A Pointless Waste of Life

|

| Iwo Jima after the battle. |

"Well, this will be easy. The Japanese will surrender Iwo Jima without a fight." – Admiral Chester W. Nimitz.

The Battle of Iwo Jima has seared itself into the American consciousness. Just as the defense of Stalingrad became iconic for the Soviet Union and the defeat of the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain became shorthand for a British victory in England, Iwo Jima for Americans stands for more than just the conquest of a remote island. In a visceral way, it summarizes the U.S. victory in the Pacific. Let's take a look at the battle, which resonates for three separate reasons: 1) the viciousness and savagery of the battle, 2) portents for the future, and 3) the iconic flag-raising at the end. Let's look at each in turn.

I know what you may be thinking - rah rah rah go USA! US Marine Corps all the way! And that's fine, the Marines deserve credit for what they went through on Iwo Jima. They suffered horribly. My point is not that they did anything wrong. The Marines acted heroically and the capture of Iwo Jima is a shining moment in their history and the history of the U.S. military.

My point instead is simply that the Marines shouldn't have had to invade Iwo Jima at all. Capturing it served no useful purpose and cost tens of thousands of lives for virtually no benefit whatsoever.

Operation Detachment

By late 1944, the U.S. offensive in the Pacific had resolved itself into two separate axes of advance. One, commanded by five-star Army General Douglas MacArthur, headed through the southwest Pacific toward New Guinea and ultimately the Philippines. The other, further to the north, headed west in an island-hopping manner toward islands closer to Japan. The main objectives included Saipan, Guam, and Tinian. This latter axis of advance was under the command of Fleet Admiral (effective 19 December 1944) Chester W. Nimitz (CINCPACFLT). This division was not ideal, and caused various issues along the way, particularly in the Philippines where the command was divided between MacArthur and Nimitz. However, the separate strategies employed by the two men were both successful in their own ways.

|

| A look at the landing plan for Iwo Jima. It involved lodgement in the center of the island and then quick capture of the three airfields on the flat part of the island. |

By June 1944, it had become clear that islands close to the Japanese mainland were coming within the grasp of the U.S. military. A quick glance at the map showed why Iwo Jima might be useful. It was fairly close to Japan - only three hours by air - and appeared to be a good staging area for the proposed invasion of Japan (Operation Downfall). However, Iwo Jima did not possess good harbors, making it useless for both the U.S. Army and the Navy. What it did possess, and the only thing that ultimately made the island useful at all were three small airfields. While not adequate for large-scale bombing operations, these airfields could be used as an emergency landing strip for bombers and for fighter coverage of the area. The flat nature of the island suggested that an invasion force could quickly occupy the airfields, the only thing worth having on the island, and then take its time completing the conquest of the more rugged terrain in the island's southwest tip.

|

| Admiral Spruance's fleet provided naval support throughout the battle for Iwo Jima. |

Japan assigned Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi to hold Iwo Jima. On the U.S. side, naval intelligence adjudged Iwo Jima, a flat, relatively featureless atoll with a large feature in its extreme southwest sector called Mount Suribachi, to be relatively easy to subdue. Kuribayashi, however, feverishly began consolidating the island's defenses. Based on previous U.S. island invasions, Kuribayashi organized a defense in depth which would focus on bunkers and caves rather than another defense of the beaches, a strategy which always had failed due to the overwhelming force of allied naval gunfire. Admiral Nimitz shared his intelligence service's optimism and figured that heavy bombing raids would shatter whatever resistance the Japanese could muster on Iwo Jima. After hundreds of tons of Allied bombs and thousands of rounds of heavy naval gunfire, Nimitz sent his fleet to invade the island on 19 February 1945.

|

| Approaching Iwo Jima in the first assault wave. |

Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher parked his Task Force 58 off Iwo Jima. Under the overall command of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, the hero of Midway, aboard cruiser U.S.S. Indianapolis, the first wave hit the beat at 08:59. This force of marines was under the command of Major General Harry Schmidt. Relations between the Marines and the fleet command were not particularly rosy, as Schmidt and his subordinates felt that the Navy was spending too little time bombarding invasion islands. While the landing itself was routine, moving inland was not because right behind the beaches of black volcanic ash were 15-foot (5 meters) dunes. Carrying heavy equipment, the marines had trouble struggling up the hill, but at least they didn't face any return fire. Everything was quiet - too quiet, as they say.

The Navy, meanwhile, noted that no Japanese were actually on the beach or directly behind it and figured they had been proven right about going with light with pre-landing bombardment. The problem with that thinking was that the Japanese never had intended to defend the beach. Everybody on the U.S. side figured that since the landings had been virtually unopposed, the remainder of the campaign would be trivial. This erroneous assumption was erased an hour after the landing, when, with the beaches packed with troops and equipment, the Japanese on Mount Suribachi suddenly opened up with everything they had. Navajo code-talkers with the 5th Marine Division sent 800 messages in the first 48 hours of the landing and played a very important role in the success of the landing.

The Japanese under Kuribayashi had hidden their artillery in caves high on the mountain behind steel doors. This had protected them from aerial surveillance, bombs, and naval gunfire. In effect, it didn't matter how long the U.S. Navy might have bombarded the island - they were aiming at the wrong areas. So, in a sense, the Navy was correct after all, though for the wrong reasons - might as well get things started as early as possible since additional shelling wouldn't make any difference anyway.

|

| A typical Japanese artillery location, which would have been concealed behind camouflaged steel doors until it was time to fire. |

The Japanese would open their steel doors, fire their artillery, and then immediately close the doors again. It was an effective strategy for the circumstances. The Marines on the beach, meanwhile, found that the slippery hill up toward the interior was unsuitable for their Amtracs, which got bogged down in the soft ash. There also was no cover on the black ash - the best you could do was try to dig yourself into the sand or shield yourself with a dead comrade. After an hour of this, the Naval Construction Battalion, the famous Seabees, used bulldozers to plow paths up the hills. This enabled the marines to advance past the beach and toward the airfields. By 11:30, they had reached the tip of the nearest airfield. After a "banzai" charge by 100 Japanese failed to dislodge them, the Marines kept this position through the night.

|

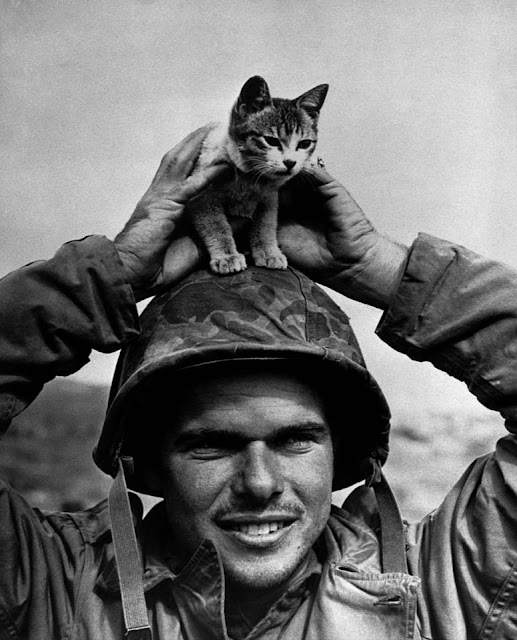

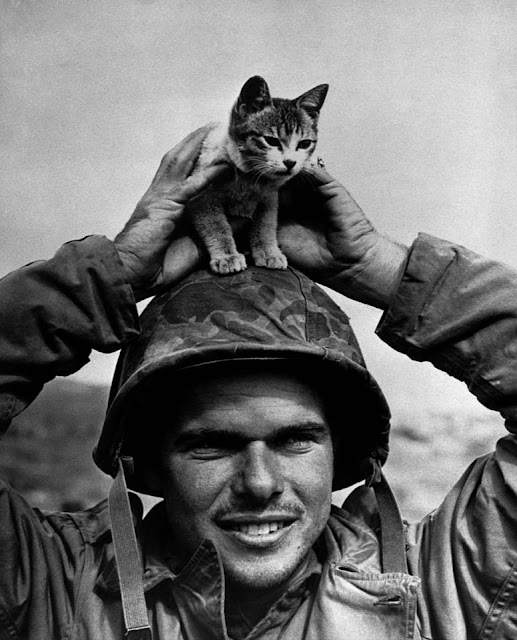

| Corporal Edward Burckhardt with a kitten that he said "captured him" at the base of Suribachi Yama as he came ashore with the Fifth Marine Division. February - March 1945 (Getty Images). |

To the south of the airfields, the Marines did achieve major success on the first day. Led by Col. Harry B. "Harry the Horse" Liversedge the 28th Marine Regiment, they crossed the island at its "neck" just northeast of Mount Suribachi. This cut the island in two and isolated the garrison on Mount Suribachi. To the north, the 25th Marine Regiment overcame resistance at a defensive feature known as the "Quarry." The unit's 3rd Battalion suffered 83.3% casualties before they secured the Quarry. By nightfall, there were 30,000 Marines on the island to face Kuribayashi's 21,060 troops.

The Japanese rightly surmised that the success of the invasion depended entirely on the fleet parked just offshore. On the third day of the invasion, 21 February 1945, they staged a kamikaze airstrike. In one of their last major successes of the war, Japanese planes sank escort carrier USS Bismarck Sea, damaged fleet carrier USS Saratoga, and damaged escort carrier USS Lunga Point, along with some smaller vessels. However, these losses did not impede the Marines and their fight on the island.

|

| U.S.S. Saratoga burning after a kamikaze strike on 21 February 1945 off Iwo Jima. |

After that, the Marines moved steadily inland. However, each step forward was dangerous, because the Japanese were hidden in caves and holes from which they sprang at the surprised Marines. The advance was a succession of ambushes and occasional counterattacks, with English-speaking Japanese pretending to call for assistance to set up more ambushes. Because the Japanese were dug in, flamethrowers became the weapon of choice on Iwo Jima. These included eight Sherman M4A3R3 flamethrower tanks (nicknamed "Zippo" and "Ronson" tanks after popular lighters).

|

| A Doberman Pinscher on Iwo Jima. |

The Marines occupied the flat area of Iwo Jima fairly rapidly. Occupying the airfields enabled the 15th Fighter Group to fly its P-51 Mustangs on the island by 6 March 1945. Airpower, however, was of limited use against Japanese troops hiding in bunkers and caves. These were ideal situations for the flamethrowers, which could either incinerate the hidden Japanese troops or suffocate them. Iwo Jima probably saw the most effective use of flamethrowers in the entire course of World War II.

|

| A soldier equipped with a flamethrower running on the beach. |

After effectively securing the flat portion of Iwo Jima (though large areas remained unsubdued), it was time to occupy the mountainous area to the southwest. On 23 February 1945, two rifle companies of the 2/28 Marines ascended the mountain. The Japanese remained in their bunkers and offered little resistance beyond a token firefight at the summit of Mount Suribachi. After briefly occupying the summit, these Marines descended and informed their commander that the way forward was clear. A reinforced patrol under the command of Lt. Harold Schrier then took an American flag to the summit, suggesting to some that resistance on the island was over - though it wasn't yet.

|

| Mount Suribachi. |

In fact, the Japanese remained dug in along the north shore of Iwo Jima. The terrain there was flatter than Mount Suribachi, but it was rocky and offered good defensive possibilities. It was here that Kuribayashi's preparations and the strategy paid off the most. The bulk of the remaining Japanese troops concentrated here. The Marines gave the features on this end of the island colorful nicknames to differentiate them: the Amphitheater and Turkey Knob, for instance. The main feature was Hill 382, which overlooked Airfield No. 2 in the middle of the island. Finally, frustrated, the 9th Marine Regiment made a surprise night attack without any preliminary bombardment. This achieved great success, catching many Japanese literally asleep.

The day after this night attack, the Japanese counterattacked. This attack on the evening of 8 March 1945 devolved into a typical Japanese banzai charge. As with all previous banzai charges, it failed with spectacular Japanese losses of 784 men. However, this futile charge was not without cost to the Marines, who lost 90 men killed and an additional 357 casualties.

The 3rd Marine Division also broke through to the coast in the north on 8 March, splitting the Japanese defense there. After this, the battle in the north turned into a mopping-up operation, and that portion of the island was deemed secured at 18:00 on 16 March 1945.

Final resistance on the island ended only after the Marines attacked General Kuribayashi himself in a ravine in the northwest tip of Iwo Jima. They dynamited Kuribayashi and his men in their command post on 21 March, then sealed the caves nearby on 24 March. The final major action took place on the night 25 March, when 300 Japanese launched a banzai attack near Airfield No. 2 in the center of the island. With this handled, the Marines declared the entire island of Iwo Jima secured on 26 March 1945. Only 216 Japanese of the original 20,000 allowed themselves to be taken prisoner.

|

| Some of the scarce Japanese soldiers taken prisoner on Iwo Jima. |

It is estimated that between 17,845 and 18375 Japanese soldiers perished on Iwo Jima. About 3000 Japanese remained alive on the island, uncaptured, for some time, hidden in their bunkers. Two men, Yamakage Kufuku and Matsudo Linsoki, did not surrender until 6 January 1949. On the American side, there were 6800 dead and about 20,000 other casualties. In other words, there were more U.S. casualties than the total number of Japanese defending the island. While these figures were dwarfed by later casualties on Okinawa during Operation Iceberg, Iwo Jima represented an unusually heavy loss of men for the U.S. military. Illustrating the savage nature of the battle, two Marines taken prisoner by the Japanese did not survive their captivity for very long.

|

| 4th Marine Division on the beach at Iwo Jima. |

Using 70 years of hindsight, in Operation Detachment the US Marines took a relatively unimportant island at a tremendous cost that resulted in little benefit. Iwo Jima could have been bypassed without hampering the war effort like so many other islands that were bypassed. Historians like to emphasize the 5,000 men that the Wehrmacht lost taking Crete and call that a mistaken campaign, but at least that island was strategically important within the Mediterranean. At the very least, taking Crete deprived the Royal Navy of very useful bases and protected the southeast flank of the Third Reich. Iwo Jima, on the other hand, cost more men, offered no strategic advantage, could not support a later invasion of Japan in any meaningful way, and had no useful harbors. At most, Iwo Jima offered a handy emergency airfield for stricken bombers returning from raids on Tokyo, but there were other options for them and it was a minor benefit to the war effort. As much as any Allied invasion of World War II, Operation Detachment was a product of overconfidence (see Admiral Nimitz' comment at the top of this article) and disregard of the toll of war.

|

| Marine Amtracs that were destroyed by artillery fire on Iwo Jima. |

Despite its relative proximity to Japan, the US Army Air Force did not base its bombers there. The main base was on Tinian, about three hours further away from Japan. Iwo Jima, with its lack of a harbor, was unsuitable for major air operations. All bombs were transported by ship, and atomic bombs were massive. Bringing them ashore at Iwo Jima was unfeasible. The USAAF kept its major bomber base on Tinian (others were on Guam and Saipan). The atomic bombers (Enola Gay and Bockscar) flew from Tinian, where the massive bombs could be off-loaded in a natural harbor and there were extensive airfields. Used only occasionally as an emergency landing field for crippled bombers, Iwo Jima offered virtually nothing to the United States.

In a desperate attempt to make the island useful for operations against the Japanese mainland, U.S. Navy Seabees attempted to make an artificial harbor at Iwo Jima's volcanic sand beach. To do this, they sank about 15 captured Japanese vessels that have become known as

the Iwo Jima ghost ships. This project was a complete failure and was quickly canceled. The island then returned to its lonely isolation, with burial parties taking care of the dead and occasional bombers damaged during raids on Japan landing on emergency airstrips.

Here is some brutal honesty about Iwo Jima. Operation Detachment offered a splendid example of brave soldiering on both sides and ultimately generated some iconic images. Every man who died there was a hero. Taking Iwo Jima did not, however, meaningfully influence the outcome of World War II. It was an unnecessary campaign that should not have been fought. You can say that this is "unpatriotic" or "it was a glorious victory and thus worth the cost," but 6,821 US GIs and around 18,000 Japanese soldiers died for this little display of heroism, with many others maimed. Yes, hindsight is perfect, but the utter uselessness of occupying Iwo Jima should have been plain at the time.

Foreshadowing the Future

Aside from the dramatic number of U.S. casualties which foreshadowed over twice as many on Okinawa (and an anticipated million if the Allies had to invade Japan), there were some things about Iwo Jima that offered a peek into the future of US combat operations. While not usually associated with World War II and sometimes having little impact on the Iwo Jima battle itself, these novel aspects of the Iwo Jima battle foreshadowed their widespread use in Korea and especially Vietnam.

|

| The first helicopter arrives on Iwo Jima, 23 March 1945. |

The first of these was the use of helicopters. The use of helicopters was rare on the Allied side during World War II. Igor Sikorsky had made great strides with his development of helicopters, and this included fitting them with pontoons for naval usage. The first Sikorsky R-4 helicopter landed on Iwo Jima on 23 March 1945, before the island officially had been subdued. It was greeted by a curious crowd of soldiers. This apparently was the first U.S. use of helicopters in a combat zone.

|

| The first Navy flight nurse on Iwo Jima (6 March 1945) and later Okinawa (6 April 1945) was ENS Jane Kendeigh, NC, USNR. She became a symbol for casualty evacuation and high-altitude nursing. (BUMED Archives). |

Another novel feature of Iwo Jima was the presence of female Navy nurses on the island. Ensign Jane Kendeigh arrived on the island on 6 March 1945. While the presence of female nurses in combat areas was not unheard of, Kendeigh became a symbol of the willingness of female nurses to enter modern combat zones. This would, of course, become a common practice in Korea and Vietnam, but it was still fairly unusual in 1945.

Extensive use of flamethrowers, including flamethrower tanks, was a hallmark of the Battle of Iwo Jima. The M2 Flamethrower exposed the operator to great danger from snipers and return fire, but it was an effective tool against enemies hiding in bunkers who refused to surrender. Tanks converted to flamethrowers were less effective on the rough terrain of the island, but one battalion commander called them the "best single weapon of the operation." Flamethrowers would remain in the US military arsenal through the Vietnam War.

The Flag on Mount Suribachi

As noted above, there were multiple flag-raisings on Iwo Jima. This led to some major misunderstandings over the years and some bitter feelings. Let's go through the myth and the reality.

|

| Charles W. Lindberg. He was United States Marine corporal on Iwo Jima. Lindberg helped secure Mount Suribachi - one of the few survivors of his patrol - and was present for the first flag raising at the summit. No pictures were taken of this actual flag-raising. A second flag-raising, long after the mountain had been secured, was photographed and became the iconic symbol of the battle. |

The myth is that the U.S. Marines had to viciously fight their way to the top of Mount Suribachi, and then battle to plant the flag there. This flag-raising was captured for posterity in the famous photograph that formed the basis for the Iwo Jima Memorial that was placed next to Arlington National Cemetery in 1954.

|

| Carrying the flag up Mount Suribachi for the initial flag-raising. |

The reality is a little different. The Marines did not have to fight their way up Mount Suribachi at all. In fact, they had a fairly easy time (relatively speaking) getting to the summit, and resistance there was quickly subdued. Nobody photographed the first flag-raising, though a Coast Guard cameraman captured shots immediately before and after the flag was put up using some abandoned Japanese pipe. Soldiers all across the island, especially on the beaches, could see the flag and knew that it was an unmistakable signal that the Americans were winning.

|

| First flag-raising on Mount Suribachi. |

This first flag went up just as US Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal landing on the beach. He was inspired by the sight and asked for it to be taken down and brought to him for safekeeping. Following orders, battalion commander Colonel Chandler Johnson sent Private Rene Gagnon up the mountain with a replacement flag. The Marines dutifully took the first flag down and replaced it with the second, larger flag, also using a piece of Japanese piping.

|

| Staff Sgt. Louis R. Lowery, a photographer with Leatherneck magazine, took this photograph of the first flag on Iwo Jima. Left to right: 1st Lt. Harold G. Schrier (kneeling next to radio operator), Pfc. Raymond Jacobs (radio operator), Sgt. Henry Hansen (soft cap, holding flagstaff), Pvt. Phil Ward (holding lower flagstaff), Platoon Sgt. Ernest Thomas (seated), PhM2c. John Bradley, USN (holding flagstaff above Ward), Pfc. James Michels (in the foreground with M1 carbine), and Lindberg (standing, extreme right). |

This second flag is the one that Marine photographer Joe Rosenthal took for the Associated Press. It also was filmed - in color - by Marine Sergeant Bill Genaust. This second flag flew until 14 March, when it was taken down due to the raising of another flag along the recently subdued north shore, at Kitano Point.

|

| The iconic second flag-raising on Mount Suribachi (Joe Rosenthal, AP). For Americans, at least, this is probably the most iconic image of World War II. It was recreated in the form of a statue in Washington, D.C., where it stands today. |

This sequence of events remained obscured for many years. This was partly the US Navy's doing because they realized the dramatic impact of Rosenthal's photograph and didn't want to do anything to detract from that effect. The Navy didn't even authorize the use of the photographs of the first flag raising until late 1947, and the first flag raising was not publicized. The Navy's preference for the second flag-raising extended to honor the men who had raised that flag - but not the first. This did not sit well with Charles W. Lindberg, a flamethrower soldier who had been wounded and evacuated from Iwo Jima on 1 March 1945 after participating in the first flag raising. After remaining bitter about it for many years, he began speaking out in the 1970s and raised public awareness of the first flag. Finally, the men who had raised that first flag - several of whom did not survive the battle - received their recognition.

2021

No comments:

Post a Comment