German soldiers in Normandy. Probably SS - they were always required to wear full camouflage. |

Pre-Invasion Strategy

Italy was proving extremely tough to reclaim and, quite frankly, more trouble than it was worth in military terms. |

| German soldiers in Normandy. 1944 (Federal archive). |

The only positive news that the public ever received about the Italian campaign was the capture of Rome a couple of days before D-Day. Otherwise, it was just a sequence of hard-fought battles and casualty lists.

|

| US Army M4 Sherman tanks and other equipment loaded in an LCT, ready for the invasion of France, circa late May or early Jun 1944. This is how wars are won. |

The war was going to last a long time if the Allies were going to just rely on their forces in Italy and the Russian front. The Allies were bogged down by excellent delaying tactics on the Italian peninsula, and the Soviets were grinding it out but still faced strong German forces deep inside their territory.

The time had come to launch an invasion on the short road to Berlin in order to string out the German defenders, and Normandy was chosen as the best spot.

|

| The famous shot of the D-Day landings, with barrage balloons and endless convoys of tanks and supplies |

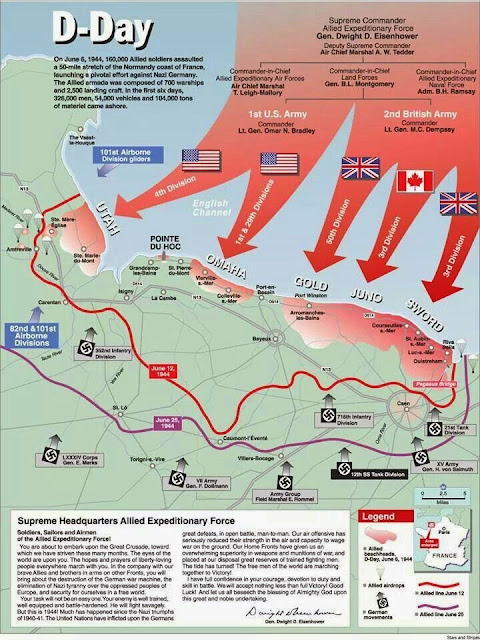

Why Normandy? Because that was within fighter range from British airfields. It also was the slightly less obvious of the two main possibilities for invasion, the other being the Pas de Calais (also within fighter range and thus the only other realistic place). It was the Allied, not the Axis, capabilities that determined the destination. Among the many Allies supporting the invasion were the Tuskegee Airmen pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group, who painted the tails of their P-47 Thunderbolts red. This gave them the nickname "Red Tails."

In war, tiny advantages matter. The Allies knew that the Germans would be waiting for them at the Pas de Calais because it was so obvious and the shortest route across the English Channel. On a clear day, you could see the French coast from Dover 20 miles across the Channel from England to the Pas de Calais. Everybody knew that was the "short route" across the water and on to Berlin. The Germans themselves would be planning to use a similar tactic as the Allies did - they were planning on landing on the Southern Coast of England, not take the short route to Dover. But the Germans seemed to lose a lot of strategic sense in 1944, both in the West and in the East.

|

| Another German coastal gun in Normandy. Many of the German emplacement remain, though the guns themselves are long gone. |

There were multiple advantages for the Germans if the Allies, in fact, had chosen the Pas de Calais for their invasion. It was closer for reinforcement and re-supply from German factories and industrial centers such as the Ruhr.

|

| Paratroopers getting ready (colorized). |

There also were major forces nearby in every direction. Since the success of the invasion depended upon building up forces in the beachhead faster than the enemy, the quick availability of reinforcement was vital, if not decisive.

On balance, for the Allies the balance of considerations favored keeping German supplies attenuated, making the more distant (from German factories and reinforcements) invasion location more attractive even though it was a bit further away for them, too.

|

| Troops and crewmen aboard a Coast Guard-manned LCVP as it approaches a Normandy beach on “D-Day.” (June 6, 1944). Note the nice, big flag. |

So, the Americans did their best to convince the Germans that the Pas de Calais was their destination while focusing on Normandy all along. This included creating an artificial army across the Channel from the Pas de Calais, sending radio signals from that location (where there actually were very few forces), and pretending that General George S. Patton was in command of the "invasion forces" there.

The Grand Deception Campaign

The deception campaign by the Allies surrounding D-Day is part of the lore of the operation and fun for some patriotic people to reflect in self-satisfied fashion on how the Allies "pulled a fast one" on the "dumb Germans." This fits into a general framework that the Germans were decadent from four years of occupation duty in France and too stupid to make realistic appreciations of the developing situation, that they were confused and bewildered by all intricate Allied feints.

It is nice to think that not only are you stronger in a material sense than your opponent but more clever as well and thus superior in a moral sense. The Japanese tried similar wildly complicated feints in the Pacific, for instance at Midway, which if they had any effect at all only hurt themselves. The bottom line is that the Allied deceptions on the day of the D-Day invasion were almost all ineffective, though they at least did not hurt the overall operation like the complex Japanese maneuvers did.

|

| A soldier is seen writing the names of the deceased on canvas body bags following the D-Day invasion, which took place on June 6, 1944. This would have been censored. |

There were several specific and separate deception strategies under the general rubric of Operation Bodyguard, the name for the overall deception strategy:

Operation Taxable - simulated an invasion force (using small boats, towed barrage balloons, etc.) approaching Cap d'Antifer;

Operation Glimmer - simulated an invasion force approaching Pas de Calais;

Operation Big Drum - operated radar-jamming equipment off the French coast;

Operation Titanic - an airborne deception strategy.

Have you ever heard these names? Unless you are a top historian of the invasion, probably not. That's because they were almost all completely ineffective and unnecessary, thus not worth emphasizing by the victors. That's how official history works. Nice efforts, good concepts - and useless.

Operation Taxable - simulated an invasion force (using small boats, towed barrage balloons, etc.) approaching Cap d'Antifer;

Operation Glimmer - simulated an invasion force approaching Pas de Calais;

Operation Big Drum - operated radar-jamming equipment off the French coast;

Operation Titanic - an airborne deception strategy.

Have you ever heard these names? Unless you are a top historian of the invasion, probably not. That's because they were almost all completely ineffective and unnecessary, thus not worth emphasizing by the victors. That's how official history works. Nice efforts, good concepts - and useless.

|

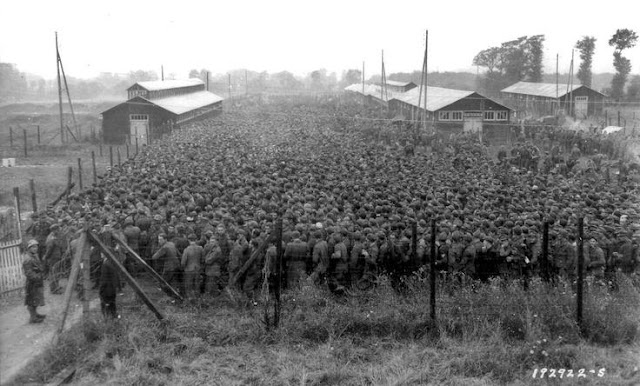

| German prisoners of war captured after the D-Day landings in Normandy are guarded by U.S. troops at a camp in Nonant-le-Pin, France, on August 21, 1944. |

Overall, the Germans did not fall for the deceptions - but then, they really did not react too much at all on June 6, even to the actual invasion itself. To the extent the deception operations confused and distracted a few random Germans on the coast (some Allied bomber feints were attacked by the Germans - but those Axis units would not have been used in Normandy anyway), they were probably worthwhile.

Their true benefit was that they made the Allied decision-makers more comfortable in their tough choices as "having done everything possible" whilst sending men to their deaths. The deception operations also may have comforted some soldiers approaching the French Coast who saw the operations headed in the other direction and concluded that the Germans were "looking the other way."

However, the bottom line is that the elaborate deception strategies did not materially contribute to victory. In fact, in an attempt to justify the operations and prove their wisdom, post-war historians scoured the record for evidence that they were effective. They found very little. The overwhelming Allied naval and air force armadas covering the actual invasion beaches and the troops holding rifles staggering through the waves - they ensured victory. It is a lesson worth remembering.

|

| A German 40.6cm (16-inch) coastal gun. The emplacement is still there and looks the same. The gun and German sentry - gone. |

Pre-Invasion German Preparation

Preparation is everything in war, as it is in life. While semi-obsessed with the Pas de Calais route, the Germans hadn't neglected Normandy. Far from it. Hitler half-expected the invasion to take place there, saying that his "intuition" told him it was the destination (his "intuition" may have been aided by spy reports he did not wish to discuss). General Erwin Rommel was convinced that he had done everything possible to defend Normandy, and perhaps he was correct given the resources available to him. However, Hitler kept the Normandy coast relatively weakly defended, counting on a Panzer riposte to take care of matters if the time came. Rommel also appears to have been strangely over-confident about the strength of his fairly useless efforts there.

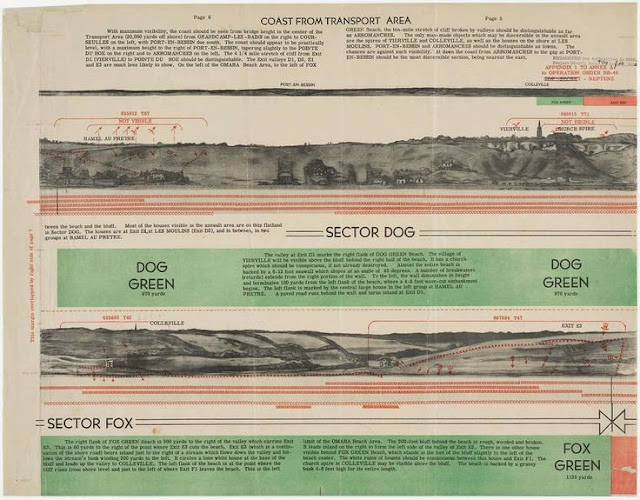

The Germans had laid mines everywhere in Normandy - literally millions of mines, some 4 million by the beginning of May 1944, and some of which are undoubtedly still there, buried deep beneath the sand. They built large coastal batteries, taking the guns from fixed defenses on the Siegfried Line and in East Prussia, and set up large beach obstacles in the surf. Normandy was not, however, as well defended as the Pas de Calais by troops and mobile forces because, as mentioned earlier, it was further from Germany, and it was considered that there would be more time to respond to an invasion there.

|

| Numerous German U-boats were at sea on 6 June 1944, but they were dispersed around the globe. Only a few were near the invasion beaches. |

That was true, but once the enemy was safely ashore and rapidly being reinforced, time to respond didn't matter much when you didn't have much to respond with. The Germans should have been mindful of their own experience at Crete in 1941 when their continual reinforcement from the mainland was the decisive factor. However, their strategic thinking in 1944 both in the East and the West was quite shaky, perhaps because Hitler had dismissed so many realistic top Generals by then and the remainder either were loyal Party members who could not even contemplate defeat or were opposed to the war entirely and not inclined to help the German war effort.

|

| Rommel with his chief of staff, Lieutenant-General Dr. Hans Speidel. Speidel went on to become a major figure in the post-war German Army (one of those generals who you couldn't take their picture). |

Rommel's Chief of Staff, Hans Speidel, is a key figure in this regard. Speidel soon after was involved in the 20 July 1944 plot against Hitler and was arrested by the Gestapo. Speidel is a murky figure to whom some ascribe pro-Allied motives, and it is known that he disobeyed some direct orders (such as an order to bomb Paris). Speidel was the man on the spot on D-Day (Rommel was on holiday back in Germany), and perhaps made some tactical decisions that covertly aided the Allied invasion. Let's just say that his heart was not completely vested in a German victory. How far that extended and what effect it may have had is an open question. Completely rehabilitated after the war, Speidel became a full General in NATO.

|

| Canadians disembarking on Juno Beach. They landed in between the two British sectors. |

The Invasion: Lodgement Phase

The invasion began on June 5, when ships from distant ports left their harbors with the intention of being at the Normandy beaches at first light the following day. Paratroopers from both the US and British armies embarked on gliders and transports and prepared to be flown inland to targets behind the beaches.The Germans were astonished because the weather had been poor and Allied security had been tight. The massive number of ships that suddenly appeared offshore also was a big surprise. The reaction was ragged and spotty. However, some of the big German coastal guns did get off a few rounds.

In the British sector, for instance, Operation Deadstick went into gear. This was the seizure of key bridges just behind the beaches to give the invading forces time to consolidate before heavy German tanks and troop reinforcements could respond. Troops from the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, the Royal Engineers, and the Glider Pilot Regiment - 181 men - were packed into six Horsa gliders in Dorset, in south-west England. Tug planes towed their aircraft towards the skies above Normandy, then released.

|

| This is one of the Horsa Gliders landed near the Pegasus Bridge. This picture makes it look isolated, but the photographer was standing next to another glider. |

Five of the gliders landed as close as 50 yards from the bridge (the sixth was seven miles off). The bridge was taken within ten minutes with only two casualties. They also secured another nearby bridge a few hundred yards to the East. It was the first major success of D-Day, preventing early German reinforcements from attacking the landing beaches.

At 00:16 on June 6, five of the gliders landed close to Pegasus bridge on the Caen canal - 50 yards away in one case, an epic feat of navigating in the dark - and a sixth landed close to a second crossing. Pegasus Bridge, a nothing little bridge, was captured within 10 minutes with the loss of two men from the Allied forces - the first to be killed under enemy fire in the D-Day invasion. Paratroopers also landed at many other places, though rarely with such precision.

|

| This shows nicely that the immediate objective was not to the east, but in the west - Cherbourg, a badly needed, isolated deep-water port that had to be taken as quickly as possible. |

At first light, things revved up: the first wave of troops had to get ashore for everything else to follow. The morning was stormy, but vessels already were in motion from some of the more distant embarkation points and paratroopers were being dropped. Eisenhower decided that calling everyone back at the last second would be worse than simply following through no matter the deleterious effects of the overcast day even if it got worse. The Germans were slightly relaxed because of the weather.

|

| A German telegram on 7 June 1944 setting forth the state of play. It is curiously general for the second day of an invasion: "Since early yesterday morning, there has been an enemy attack...." |

The Germans quickly brought forward the elite 1 SS Panzer Corps commanded by Hitler crony Sepp Dietrich:

- 21st Panzer Division;

- Panzer Lehr;

- 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend ("Hitler Youth").

The bottom line was that the Germans stopped the British cold, including a legendary stand in a single Tiger by Michael Wittmann at Villers-Bocage, a key road junction southwest of Caen, on June 13. In less than 15 minutes, he destroyed 13–14 British tanks, two anti-tank guns, and 13–15 transport vehicles. His actions and follow-up by his Heavy SS-Panzer Battalion 101 forced an immediate British retreat. In plain language, Wittman, a veteran of the Eastern Front including the Battle of Kursk, lit the British up and gave them a good spanking.

|

| Canadians study a German model of the beaches after capturing a German command post. Rommel was probably looking at this only days before. |

The Americans, on the other hand, had more difficulty getting ashore (because of Rommel's minefields and other precautions, particularly on Omaha Beach toward the center of the entire invasion). Once ashore, though, the Americans were able to quickly fan out over subsequent hours, days, and weeks (because re-supply from Germany and reinforcement was more difficult further west).

|

| General Omar Bradley was known as a "soldier's general." This picture illustrates why. He is going ashore with Admiral Alan Kirk on D-Day evening. |

A key objective on the American side of the invasion beaches was Pointe du Hoc. It split the US sector in half between Utah and Omaha Beaches and was the highest point in the area (100 feet or 33 meters). The Germans had fortified it with big guns that could have fired down on the GIs storming ashore. The 2nd Ranger Battalion, led by Lt. Col. James Earl Rudder, took this position while sustaining only 15 casualties. After that, the Germans had little chance of stopping the GIs storming ashore.

|

| Plan for the assault on Pointe du Hoc on 6 June 1944. |

The Americans took the first important post-D-Day target, the port of Cherbourg, after two full weeks of hard fighting. President Ronald Reagan gave a memorable 40th Anniversary speech there on 6 June 1984.

|

| Gellhorn was a war correspondent who made sure she was always out in the middle of the action. Gellhorn was the only woman who landed in Normandy on D-Day. |

Cherbourg had a deep-water harbor and was vital for serious re-supply and reinforcement. It was the single most important strategic objective of the invasion. In fact, if it was not taken, the Allied troops would be ripe for a panzer counterstroke, especially if - as actually happened - the weather turned bad and interfered with supplies to the beaches.

However, it took precious time to take Cherbourg. The Germans resisted furiously, and the city had very strong defenses. Cherbourg is not that far from Utah Beach, so the fact that it took so long to fall is proof that the Germans fought hard.

The Germans in Cherbourg were fighting like madmen and Hitler was all over the commanding officer to fight to the death, naming it his first "fortress" on the western front. However, the Germans there could not be resupplied once the Allies closed the roads from inland, so the German surrender was inevitable.

When the end became obvious, the German commander asked the Americans to use artillery at point-blank range to blow open the city gate before he surrendered so that his obeyance of the order to hold out as long as he could not be called into question by his countrymen.

The Americans were aided by Code Talkers who eliminated the need for time-consuming message encryption/decryption and made their troop movements more agile. The British, however, remained bogged down before Caen for weeks and had no major ports in their sector to capture.

The British, in their defense, faced the fiercest and most determined opposition once ashore. The Germans knew that if the British broke through to the East through Caen, the entire Normandy Peninsula (and France as a whole) would become quickly isolated and indefensible.

|

| A German soldier, probably SS and perhaps Hitlerjugend, in Normandy in June or July 1944 (Reich, Federal Archive, colorized). |

In that case, a general withdrawal would be required, with all forces already there having to surrender. Thus, it was a critical spot.

The Germans, perhaps due to lack of confidence or raw fear, defended against the British frontally rather than trying a Manstein-style riposte against overextended flanks which might have had more success. It probably was the wisest short-term course given their lack of command of the air which made road movements dangerous and costly, but it doomed the Germans to eventual defeat as the Allies steadily built up their forces to overwhelming proportions. The British, however, never broke through the German block despite intense efforts, it was the Americans who finally broke out to the south.

The German forces in place for the defense of the Pas de Calais further north also were relatively close by to the British sector. They could directly meet the British head-on faster than they could loop around the British and then turn north to confront the Americans or try a more intricate maneuver against the British.

There was no subtlety, and too much road movement was both dangerous due to air attack and taxed scarce fuel supplies.

The heavy tanks of the 12th SS Panzer Division were quickly moved into good defensive positions to prevent a British breakout. They came under constant British attack but were ordered to stand fast.

Stand fast they did, at the cost of thousands of their soldiers. The leaders were hardened veterans of the Russian Front, but inside many of the tanks were boys who had grown up under the Third Reich and knew no other way.

|

| PzKpfw. V “Panther” of 12.SS Panzer Division “Hitlerjugend” in Normandy, 1944. While the Panther was considered a medium tank, in fact, it was heavier than anything the Allies had in France. |

The Americans, paradoxically, were heading west away from Germany toward Cherbourg, not east toward German troop concentrations. As long as the British served as a blocking force for counter-attacks from the East, the Americans had a free hand in the West against light opposition. The Germans thought they were blocking the British, but in fact, the British were blocking the Germans.

|

| Among Hitler's priorities were protecting the V-1 launching sites a little further north along the French coast. |

There was one other vital reason for keeping the major German forces along the coast to the north of Normandy, which may have been the most important of all. It isn't mentioned very much in official histories, but Hitler himself alluded to it obliquely in his Directive No. 51 of November 3, 1943:

Everything indicates that the enemy will launch an offensive against the Western Forces of Europe, at the latest in the spring, perhaps even earlier. I can therefore no longer take responsibility for further weakening the west, in favor of other theaters of war. I have therefore decided to reinforce its defenses, particularly those places from which long-range bombardment of England will begin.Directive 51 led directly to the appointment of Erwin Rommel, who was famous but ultimately had a very small impact against the invasion, and that is what everybody mentions. The part most people miss in the directive is the very last clause in the quoted selection: "particularly those places from which long-range bombardment of England will begin." Hitler knew something very few other people knew: that the V-1 launching sites were being built around the Pas de Calais area and could not be moved elsewhere due to range limitations. He had bet his chips on those advanced weapons winning the war or at least serving as a tool to keep demoralized troops fighting. Huge expenditures had been made, V-1s were just becoming ready to use, and they were terrifying new weapons with incalculable effects on enemy morale. Losing those sites was unthinkable. That was why he kept his forces to the north, not because of any Allied deceptions.

Allied Command of the Air

German troop movement was severely constrained by Allied air attacks, so troop movement proximity to their destination was all-important. They lost a fraction of their troops for every mile they traveled. They would have lost a large fraction of their forces from air attack if they tried to skirt the British who were nearby and traveled much further over open roads to confront the Americans. The Americans had complete command of the French air that Spring. Besides, the Germans had enough problems just containing the British. In a way, the situation was quite similar to the roles that the British and the Americans played during the invasion of Sicily when the British took the quick route to Messina and the Germans frantically and fanatically blocked them, while the Americans had a free hand in the western half of the island and occupied huge swathes of territory while the British were stalled on the east coast.

The French partisans also were stirred up and doing things to slow down the German troop movements (and some tragic massacres committed by the frustrated Germans resulted, such as at Oradour-sur-Glane to the south). The partisans greatly helped the Allied commandos who parachuted in ahead of the invasion and harassed the German attempts at reinforcement.

As it was, there was no way around it: German troops had to use the roads and railways to maneuver and were decimated by daylight air raids, including General Erwin Rommel being strafed and nearly killed in his staff car on July 17th. Every mile moved along the roads was a huge risk for the Germans, but their supplies didn't come that way anyway. They moved almost all of their supplies by rail, and distance there also was a major factor in how quickly supplies arrived due to incessant Allied attacks on the rails.

The Germans had to spread out forces across France to keep the indispensable railroads running: Flak crews, work gangs, sentries to guard against partisan attacks on rails, bridges, and tunnels. The Americans would blow up railway bridges during the day and the Germans would repair them at night. Canals would be drained during daylight and refilled after dark. Everything possible was done to keep transportation operational.

|

| These prisoners from the 12th SS Hitlerjugend Division were captured during the early portion of the battle for Caen. |

The same reasons that would have made the Pas de Calais more convenient for the Germans to defend also made engaging the nearby British, and not the more distant Americans out on the peninsula, more feasible for the Germans. There was less open road and railway to travel over, less infrastructure that had to be repaired after the bombardment, and fewer remote installations to guard against sabotage. Nearby forces could be concentrated on the direct road to Paris.

While the Allied Navy may be said to have won the battle of Normandy, the Luftwaffe also may be said to have lost it. This was a well-known belief within the Wehrmacht and the source of much bitterness by the rank and file.

Thus, for these reasons the Germans had their best troops facing the British on the east end of the perimeter while the Americans faced lesser opposition to the west. The Americans, though, did not have it easy, as the beaches in their sector were heavily defended from the outset by relatively good troops - the Germans did realize to some extent the factors outlined above and thus realized that winning at the beaches was all the more important further west in Normandy. Re-supply to the Germans farther west being limited, the going gradually got easier for the Americans. It also is the reason they ultimately were the ones who managed to break out of the bridgehead while the British remained stalled throughout.

The paratroopers also interrupted immediate reinforcements. The invasion began with paratrooper drops several miles inland while it was dark. These landings were often off-target with the troops widely dispersed, and there were casualties from crashed gliders. This development, though, was actually a lucky break. The paratroopers appeared in the dark seemingly everywhere and caused chaos in the German rear, killing any Germans they saw and terrorizing the rest. They may have been more effective in helping the Invasion doing that than if they had all banded together and tried to seize objectives and hold them. The defeat at Arnhem in September showed how difficult that could be.

|

| Luftwaffe FLAK crew in France, just outside Paris between there and Rouen. They were in a position to protect vital and vulnerable supply lines across France |

Post-Lodgement Strategy

Once the lodgement area had been secured by nightfall of June 6, the battle was won. Naval guns from the battleships and cruisers parked offshore could take care of any determined counter-attacks - the Allied had a lot of experience with this from Sicily, Salerno, and Anzio. Given a secure perimeter, the Allies could re-supply faster by sea than the Germans could by land, given the Allied air forces' overwhelming superiority over the Luftwaffe. The beachheads linked up within days, forming one huge invasion bridgehead. That took a lot of the strain off the defenders. |

| Waffen SS near Utah Beach. The SS fought determinedly and managed to seal off the bridgehead, but they did not have nearly enough numbers to throw the invaders back into the sea. |

Once settled in, the Allies gradually expanded their beachhead while they built up the overwhelming superiority of material and troops. The going was difficult through immense hedgerows that had been growing since the Middle Ages, but those same hedgerows also served as nice defensive barriers against panzer counter-attacks. The Allies fell behind projections set before the invasion for phase lines of advance but made up for that after the breakout from Avranches in the south of the Normandy peninsula on August 31st.

When the time was right and they had overwhelming force, the Allies struck. The Americans broke out in Operation Avalanche to the south, away from the largest German concentrations to directly to the East, just as General Manstein in 1942 (Unternehmen Trappenjagd) had broken through the southern part of the enemy lines, away from their main concentrations, in the Crimea. There was nothing really new about what was going on, it was simply a brilliant execution.

Once the Americans established their breakout, France fell completely within a month. The Normandy landings were aided by another invasion in the South of France, Operation Dragoon, on August 15 that was hugely important but has been pretty much forgotten.

|

| 6th June 1944: Allied troops exiting a landing craft in trucks on a beachhead during the D-Day landings in Normandy, France. |

Incidentally, the name "D-Day" has no special significance and is not short for anything. It was standard practice to code major operations in that way, the "D" comes from "Day" just for emphasis that it was the day for this major operation. It could have been anything and was a meaningless rhetorical flourish.

The Normandy landings succeeded, but there was still a lot of fighting. The Germans were beaten, but not defeated. The public in the Western Allies mistakenly thought the war, therefore, was won and that the boys would be home by Christmas. They were wrong. Rocket attacks, a German counteroffensive, and the discovery of the gas chambers were still to come. A long, cold, bitter winter awaited.

Below are additional photographs from all phases of the Invasion.

Below are additional photographs from all phases of the Invasion.

Additional Shots

|

| 6th June 1944: Allied troops ride in an open truck while a landing craft sits on the shore in the background on a beachhead in Normandy, France, World War II, D-Day. |

Top D-Day movies:

- The Longest Day (1962) John Wayne, Henry Fonda, Sean Connery

- Saving Private Ryan (1998) Tom Hanks, Tom Sizemore

- The Big Red One (1980) Lee Marvin, Mark Hamill

- D-Day the Sixth of June (1956) Robert Taylor, Edmond O'Brien

- Band of Brothers (2001) Scott Grimes, Matthew Leitch

"The Longest Day" gives you absolutely the best overview of D-Day, with an iconic never-before-or-since helicopter shot of the invasion beaches, a rare look at the German side without them being simply caricatures, and perhaps the best cast in film history. On the other hand, the American characters do lean to the caricature side, which is the film's one huge failing. Yes, and John Wayne saves the day in a heroic fashion, what did you expect.

"Saving Private Ryan" gives a granular look at the big day, at a few men on a particular mission. Great, hyper-realistic action and Tom Hanks playing a perfect role put this in second place. However, great as the film is, it is wildly overrated for any number of reasons, including the somewhat maudlin/melodramatic interludes, the hokey set-up, and a bit too much razzle-dazzle including blood spurting out of shot Germans and such. Soldiers are usually grunts, and this film, while great, does not nearly capture the tedium and muddling-through that is an essential part of a real soldier's experience and the way actual battles are won. I know you love it and probably hate me for saying the least bit critical about this iconic treasure, but just accept that there are different viewpoints. Besides, I did put it second, which is a common spot by reviewers of D-Day films.

"The Big Red One" is amazing because it follows the rugged First Infantry Division and places the D-Day invasion in some sort of personal context. Normandy wasn't the first invasion for the Big Red One (the division's nickname), but I'll let you watch the film without further ado. Oh, and one further thing: Lee Marvin.

|

| Edmond O'Brien may be the most underrated actor in Hollywood history. He did an outstanding job as a victim of battle fatigue, a very sensitive topic at the time, in "D-Day The Sixth of June." |

My dark horse selection is 'D-Day The Sixth of June." I can pretty much guarantee you that you will not find this film on any other 'best' list. It is a bit of a chick flick that gives short shrift to the actual landing, and I know you probably won't like that aspect. However - and this is a big "however" - it has some amazing performances and gives a completely different perspective on the invasion, a human dimension in context, that is absolutely essential to understanding what real people (and not heroic caricatures like the John Wayne character mentioned above) went through. The best scene is "small": the Edmond O'Brien character, playing a wounded Canadian officer, describing what he went through during the failed Dieppe assault two years previously in very graphic terms. That one scene alone will stick with you and is worth watching the entire film, but the whole movie delivers.

"Band of Brothers" was a television mini-series, and it has the one huge advantage of going on and on and on, showing a lot of detail. It is a good production, not as iconic as the other films on this list and a bit melodramatic, but worth watching if you want to set aside the time.

|

| Aerial view of the invasion of Normandy. The Americans and British had complete domination of the sky, with some 11,000 aircraft to barely any at all of the Luftwaffe. |

|

| General Eisenhower giving an inspirational talk to paratroopers the day before the Invasion. |

|

| Soldiers wading ashore on D-Day. |

The story of D-Day includes the Home Fronts. Everybody was kept in suspense about the success or failure of the Invasion throughout the day. It was nerve-wracking, but the results turned out OK for the Allies.

Below is a good documentary of D-Day, with narration.

2022

|

| A sign outside Trinity Church, New York City, inviting worshippers to 'Come in and pray for Allied victory in the invasion of Normandy on D-Day, 6th June 1944. |

|

| A '2nd Invasion Extra' edition of the Worcester Telegram newspaper, published in Worcester, Massachusetts, reporting the Allied invasion of Normandy on D-Day, 6th June 1944. |

|

| A newspaper seller in London on D Day - the start of the Allied invasion of Europe. |

|

| An anxious crowd formed in Times Square, NYC, watching the zipper news feed for any news about the success of the invasion. |

|

| Ten weeks of operations compressed into one map. |

2022

Excellent. I read the whole thing. Well written, and very informative. But, I was dissapointed you did mention the Red Tails and their contributions to the effort. Reading histoy is my best hobby. Thank you,

ReplyDeleteNancy Stell

Not a bad suggestion at all. I don't know if I have any mentions of the Red Tails anywhere else yet, so I put one in this article. I'll probably do an article about the Tuskegee Airmen at some point, too. Thanks for reading and commenting!

Delete